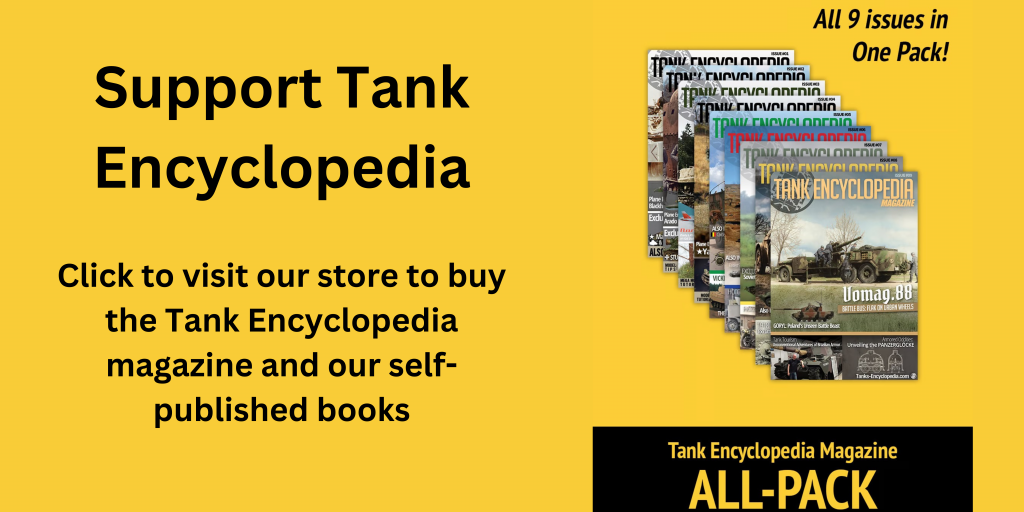

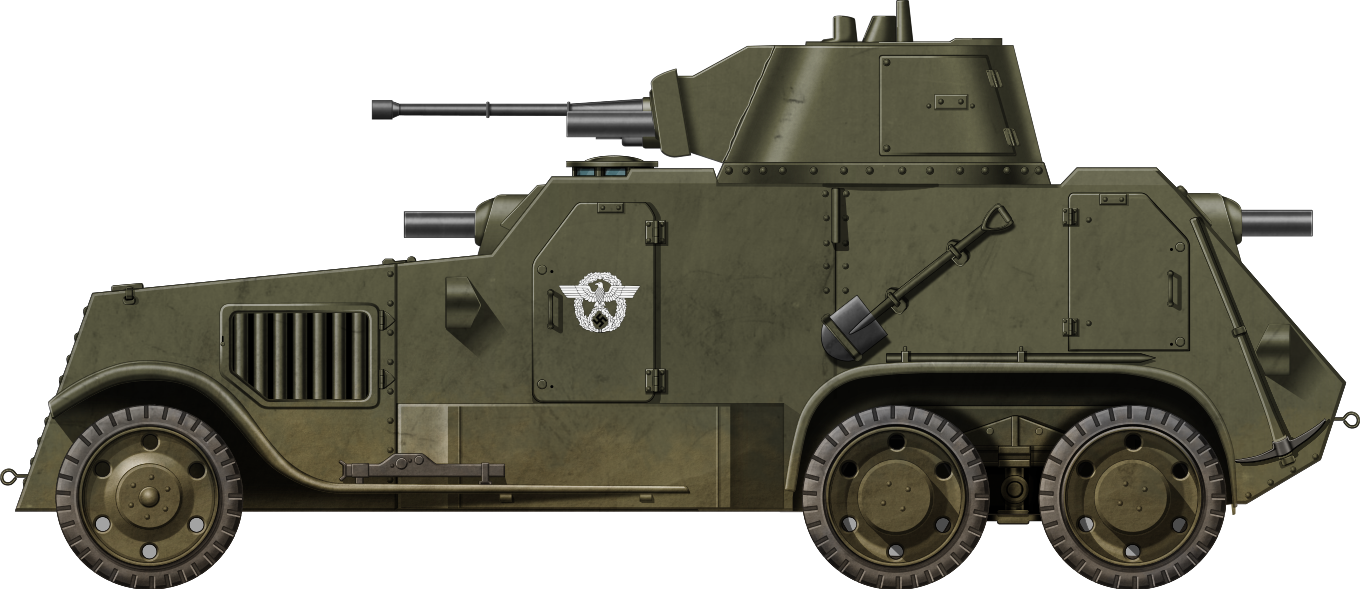

Kingdom of Sweden (1933-1945)

Kingdom of Sweden (1933-1945)

Armored Car – 18 Built

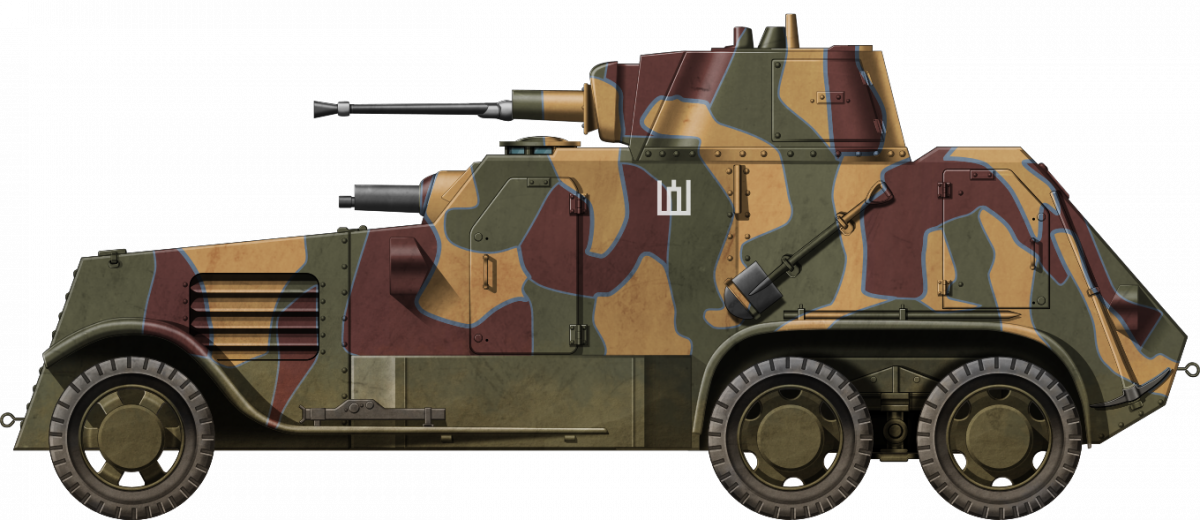

Lithuania (1933-1940)

Lithuania (1933-1940)

6 Purchased

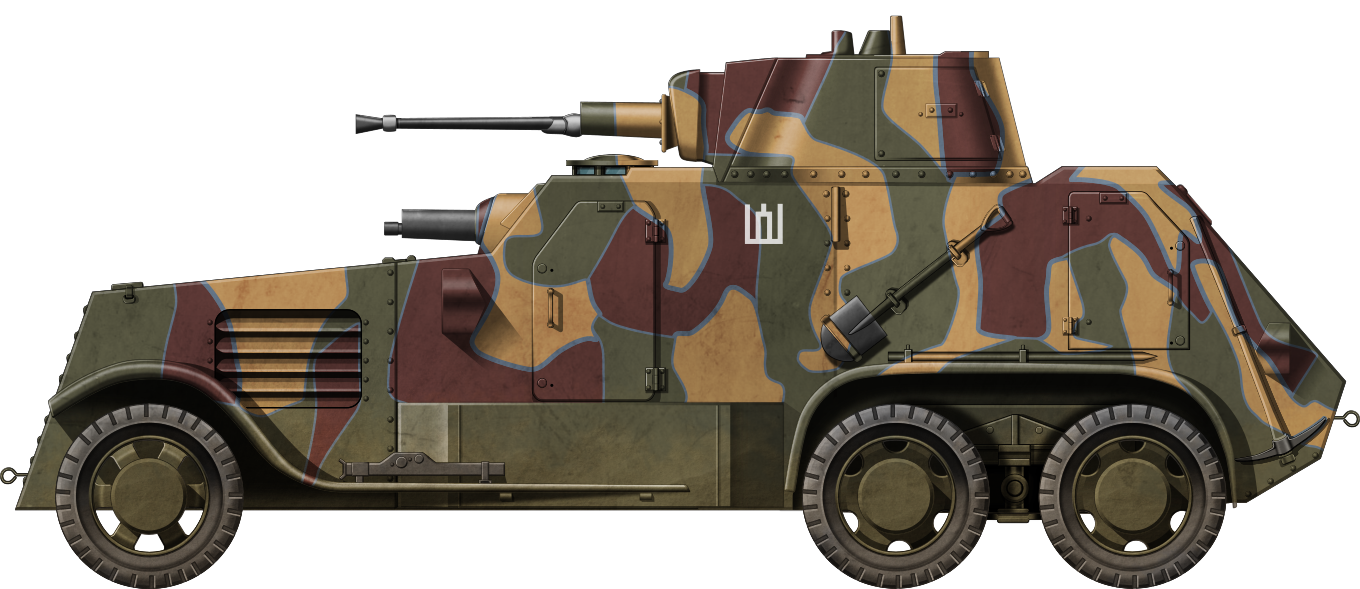

Soviet Union (1940-1941)

Soviet Union (1940-1941)

6 Captured

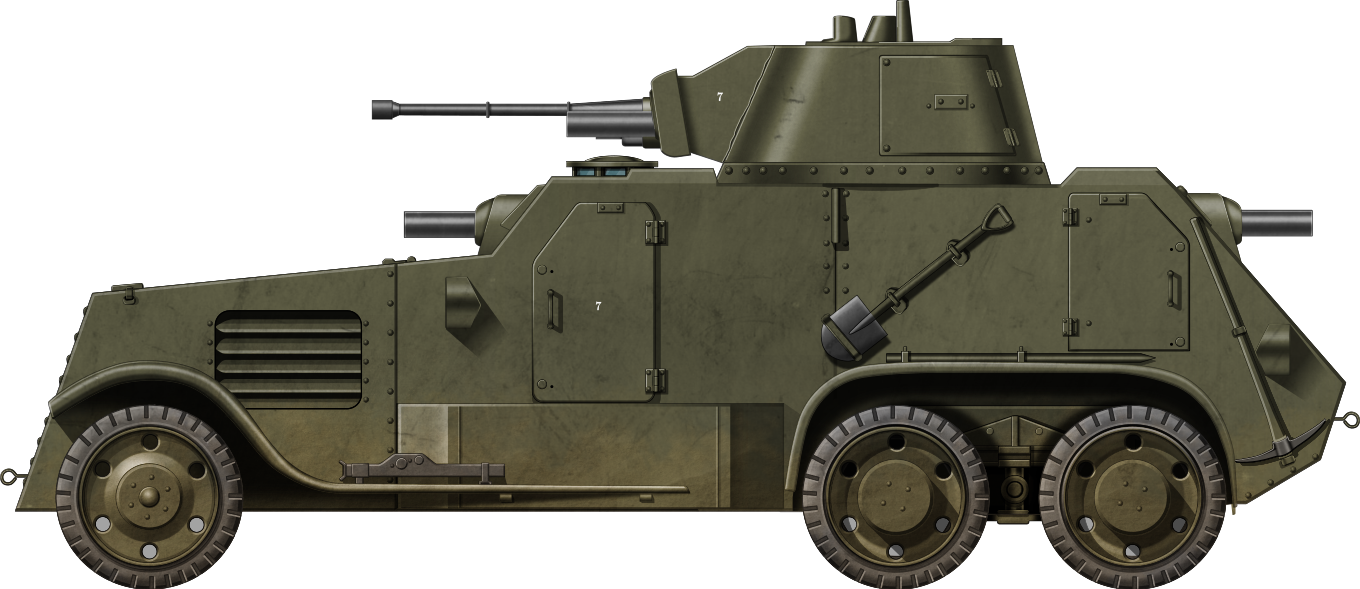

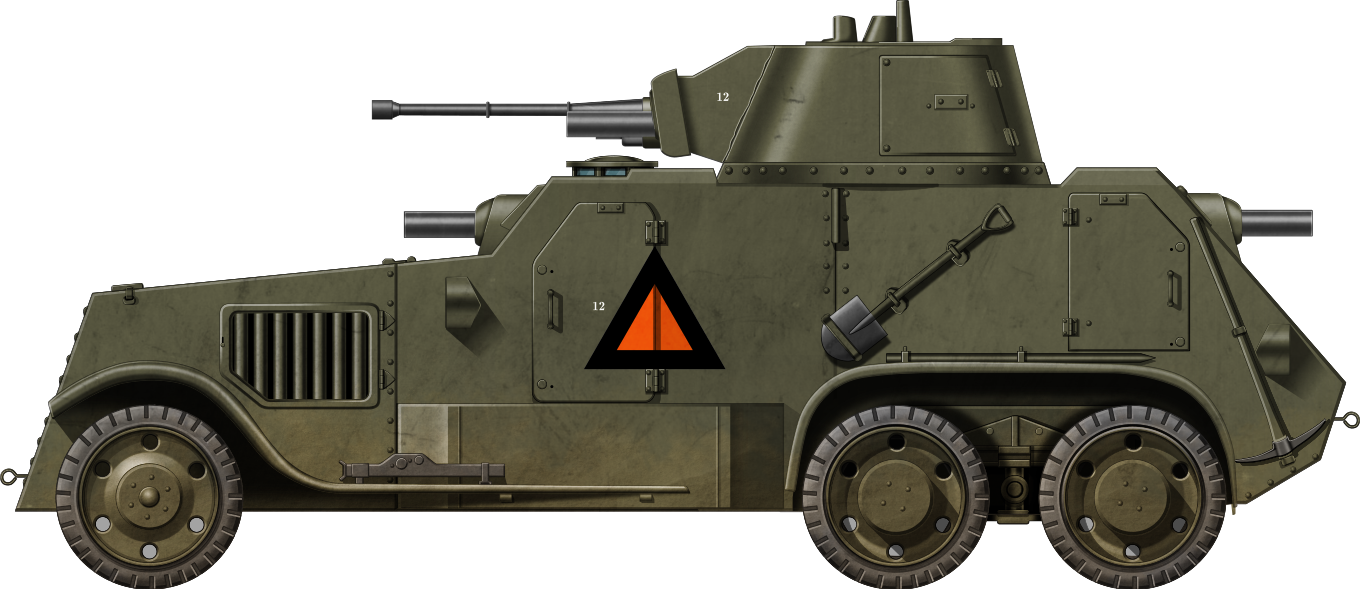

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1934-1940)

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1934-1940)

12 Purchased

German Reich (1940-1945)

German Reich (1940-1945)

12 Captured

The Swedish Landsverk series of armored cars from the Interwar period were a successful export venture, with sales predominantly being made to neutral countries. These armored vehicles all shared the same general design philosophy but differed in the chassis, engines, armament, or smaller details used, based on the customer’s wishes. The Landsverk 181, or L-181 for short, was bought by Lithuania and the Netherlands and in service with the latter, known as Pantserwagen M36. Because the start of the Second World War was characterized by breaches of other countries’ neutrality, several L-181s ended up in the aggressor Soviet and German armies.

Development

The company Landsverk AB was founded in 1872, but found itself on the brink of bankruptcy in 1920. It was bailed out by the German company Gutehoffnungshütte, Aktienverein für Bergbau und Hüttenbetrieb [Eng: Joint Stock Association for Mining and Metallurgical Business, GHH for short], mainly through a Dutch subsidiary called N.V. en Handelsmaatschappij Rollo [Eng: Rollo Trading Company Inc/Ltd], a Dutch company acquired by GHH in 1920.

This system allowed GHH, which also owned the majority of MAN AG at the time, to continue the development of military vehicle technologies, which the Treaty of Versailles prohibited any German entity from undertaking. However, these new military developments by Landsverk were also of interest to the Swedish government, which ordered the chassis for an armored car from Landsverk in 1929. This vehicle, known as the L-170 or Pansarbil fm/29, was ready in 1931, but was very expensive due to the use of advanced and complicated technologies. Therefore, no further orders followed, but it granted Landsverk a great technological base to design new vehicles during the next few years.

The military of Denmark was the first to capitalize on this expertise when they ordered an L-185 in early 1933 after their specifications, which was delivered in December 1933. During the same year, Landsverk began to offer the L-181 that, contrary to the earlier 4×4 L-170 and 4×4 L-185, was based upon a Mercedes-Benz 6×4 chassis. It was offered for 75,000 Swedish Crowns without armament, roughly US$164,000 in present-day values.

As a regular truck chassis was chosen as a base, several changes had to be made to fit an armored body on it. The most important changes were:

- the regular pneumatic tires were replaced by solid Type OH Overman wheels.

- a rearward steering position was added with all the needed controls; steering, hand and foot brakes, foot accelerator, gearstick, and a signaling system.

- a reverse and divisional gear were built in with a common gear lever, mounted by the front driver’s seat.

- the frame and suspension were reinforced.

Due to these modifications, the chassis weight increased from 2,650 kg to 3,200 kg, but this was a good and acceptable weight. A Swedish report from 1935 stated that the new rear steering position was surprisingly stable, considering that the front steering wheels effectively changed into rear steering wheels. A major drawback was the relatively weak engine of 65 hp at 2,600 rpm. This worry was acknowledged by Landsverk itself. As a smaller engine, it would have to produce more rpm during operation and wear out quicker than a heavier engine. Contrary to the engine, the chassis was relatively well-suited for an armored vehicle.

Design

Chassis and Drivetrain

The Landsverk 181 was based upon the 6×4 Mercedes-Benz G 3a U-frame chassis. Development of this truck began in 1929 after an order from the German Reichswehr [Eng. Reich Defense], which was attempting to motorize. The first model, the G 3 powered by an M 09 engine, saw 85 examples produced but an improvement in engine power was requested. In 1932, the first G 3a’s were delivered with an improved M 09 II engine. The G 3a remained in production until 1938 and a total of 2,690 trucks were manufactured. Most of these were delivered straight to the German Army, but some were sold to civilian and corporate organizations, including Landsverk.

The front-mounted Daimler-Benz M 09 II 6-cylinder piston engine had an output of 65 hp at 2,600 rpm, 68 hp at 2,800 rpm, or 80 hp at 3,000 rpm. It had a capacity of 3,663 cmm and a bore and stroke of 82.5 mm and 115 mm respectively. The crankshaft was well-balanced with 7 main bearings, while the valves were driven by a control shaft inside the crankcase. When the vehicle was positioned on a slope, the engine worked fine at inclinations up to 25°. This was sufficient, as a fully loaded L-181 could take slopes up to only 22°. A Bosch 300 Watt generator was coupled to the engine and charged a 12 V 105 Ah battery.

The magneto ignition was also produced by Bosch and featured an ignition timing adjustment system. The fuel was delivered to the engine with a motorized membrane fuel pump and mixed with air by a Solex-Vergaser Typ 40 FHRS Zenith carburetor, equipped with an oiled air filter. The engine was water-cooled by flat radiators, a centrifugal pump, and a special ventilator. The fuel tanks were located at the rear of the vehicle and had a total capacity of 105-125 l. With an average fuel consumption of 2.4 l/km, the L-181 had an operational range of 250-300 km. The engine ran on petrol, but could also use ‘light petrol’, which was regularly used in Sweden and consisted of 25% ethanol and 75% benzene.

Transmission

To enable gear shifting and braking, for which the engine had to be temporarily disconnected from the transmission, a single plate dry clutch was installed. The transmission itself had four forward and one reverse gears. Three of these were quiet gears, as it was a constant gear mesh system that employed helical gears for the power transmission. The helical gears, which have a slanted tooth trace, could be changed through a claw shift with sleeves.

The main transmission was coupled to a secondary transmission, which was operated by another gear shift lever. This added 4 more gears, both for forwards and rearwards driving, increasing the total number of gears to 8 forward and 5 reverse.

From the second transmission, a double drive shaft ran to the first rear axle, and from there, another double drive shaft connected to the second rear axle. Both axles were live beam axles, which is a dependent type of suspension, consisting of a beam that laterally connects two sets of wheels with a single shaft, and was equipped with worm drive and automatic self-locking ZF-differentials. The rear axle ratio was 6.66:1, meaning the drive shaft had to do 6.66 rotations to completely turn an axle once.

| Speed without additional gear | |

|---|---|

| 1 Gear | 13.6 km/h |

| 2 | 22.4 km/h |

| 3 | 46.8 km/h |

| 4 | 62.5 km/h |

| Speed with additional gear | |

| 1 | 4.45 km/h |

| 2 | 7.3 km/h |

| 3 | 15.3 km/h |

| 4 | 20.4 km/h |

| Reverse Speed | |

| 1 | 3.45 km/h |

| 2 | 9.05 km/h |

| 3 | 14.9 km/h |

| 4 | 31.2 km/h |

| 5 | 41.5 km/h |

Mobility

Each of the 6 wheels was equipped with a drum brake, operated by a single foot pedal. The separate handbrake only operated on the first rear axle. The front axle was steered and equipped with single wheels. However, both the solid rear axles were equipped with double wheels, totaling 8 wheels. Each wheel was shod with Overman Type OF bulletproof tires.

The front axle was suspended with semi-elliptic springs. On each side of the rear, semi-elliptic springs were positioned on the left and right of the frame and coupled to each other, and mounted on the frame with a central swivel point. On the ends, they were attached to both rear axles with a ball mount.

Mainly thanks to the two rear-driven axles and the additional gearbox, the L-181 had quite good off-road capabilities. This was further increased by Landsverk providing the option of a chain belt around the rear wheels, enhancing traction and effectively converting the vehicle into a half-track.

The chassis had a wheelbase of 3 m between the first and second axles, 0.95 m between the second and third axles, a gauche of 1.6 m, and a ground clearance of 0.25 m. The vehicle itself had a length of 5.56 m, a width of 2 m, and a height of 2.35 m. The combat weight reached 6,500 kg, with the chassis weighing 3,200 kg, the entire superstructure 2,800 kg, and a payload of 500 kg. With this weight, the L-181 was capable of taking slopes up to 22° or 40%.

Body and Armor Protection

The whole body was designed with as much angled armor as possible, to avoid perpendicular impacts. The only non-angled plate was the housing around the hull-mounted machine gun. The side plates reached an angle of 15°. In terms of thickness, the front, as well as the frontal part of the turret, had a thickness of 9 mm. The sides and rear had somewhat less, with 7 mm, while the floor and roof were 5 mm thick. The armor was made by the Swedish arms manufacturer AB Bofors. Thanks to the combination of armor layout and thickness, the vehicle was protected from small caliber SmK ammunition from further than 124 m when taken on from the front within an area of 120°.

Part of the armored superstructure was bolted to enable disassembly when needed, but most was welded. The radiator of the engine was cooled through six large armored louvers in the frontal armor, while an additional five louvers were mounted on both sides of the engine compartment. This design was disliked by the Dutch, as it still left the engine too vulnerable and they would later replace these with a locally designed system. The upper frontal plate housed a machine gun ball mount on the right and the vision hatch for the driver on the left.

On each side of the hull, a door was placed for the driver and the hull machine gunner. Un-ditching boards were placed under each door. The optional tracks were carried on the rear right side of the hull, above the rear wheel fender, while a jackscrew tool was carried on the board below the driver’s door. A shovel and pickaxe were mounted on the rear left side of the hull, and in between them, a door for the rear driver. A vision hatch for the rear driver was mounted on the rear plate, spanning the entire width. However, on the Dutch vehicles, this hatch was narrowed and an additional machine gun mount was installed on the right side of the hull.

Each door in the hull, and both hatches in the turret, were equipped with a vision hatch and, if closed, still provided vision through a slit with bulletproof glass. If the occupants had to look through these, they could rest their forehead against a leather cushion installed above it for comfort.

Turret and Armament

The center of the turret ring was nearly aligned with the center of the first rear axle. The design of the turret showed a strong resemblance to the earlier developed L-10 and L-30 light tanks, not only externally but also internally, with the weapon mountings and sights. The main armament and a machine gun were mounted parallel to each other in a ‘roller mount’, protected by a mantlet. The roller mount had a depression of -10° and an elevation of +30°. If necessary, the machine gun, which was installed in a separate ball mount, could be detached from the roller mount and aimed independently.

The aiming was achieved with a leveling device, but if the turret had to be turned quickly, it could be temporarily turned off, as manual traverse was quicker. The target was acquired through a Zeiss targeting periscope, built into the roof on the left side, with a visual angle of 40° at a magnification of 1.75 times. This wide view had the benefit that the gunner did not have to continuously turn the weapons to find the target, while the location on the roof provided the clearest view from the highest point. The periscope could be used to aim both weapons, but if the machine gun was disconnected, it had to be aimed separately with the regular iron sight.

The turret was designed in such a way that the commander and gunner were seated side by side on seats fixed to the turret. Three hatches were installed in the turret, one on the roof, and two on either rear side. The commander also had a periscope, mounted to the front right of the turret roof.

A second machine gun was mounted in the hull at the front, beside the driver’s position. Upon special request, the Dutch vehicles had a third machine gun in the rear as well. However, due to limited space, this third machine gun could only be operated if the rear steering wheel was demounted. This was not a large problem, as long the rear driver did not need to switch between firing and driving too quickly. The machine guns could easily be unmounted and, with the gun opening closed by a small round armored plate, deployed elsewhere, either outside of the vehicle or on the anti-aircraft pintle mount on the turret.

The machine guns were protected by an armored cover, which included an aiming sight. In battle, the gunner could be protected with a piece of bulletproof glass, but this refracted the light in such a way that aiming had to be adjusted.

Main Guns

The standard armament that was offered by Landsverk was the Swiss automatic 20 mm Oerlikon 1S. The history of this gun began during the First World War in Germany, when Reinhold Becker developed a 20 mm autocannon. With the armament production limitations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, the documentation and tooling were transferred to Switzerland, where development continued by SEMAG. When this company went bankrupt, everything was taken over by Oerlikon.

In 1927, the new Oerlikon S model was completed, which featured almost double the muzzle velocity compared to the earlier models, and thus became much more effective as an anti-aircraft and anti-tank autocannon, but weighed a bit more, fired larger cartridges, and had a reduced rate of fire. A slightly improved version was introduced in 1930 as the 1S. It had a muzzle velocity of 830 m/s and an effective range of 2,000 m vertically and 4,000 m horizontally. The Landsverk could carry 16 box magazines of 15 rounds each, totaling 240 rounds.

However, the Dutch requirement called for a heavier gun and the Swedish semi-automatic Bofors 37 mm pvkan m/34 was selected as the main armament. This required a larger turret and thus a larger turret ring. A first prototype of this gun was built in 1932, and the Netherlands was the first country to place an order for it in 1935. At this time, it was one of the best anti-tank guns available. It weighed 370 kg and could achieve a rate of fire of up to 12 rounds per minute. Although having a theoretical range of 4.5 km, it quickly lost penetration power over distance. Finnish tests against a 60º angled plate noted 40 mm penetration at 300 m, 33 mm at 500 m, and 18 mm at 1,000 m.

The secondary armament consisted of two or three machine guns, with the specific type to be determined by the user. Lithuania opted for two 8 mm Maxim machine guns. For these, 40 belts of 100 shots could be carried, totaling 4,000 rounds. The Netherlands chose three 7.92 mm Lewis machine guns which were specially modified to be mounted in armored vehicles. The hull machine guns were designated “M.20 No.1 Paw.” and the coaxial machine guns “M.20 No.2 Paw.”.

Operators

Lithuania

The Baltic state of Lithuania proclaimed its independence in 1918, in the wake of the First World War. In 1919, it got its first armored cars, namely a single Russian-built Izhorski-Fiat and five German-built Daimler Behelfswagen, which were regular trucks with improvised armored bodies. But as the years passed by, their combat value decreased to that of training vehicles at best.

To remedy this issue, Lithuania ordered six L-181s from Landsverk on 7th December 1933. The armament was acquired separately, but to be installed by Landsverk as well. Reportedly, several issues and delays arose in the cooperation between Lithuania and Landsverk, and with the production and testing of the new vehicles. On 23rd April 1935, the vehicles arrived in Lithuania and were accepted into service two days later, on the 25th. In June, the issuance to the troops followed.

The 20 mm Oerlikon 1S automatic cannon was chosen as the main weapon of the Landsverk. In 1930, 156 of these guns had been bought from Switzerland, which made them a good option for commonality of ammunition. The Oerlikon was used in various new specialized roles, and also was the intended weapon for the later planned ČKD LTL light tanks. By 1940, the total number had risen to 182. Six of these were in use on the Landsverks.

The two machine guns also came from Lithuanian army stocks and the 8 mm Maxim was chosen. Each vehicle received a unique camouflage scheme, which was painted by Landsverk. The registrations appear to have been applied in Lithuania. The Landsverk company also numbered the vehicles: 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34, but it is unclear which number corresponded to which Lithuanian vehicle.

| Lithuanian Registrations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Registrations | Landsverk Numbers | Engine Numbers | Serial Numbers |

| K.A.M. No.5 | ? | 98482 | 10445 |

| K.A.M. No.6 | ? | 98481 | 10446 |

| K.A.M. No.7 | ? | 98487 | 10447 |

| K.A.M. No.8 | ? | 420941/05 | 10448 |

| K.A.M. No.9 | ? | 98485 | 10449 |

| K.A.M. No.10 | 32 | 98492 | 10450 |

Service

The vehicles were organized into the 1st Armored Car Company and divided into three platoons. Vehicles 9 and 10 were assigned to the 1st Hussar Regiment [1-asis husarų], which was normally stationed in the Žaliakalnis barracks in Kaunas. Vehicles 7 and 8 went to the 2nd Uhlan Regiment [2-ajame ulonų] stationed in Alytus, and 5 and 6 went to the 3rd Dragoon Regiment [3-iajame dragūnų] in either Katyčiai or Macikai. Each pair operated as a platoon within their respective cavalry regiment and were used for training.

| Unit | Vehicles | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Hussar Regiment | 9 & 10 | Kaunas |

| 2nd Uhlan Regiment | 7 & 8 | Alytus |

| 3rd Dragoon Regiment | 5 & 6 | Katyčiai/Macikai |

By the late 1930s, Lithuania was confronted with increasing pressure from its bordering giants, Germany and the USSR. The first territory loss was suffered in March 1939, when a German ultimatum was accepted and the entire Klaipėda Region was ceded to Germany. As a consequence, the 3rd Dragoons were relocated. Germany would not take more land from Lithuania.

On 23rd August 1939, Germany and the USSR signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and, while Lithuania was initially in the German sphere of influence, this was changed to the Soviet sphere. The USSR already capitalized on this in October, when Lithuania was forced to agree to five Soviet military bases inside their borders, although they got the Vilnius region in return, which the USSR had captured from Poland and Lithuania desired for a long time.

Yet, Lithuania’s integrity was falling apart and, on 14th June 1940, it received a Soviet ultimatum for a de facto occupation. Realizing any resistance would be futile, the government went into exile and the Red Army swiftly poured into the former sovereign and neutral country.

Soviet Service

Under Soviet rule, the Lithuanian Army was not disbanded, but rather reformed, first into the short-lived Lithuanian People’s Army and later into the 29th Rifle Corps. The Landsverks also found their place in this new force. No. 7 and 8 of the 2nd Uhlan Regiment went to the reconnaissance battalion of the 184th Division and no. 9 and 10 of the 1st Hussar Regiment went to the reconnaissance battalion of the 179th Division. Meanwhile, 5 and 6 were allocated to the 615th Artillery Regiment.

On 22nd June 1941, Germany invaded the USSR, which directly led to an uprising in Lithuania against the Soviets, whose rule had been generally very unpopular. Part of the 29th Rifle Corps also joined in and two Landsverks, present at the Pabradė training ground northeast of Vilnius, were deployed against the Soviet troops. In the fighting, one was destroyed and the crew was killed. The other survived and was handed over to the Germans.

The other four L-181s were pulled back by the retreating Red Army and their fate after that is unclear. They may have been used on the front, or for examinations. One Lithuanian source even mentions they may have been sent to Korea in 1950, as US troops allegedly photographed them there, but without any evidence to back this up, this seems highly unlikely.

The Netherlands

In the early 1930s, it was finally realized by the Dutch Army that there was a need for modern armored combat vehicles, especially in the roles of reconnaissance and security. This also required a certain level of off-road performance and a large operational range, which was not achieved by the few armored vehicles that were used in the Netherlands by that point, most notably the three Morris armored cars from 1933 and five Carden-Loyd tankettes. Other requirements included sufficient protection against small arms and machine gun fire and shrapnel, a turret armed with a gun and a machine gun, as well as one to two machine guns in the hull, a good acceleration to evade enemy fire, and a rear driving position.

After a list with these requirements was compiled, the specially appointed armored car commission [Dutch: Commissie Pantserautomobielen] considered proposals by Renault and Citroën from France, Fiat from Italy, and Landsverk from Sweden. The L-181 was eventually selected against options such as the Autoblindata Fiat-Ansaldo su chassis Fiat mod. 611, the Citroën P16, P28, and possibly also the Berliet VUDB-4.

On 28th December 1934, the order was placed for twelve L-181 armored vehicles which were to form a single armored car squadron. Some modifications were arranged with Landsverk to comply with the requirements. Most importantly, a 37 mm m/34 Bofors gun was selected as the primary armament, which required the slight enlargement of the turret ring. Additionally, a third machine gun position was added in the rear of the hull.

Preparations

For several months, the head engineer of the state-owned Artillerie Inrichtingen [Eng. Artillery Establishments, a gun and ammunition manufacturer], S. de Haan, was detached to the factories of Landsverk and Mercedes-Benz to thoroughly study the new vehicle. In a similar fashion, Lieutenant Jelgersma, who had earlier worked on the solution to fit a Schwarzlose machine gun in the turret of the single Dutch Renault FT, was detached to Bofors to study the new 37 mm gun. In addition, he visited a Swedish tank battalion in Stockholm. The future commander of the unit, Ritmeester [Eng. Captain] H. Wilbrenninck, was detached to the German training unit for Schnelle Truppen [Eng. Fast Troops] in Munster.

Some Controversies

A small discussion arose regarding the army branch that was to operate the new vehicles. The commander of the Field Army, Lieutenant-General Squire W. Roëll, was strongly in favor of assigning the new vehicles to the Mobile Artillery Corps, because they operated all the armored vehicles that were already in the Army’s possession. This was against the wishes of commanders of other army branches and the cavalry was selected as the future operator instead.

A somewhat larger discussion arose later in the Tweede Kamer [Eng. Second Chamber, the Dutch House of Representatives]. The vehicles had been ordered in 1934 but at that point, the decision and budget change had not been discussed, nor approved, by the Second Chamber. While the need for a swift decision was understood, it was considered a bad practice that only in October 1935 were the needed funds requested and that this budget request was not discussed earlier than March 1936.

The Minister of Defense, Hendrikus Colijn, disagreed with this allegation, as he argued that funds were taken from the budget item for the acquisition of artillery material, for which 6,476,246 Guilders had been set aside, and which item was only exceeded by 300,000 Guilders, and this had already been compensated by savings on other items.

Delivery

Throughout 1935, the future war organization of the squadron was worked out by the Commander of the Field Army, and the Inspector of the Cavalry, who was simultaneously the Commander of the Light Brigade [a mobile unit that was to cooperate with the armored cars in the future]. Based upon their suggestions, the Minister of Defense set out the final organization that included a squadron staff with a command group, a medic group, an administrative group, four battle platoons with three L-181s each, as well as a machine gun group on motorcycles, and for the logistical support a battle train, kitchen train, provisions train, and a supply train. The squadron commander used a civilian car incorporated into the command group.

The peacetime organization looked quite different, with just a squadron staff, including the mobilization bureau, and three training platoons. The southern city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch was selected as the garrison city, already housing the Light Brigade, and being close to the defensive Peel Line.

In the original contract, delivery was stipulated to take place in November and December 1935. This was met with slight delays, and the first six vehicles were delivered by January 1936. Another batch was shipped to the Netherlands in early February and all had arrived before 1st April. After arrival, the vehicles were moved to the Ripperda Barracks in Haarlem, home to the Korps Motordienst [Eng. Motor Service Corps], where the first training and familiarization with the vehicles took place.

Already before the squadron was established, one M36 was experimentally fitted with a radio. In order to fit it, the frontal hull machine gun had to be removed and a collapsible antenna was mounted to the right side of the hull. However, the modification was undone, and no radios would ever be fitted for operational use. Although the decision was made in early 1940 to eventually install radios in all armored vehicles, the modification came too late to be implemented before war broke out.

Nomenclature and Registrations

Because the Landsverks were taken into service in 1936, they were officially designated as Armored Car Model 1936 [Dutch: Pantserwagen M36]. The M.36 way of writing is most common, but ‘M36’, ‘M 36’, or ‘M-36’ were also used on occasion.

| Registrations of the 1st Armored Car Squadron | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Civilian License Plate | Vehicle Number | Military registration | Military license Plate |

| N-43671 | 1 | 1251 | III-601 |

| N-43672 | 2 | 1252 | III-602 |

| N-43673 | 3 | 1253 | III-603 |

| N-43674 | 4 | 1254 | III-604 |

| N-43675 | 5 | 1255 | III-605 |

| N-43676 | 6 | 1256 | III-606 |

| N-43677 | 7 | 1257 | III-607 |

| N-43678 | 8 | 1258 | III-608 |

| N-43679 | 9 | 1259 | III-609 |

| N-43680 | 10 | 1260 | III-610 |

| N-43681 | 11 | 1261 | III-611 |

| N-43682 | 12 | 1262 | III-612 |

| N-48359* | C1 | – | III-613 |

* This was a command version of the later acquired and different Landsverk 180 [Pantserwagen M38].

The vehicle numbers were painted in white on the front above the radiator, both doors, on the turret, and on the rear. The vehicles also received a civilian registration. This was painted on the front and rear of the vehicle, with white on a blue background. The prefix ‘N’ stood for the province of Noord-Brabant, where the vehicles were stationed. This was followed by five numbers. Thirdly, each vehicle received a military registration. This was a combination of four digits, painted on a small rectangle with three diagonal red-white-blue stripes. These rectangles were painted on the front and rear.

In 1938, this registration was changed due to the implementation of a new system. The Landsverks received a registration starting with ‘III’ (cavalry branch), followed by a new three digit number. In 1939, this number also replaced the civilian license plate. The new military license registration was painted with black on an orange rectangle.

During the mobilization, in 1939, the vehicles were further outfitted with clear nationality symbols. These consisted of a large orange triangle with a black border. It was painted on the front, rear, both side doors, and on top of the engine compartment. Although far from ideal for camouflage purposes, it would prevent any case of friendly fire.

The Armored Car Squadron

The core of 28 men for the new squadron was sourced from the Hussars and Cyclist Regiments. Training started from the very end of 1935 and the soldiers were detached to the Motor Corps in Haarlem. This was followed by a course in armored car technology at the Artillery Establishments.

On 1st April 1936, the squadron was officially established. On that day, all twelve armored cars moved in parade from Hembrug via the route Amsterdam-Naarden-Soestdijk-Utrecht-Vianen-Culemborg-Hedel to their garrison city, ‘s-Hertogenbosch. By this time, the squadron was far from being completely equipped. It would take a year and a half before this was done. However, the twelve armored cars were present and, in September 1936, two platoons were able to participate in the yearly autumn army maneuvers, this time held in the province of Noord-Brabant. The maneuvers in the vicinity of Rucphen were also observed by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, as well as her daughter, Princess Juliana, and Prince Bernhard.

Initially, it was thought that the squadron could permanently be stationed in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, in the Isabella Barracks. However, space was limited, and it was therefore decided to build a new barracks near the city of Vught, still close to ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Construction began in autumn 1936 and the armored car building was officially opened on 19th May 1937. Personnel remained in the Isabella Barracks until new barracks were completed on 12th April 1939.

Reception of the M36

The general reception of the M36 was rather good, but some shortcomings were still encountered during the years of service, ranging from lack of protection to improper fittings. Eight major points were noted down:

- the M36 lacked floor armor.

- the engine shutters did not provide enough protection to the engine.

- the turret hatch could not be safely closed when under gunfire.

- there was a lack of observation equipment for the driver and machine gunner when their hatches were closed.

- a ventilation system was missing.

- the exhaust muffler was mounted too close to the storage space of the searchlight.

- it was impossible to lock the hatches from the inside.

- the sighting prisms were easily damaged due to faulty mountings.

In theory, most problems could be solved with a few easy modifications, but in reality, only the engine shutters problem was solved by the time the war broke out. The new shutters were solidly mounted in a vertical position on the sides, and horizontally on the front. The modification was installed at the end of 1939. At least one vehicle was not equipped with the new frontal shutters by May 1940.

Because the M36s were heavily worn out due to their intensive use, a decision was made in January 1940 to replace them with 13 new armored vehicles from DAF, prematurely designated as the M40. Delivery was expected no earlier than 1941, but the outbreak of war prevented this project from evolving past just planning.

Mobilization

Because the squadron was part of the combined border, coast, and air defense forces, it was among the first to be mobilized in case of increased threat. The Sudetenland conflict in September 1938 was the first trigger. The squadron, having just finished the general autumn army maneuvers, was kept mobilized until early October.

The second time came not too long after, in early April 1939, following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia and the Italian attack on Albania. The squadron was still mobilized when the general mobilization followed at the end of August. In early September, the squadron was moved to Mierlo-Hout, where it was stationed for several months. It was followed by a short stay in Boxtel and, at the end of November, it was moved to Breda. Because of the German attack on Scandinavia in April 1940, and their swift attacks on the airfields, it was decided in that month to relocate the squadron to two important airfields, Ypenburg near The Hague, where the government was seated, and Schiphol, near the capital, Amsterdam.

The 1st and 2nd Platoons at Ypenburg

On 20th April, the 1st and 2nd Platoon, under command of 2nd Lieutenant (res.) M.J. Aldenkamp were ordered to Ypenburg Airfield. The airfield was further guarded by the III Battalion of the Grenadiers Infantry Regiment under the command of Major (res) E.C.F. ten Haaf. These units were put directly under the Commander of the Air Defense, Lieutenant-General P.W. Best, as the Major held a higher rank than the commander of the airfield, Captain H.J.G. Lambert.

The airfield defense was organized into an interior defense under command of Captain (res.) W.J. Moulijn, an exterior defense under the command of Captain (res.) O.K. Bartels, and a reserve force. The interior defense had to protect the airfield from airdrops on the airfield itself, while the exterior defense had to protect the airfield from paratroopers or a potential ‘fifth column’. The latter defense was organized into three ‘shields’, Hoornbrug to the northwest, Broekpolder to the west, and Delft to the southwest of the airfield.

Landsverk 601 was the only vehicle attached to the exterior defense and placed near the road outside the main entrance to the west of the airfield. The other five Landsverks were attached to the interior defense and spread out over the airfield, but remained close to the buildings and were camouflaged. Interestingly, the Germans were aware of the presence of armored vehicles. In their assault plans, it was noted that the armored vehicles were either to be captured and be employed for their own use, or, if not possible, be destroyed.

10th May: The Attack

Following the first alarms, all defenders had taken their positions by 3.30 in the morning. Half an hour later, the first German bombers began their bombardment, but the first bombs missed. Bombing continued until 4.45, followed by strafing from Messerschmitt Bf 110s. The damage was rather limited in respect to the intensity of the attack, but it had significantly lowered the morale of the defenders and also caused some problems for the Landsverks. Landsverk 602 stood next to a hangar that was hit by a bomb and thus had to relocate. Landsverk 601 of the outward defense had sunk into a bomb crater and was too stuck to be recovered. Landsverk 605 reportedly suffered a malfunction to the aiming equipment and its periscopes were damaged.

Around 5.20, the Germans tried to land with airplanes on the airfield. However, the first landing group was heavily attacked by machine gun fire and fire from the armored cars. Most planes burst into flames and the German troops were annihilated. A second landing group met the same fate, and a third group lost several planes in the sea of flames, before more landings were called off. Although these landings on the airfield were unsuccessful, other planes had landed on fields in the vicinity and these airborne troops joined German paratroopers in an advance on the airfield from the outside.

The German advance initially succeeded. Around 7.15, German troops had captured the main building on the airfield, as well as its surrounding area. Shortly thereafter, they took the Dutch southwestern positions, thus taking most of the airfield. Dutch forces retreated and more were gathered from other locations in preparation of a counterattack. After an artillery barrage, troops advanced, but were then called back, as a requested British air bombardment was incoming. This British bombing raid took place around 15.10, after which the Dutch troops advanced again on Ypenburg. This counterattack was successful and, by the evening, the whole of Ypenburg and surrounding area were cleared of German soldiers, granting a victory to the Dutch defenders.

Because of the intensity of the fighting, but also the available detailed fight reports, the actions of the armored cars and their respective crews will be presented per vehicle.

| 601 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | ? | ? | ? |

| Corp. Doelman | Wm. Van der Horst | Bunnik | Jongsma | Van Lent |

Landsverk 601 had sunk away in a bomb crater after the initial bombing and was unable to be moved. Despite this, the crew remained in the vehicle and fired at incoming planes. However, being just outside the airfield perimeter, effectiveness was limited by trees between the vehicle and incoming Germans.

Around 7.00, German units advanced to the main entrance, using several Dutch POWs as human shields. Dutch forces defending the entrance were unwilling to fire on their own, thus they were quickly overrun. Landsverk 601 was surrounded, but while the crew tried to fight them off, the Germans threatened to throw grenades under the vehicle, which would be fatal, as it had no floor armor. Therefore, the crew surrendered.

| 602 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | Driver | Machine gunner | Rear driver |

| Corp. Mommaas | Corp. Cools | A. Fikkers | Hummel | Van Breugel |

Landsverk 602 stood positioned between a hangar and a small wall of stacked bricks. After being hit by a bomb, the hangar caught fire. While the vehicle initially remained in its position and fired upon the German attackers, the fire spread quickly, so they needed to evacuate. Commander Corporal Mommaas decided to relocate to the Sintelweg, a road between the airfield and Hoeve Ypenburg to the northwest. After repositioning, fire was opened again. Main driver Fikkers decided to mount one machine gun on the anti-aircraft pintle mount and opened fire on the German planes while standing on the rear mudguards.

After the ammunition stocks drew threateningly low, Mommaas decided to continue to Hoeve Ypenburg, where the trucks with ammunition were located. There, ammunition was restocked, but Mommaas realized that the other crews would likely need more ammunition too. Taking the initiative, he handed over command of 602 to the gunner, Corporal Cools, as he took an ammunition truck and drove it unto the airfield, where he supplied 608 and 611 with ammunition. His third destination was 601, but before he got there, the truck was disabled by German fire.

By chance, another truck of the Motor Service drove by, and ammunition was quickly reloaded onto this truck. After this short intermezzo, he continued his journey with this truck, but it also came under German fire, killing the driver. Corporal Mommaas remained unharmed and hid from advancing German forces, after which he retreated to Hoeve Ypenburg and rejoined his crew.

Landsverk 602 was then ordered to advance to the main motorway alongside the airfield via the main entrance. On the road, the front machine gunner Hummel fired upon Germans hiding in ditches, but was unable to fire on Germans standing on the road, due to the presence of Dutch POWs. During this patrol, the radiator was shot through and damaged, causing the vehicle to retreat to the north to the Hoornbrug. There, it was pulled into a defensive position with a confiscated civilian tractor. That an armored car was still effective, even in a static position, was demonstrated by the crew, as they managed to take down two enemy planes with combined cannon and machine gun fire.

| 603 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | Driver | Machine gunner | Rear driver |

| 2nd Lt. M.J. Aldenkamp* | Koopmans | N.T. de Vries✝ | H. Betten | Corp. van Essen |

*Also the commander of both platoons

During the bombardment, the aiming equipment of 603 was disrupted. After recalibration, the crew was able to partake in giving fire against the landing German aircraft. As the vehicle lacked a working rangefinder, machine gunner Betten put his head out of the vehicle each time the gunner needed a range estimation. After the vehicle ran out of shells, Betten collected eight shells from 608, which stood relatively close, by foot. Around 6.00, the commander, 2nd Lieutenant Aldenkamp, left for an inspection of the situation to report this to the commander of the Grenadiers Battalion. After finishing his report to the commander and leaving the command post, he noted how the situation had deteriorated, and ordered his crew to advance from its position and attack the enemy from around the main building.

In the attack, 603 came under heavy German fire. The driver, N.T. de Vries, was killed when they were near the gate to leave the airfield. The vehicle kept moving until it came to a sudden halt against an ammunition vehicle. Gunner Koopmans was also wounded. As De Vries was carried out of the vehicle, Lieutenant Aldenkamp returned to the vehicle, but promptly left, overseeing the new situation.

Betten took position at the front wheel, but when he ordered to reverse, he realized there was no rear driver. He left the vehicle to take the position himself, but as he left the protection of the vehicle, he was captured by German troops.

| 605 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | Driver | Machine gunner | Rear driver |

| ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

Like 603, the aiming equipment of 605 was disrupted because of the bombardment, but additionally, its periscopes were also damaged. Due to bomb impacts around the vehicle, the crew was unable to relocate and decided to abandon the vehicle. Instead, they took defensive positions with their demounted machine guns alongside some other machine gun units that were positioned on the airfield.

A short while later, a large plane was shot down and crashed near the Landsverk. A Hussar, originally attached to the motorized machine gun group of the platoon, decided to go to the Landsverk, which was unmanned at that time, to fire at the plane with the cannon to destroy it completely. The cannon was loaded, so he could fire once, but he missed. Reportedly, there were no other projectiles left in the vehicle.

The crew, alongside the other machine gun troops, remained in their position until the end of the afternoon, when they finally retreated on foot. The Landsverk was left behind.

| 608 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | Driver | Machine gunner | Rear driver |

| Wm. G. Bonga | Corp. Sleeuwenhoek | A. de Bruin | J.G.M. de Vries✝ | C.P. Joosen |

Landsverk 608 came through the bombardment unscathed and could open fire on the landing German planes without much trouble. However, three trucks that stood in the line of fire had to be driven away while under fire.

During the later German land attack, Landsverk 608 tried to aid the counterattack by 602 and 603. However, the vehicle eventually found itself between attacking Germans and vulnerable Dutch POWs. With difficulty, the crew maneuvered itself out of this precarious situation, but the machine gunner was fatally wounded in the action.

Meanwhile, 2nd Lieutenant Aldenkamp, the commander of both platoons, was still out on foot. When he retreated from the advancing Germans, he found 608 positioned near the canteen. He ordered the crew to make some reconnaissance rounds over the airfield to determine the enemy positions, because fire was received from the northeast as well, while the German attack came from the southwest. The crew was able to determine that the fire from the northeast came from Dutch troops, but both drivers of 608 were wounded in the attempt.

After retreating to its position at the canteen, the vehicle and 2nd Lieutenant Aldenkamp remained there until 10.00. With both drivers wounded and the gunner fatally wounded, Aldenkamp decided to retreat to Hoeve Ypenburg. On route, they encountered several Dutch troops, which received intelligence from Aldenkamp, who also gave one machine gun to the infantry. At Hoeve Ypenburg, 608 was left behind and Aldenkamp further retreated to the Hoornbrug, where 602 and 611 were already present.

During the Dutch artillery fire on Ypenburg, preceding the British bombing and Dutch counterattack, the commander of Landsverk 601 managed to escape and fled to Hoeve Ypenburg, where he found Landsverk 608. With this Landsverk, he also retreated to the Hoornbrug, where 608 was positioned on the Haagweg.

| 611 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gunner | Driver | Machine gunner | Rear driver |

| ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

Little was reported about Landsverk 611, which also successfully fired upon the incoming German aircraft. During the German land attack around 7.00, 611 was also unable to open fire, due to the presence of Dutch POWs. When it was attacked from the rear, the commander decided to abandon its position and move to the motorway. When it found that the main entrance was blocked, it retreated via the airfield and the Sintelweg. During this attempt, some camouflage was detached by the wind and blocked the periscopes on the turret. Unable to safely remove it, the crew decided to retreat to Delft. After the camouflage issue was fixed, they returned to the Hoornbrug. However, during this maneuver, the vehicle came under enemy fire and the aiming sight, as well as the bulletproof glass of the front hull machine gun were damaged. The machine gunner was lightly wounded. After arrival at the Hoornbrug, the Landsverk was placed in a defensive position on the road to Den Haag.

Shortly after 12.00, 611 was ordered to advance to Delft via a reroute and be deployed against German planes that had landed in that area. However, the gun malfunctioned and the crew decided to visit the Artillery Establishments in Delft. After redeployment, the gun malfunctioned again, thus the crew visited the Artillery Establishments again. They stayed in Delft overnight.

The Situation at the End of 10th May

After Ypenburg was recaptured, Lieutenant Aldenkamp pulled the remnants of his two platoons back to Rijswijk. At this point, Landsverk 611 was in Delft, 602’s radiator was still broken so it had to be pulled, while 601, 603, and 605 had been left behind at the airfield, thus only 608 was available for immediate action at this time.

The armored car crews had suffered moderate casualties. In total, four soldiers were wounded, N.T. de Vries was killed, and soldier J.G.M. de Vries was fatally shot in the stomach and died in hospital sixteen days later.

11th May

In the early morning of 11th May, both platoons and their two Landsverks, with 602 being towed by 608, were moved to the main headquarters of the Air Defence Command in The Hague, at the Juliana van Stolberglaan. There, the platoons were placed under the command of the Guards Detachment from the Cavalry Depot, Major (res) V.F.W. Overbeck. Landsverk 602 was towed to a local Mercedes-Benz car dealer to undergo repairs to its radiator. After taking a short rest, some of the soldiers returned to Ypenburg at 11.00, to recover the three Landsverks that had been left behind.

Vehicles 601 and 603 were quickly recovered and also arrived at the Air Defence Command headquarters. There, they joined 608 in defensive positions around the headquarters. This high level of security was deemed necessary due to high unrest in The Hague caused by fear of German infiltration, both in the form of paratroopers and German-aligned civilians (called a fifth column).

Landsverk 605 was unable to join the platoons, as it was halted in The Hague by other Dutch units to provide support against alleged German troops that were moving around on the roofs of buildings. These fears turned out to be ungrounded, but the Landsverk was requisitioned nonetheless, and put under direct command of the Command of Fortress Holland. It patrolled through Scheveningen and the crew stayed overnight in the vicinity of the Fortress Holland headquarters.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Aldenkamp tried to find the necessary replacements for lost materiel and a new radiator for 602. New ammunition was found at the Cavalry Depot at the Frederik Barracks. The spare M36 chassis turned out to be present there as well, and it was decided to take its radiator as a replacement for 602.

Landsverk 611 was still in Delft. Since the gun was still broken, only the machine guns could be used during some sorties against some remaining German airborne troops that were still present in the vicinity of the city. Later that day, it moved to the Cavalry Depot in the Hague to have the gun fixed. After some shooting trials on the beach, the vehicle moved to Rijswijk, assuming both platoons were still stationed there. However, a report that German troops were present in the vicinity of Vliet caused the crew to abandon this plan. Instead, it patrolled through The Hague until the evening, when the crew stayed overnight at the Cavalry Depot.

12th May

Using the spare radiator, 602 could be repaired on this day. It was immediately put to use as an escort for an anti-air column that had to move from The Hague to Delft. It returned after finishing this task. The other available armored cars were used for many patrols and small tasks, for which a swift and protected vehicle was deemed necessary. Landsverk 601 was ordered to take a defensive position at the Haagse Golfclub (Eng. The Hague Golfing Club) for the whole day. Landsverk 608 was manned by Lieutenant Aldenkamp and partook in a reconnaissance mission to Voorburg, as Germans were reported hiding out in some industrial buildings. This report turned out to be ungrounded. An unspecified armored car supported some house searches near the Laan van Meerdervoort.

After their nightly stay at the Cavalry Depot, Landsverk 611 was used to guard several houses in The Hague.

Landsverk 605 was ordered to advance to Scheveningen after German patrols were reported there. At some point during the journey, the turret had been turned to the side, thus the gun was extended quite a bit from the vehicle. As luck may have it, the vehicle drove too close to several trees, crashing the barrel into these. As a result, the aiming devices were heavily damaged. Following this, the vehicle returned to the Lange Voorhout in The Hague, where it joined most of the 2nd Armored Car Squadron that had been ordered there as well.

13th May

Following up on the deteriorating military situation, the decision was eventually made that Queen Wilhelmina was to evacuate. After her example, the government decided to follow suit in the afternoon. A column of civilian cars was gathered and moved from The Hague to Hook of Holland, to board a ship to England. The column was protected by Landsverk 601 and 602.

Landsverk 608 was also used, but to escort a column of Grenadiers from The Hague to Delft.

Landsverk 605, still present at the Lange Voorhout with the 2nd Squadron, was outfitted with a new aiming device. After this repair, it rejoined the 1st Squadron at the Juliana van Stolberglaan.

Landsverk 611 finally returned to the platoons.

14th May

After their task in protecting the fleeing government, Landsverk 601 and 602 returned to The Hague in the early morning of 14th May. It appears that most, if not all six armored cars were present at the Juliana van Stolberglaan when the Dutch Army Command decided to capitulate. This decision was made around 17.00, following the devastating bombardment on Rotterdam. The squadron laid down arms, and moved to the Frederik Barracks in The Hague. There, the Landsverks were found by the German occupiers.

The 3rd and 4th Platoons at Schiphol Airfield

On 29th April 1940, the 1st Squadron, without the 1st and 2nd platoons, was moved to Schiphol Airfield, near Amsterdam. The Squadron was placed under the command of Major G.P. van Hecking Colenbrander, the Airfield Commander, who could also count on the 1st Battalion of the 25th Infantry Regiment. The attached Landsverks were 604, 606, 607, 609, 610, 612, and the L-180 Command 613.

The Command Group, with the 3rd Platoon under command of 1st Lieutenant (res) H.P. de Kanter and the medical aid unit, were located near the buildings to the southeast of the airfield. The three armored cars and the command car were positioned in a line in front of the buildings. In case of an attack on the airfield involving airborne landings or paratroopers, the armored cars were to clear out any infiltrations in and around the buildings, in cooperation with infantry. This interior defense was under command of Major (res) A.G. Cool, the commander of the Infantry Battalion. The administration, corps train, and half of a motorized machine gun group were stationed in the nearby village of Badhoevedorp.

The 4th Platoon was stationed on the Meerdijk, a dyke/road 600 m to the north of the airfield, together with the other half of the machine gun group and some infantry. The platoon was under command of Kornet [Eng. Officer Candidate] A.L. van Reenen. All the weapon positions and armored vehicles were continuously guarded. Together with the infantry, which had a bus for troop transport at its disposal, this unit was meant as a mobile force, to be deployed against outside attacks on the airfield.

Attack on Schiphol Airfield

On 10th May, around 2.00 in the morning, the alarm was raised at Schiphol, after which all units moved to their fighting positions. At 3.58, the first bombardment began, which was followed by multiple bombing and firing raids, with short intermezzos, lasting for roughly two hours. Most of the hangars and surrounding buildings were destroyed, but the airstrips were left intact. This raised the fear that the Germans were planning a landing at Schiphol too. During the attacks, some casualties were taken. A Landsverk was damaged and penetrated by enemy fire. However, the armored cars did not fire a single shot, as this was forbidden until enemy forces would actually land on the airfield. This was to prevent Dutch planes, located in the fields surrounding the airfield, from getting damaged by friendly fire.

Shortly after the attack, the M38 command car was moved to defend the central command post, as ordered by Airfield Commander Major Cool.

After the reports came in from Ypenburg, the squadron was ordered to open fire on enemy planes already before they attempted to land, contrary to the earlier decision to hold fire as long as possible. It was also planned to let the Landsverks drive up the airfield. The 4th platoon was ordered to support in such an attack. Around 7.00, Major Cool ordered it to take position in the village Badhoevedorp. The squadron commander, Wilbrenninck, and the platoon commander, Van Reenen, worked out a defensive strategy. In case of landings, the 4th Platoon was to relocate to the Schipholweg, a road alongside the airfield and take position to the southwest. If needed, they could drive onto the airfield.

However, despite numerous warnings and indications, the Germans did not launch an attack on Schiphol. This left the squadron idle, only busying itself with patrols, for which a Landsverk was used just once. In the afternoon of 13th May, the 4th Platoon was split up, with one vehicle ordered to guard the Sloterbrug, a bridge north of Badhoevedorp, and the other two were to guard the Sloterweg-Spaarnwouderdwarsweg crossing.

In anticipation of capitulation, the order was given on 14th May, around 19.00, to lay down arms and abandon the defensive positions. The squadron moved back to its quarters in Badhoevedorp. After the official capitulation was signed on 15th May, the materiel was handed over to the advancing German Army

The Squadron after Capitulation

The soldiers of the 1st Squadron were first relocated to the Willem de Zwijgerkazerne in the city of Wezep, where conscripts were demobilized. After a month, the size of the units had decreased to the extent that, for registration purposes, the 1st and 2nd Squadron were combined with the two Motorized Hussars Regiments and the Mobile Artillery Corps into the 3rd Motorized Hussars Regiment, on 24th June. This marked the formal disbanding of the 1st Squadron. The Dutch Army was officially disbanded on 15th July.

In German Possession

With help of numerous photographs and scarce reports, it is possible to get a rough idea where the twelve vehicles ended up after capture. However, the photographs leave a lot of interpretation possible. As mentioned, all the L-181s were relatively worn out due to the extensive use they had seen since early 1936, so not all were suited for German re-use.

The photographs can, in general, be sorted in four categories:

- shortly after capture with Dutch markings still visible.

- with the markings removed and some non-standardized German markings applied.

- with German markings applied in a more standardized manner.

- the vehicles with German police markings.

This may indicate that, after capture, the vehicles found their way to various German units, with a small number quickly being reserved for the police, and another number going to training facilities. If any went to the front in France, like the Dutch armored cars of the German 227th Infantry Division, is possible, but not documented.

In German service, the vehicles were officially designated as Panzerspähwagen L 202 (h). The different Landsverk 180 received the same designation. At least three L-181s were used by police units on the Eastern and Balkan fronts from 1941 until 1945. Additionally, more L-181s were photographed at German training facilities, but it is hard to determine the number that were used in this role.

The six vehicles of the 3rd and 4th platoons at Schiphol had only received minor damage, with exception of one, where the roof was penetrated by enemy bullets. None were sabotaged and all were handed over to the Germans without trouble. Landsverk 606 was later seen with German forces in Utrecht, with the Dutch markings painted over. The vehicles of the 1st and 2nd platoons were mostly gathered at the Frederik Barracks in The Hague after capitulation.

German L-181s with Balkenkreuz Markings

With the Police

A small number were assigned to the German Ordnungspolizei [Eng. Order Police, abbr. Ordpo], also known as the Grüne Polizei [Eng. Green Police, after the color of their uniforms]. They originally remained in the Netherlands and once appeared in a parade, held on 10th February 1941 in Amsterdam.

The motorized Polizei Regiment Mitte [Eng. Police Regiment ‘Center’, abbr. to Pol. Rgt. Mitte] was founded in June 1941 and deployed on the Eastern Front. It had at least one platoon with three Steyr ADGZ armored cars. In July 1941, these were joined by a platoon with three L-181 M36s from the Netherlands. Each was named after a Dutch city, with known names being ‘Den Haag’ and ‘Arnheim’ [Dutch: Arnhem]. It is unknown how well these fared behind the front. The platoon was designated Panzerspähwagenzug (h) [Eng. Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle Platoon (h)], with h standing for holländisch [Eng. Dutch]. The abbreviation PzSpZug (h) was also used. Within the police regiment, these armored platoons were part of the 10. Schwerer Panzer Kompanie [Eng. 10th Heavy Armored Company, abbr. to 10. Schw. Pz.Kp].

In July 1942, the Pol. Rgt. Mitte was reformed into the newly established SS-Polizei Regiment 13. The three L-181s presumably remained in use, although one was abandoned in the winter of 1942 in Kaluga. In April 1943, the platoon was repatriated to the Polizei-Panzer-Ersatz-Abteilung [Eng. Police Armor Reserve Unit, abbr. to Pol.Panz.Ers.Abt.] in Vienna. It is unclear what happened to the vehicles afterwards. However, in late 1943, the 14. Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie [Eng. 14th Police Armored Company] was mentioned to have one platoon with three Dutch armored cars, meaning the abandoned vehicle was substituted by another L-181. The unit had been formed in October 1943 and was subordinated to the Befehlshaber der Ordnungspolizei Alpenland [Eng. Commander of the Order Police, abbr. to BdO] in Wehrkreis XVIII [Eng. 18th Military District, abbr. to WK XVIII].

The unit was based in Ljubljana and mainly active in Slovenia to protect the rear area of Army Group E. Later, the unit was reinforced to the extent that it was renamed to a verstärkte [Eng. reinforced] unit in September 1944. The three Dutch armored cars were still present by this time. By the end of April 1945, the unit was active on the frontline in southern Slovenia, but retreated to Austria in early May.

Presumably, the L-181s remained in use until the end of the war and also retreated with the unit to Austria in May. There is no public photographic evidence of them in use, but other vehicles of the unit were seen painted in Dunkelgelb with Balkenkreuz markings. The L-181s would likely have had a similar appearance, in contrast to their earlier dark paint scheme with Ordpo markings. Their fate after May 1945 is unknown.

Conclusion

The Landsverk 181 had a good design and performed reasonably well, but suffered from its lack of engine power, which hampered mobility and reduced the engine’s operational life. The L-181 saw most of its operational use by the Dutch Army in May 1940 and in Lithuania during the uprising of 1941. Deployment by the USSR appears to have been limited, but Germany used them for training and police duties well until the end of the war. They were well suited for these internal security tasks, despite their age, as demonstrated by the effectiveness as mobile air defense units on the Dutch airfields in 1940.

The distribution of the twelve Dutch L-181s that ended up in German hands is still a mystery, but the reappearance of old photographs and obscure archival references may solve some questions in the future.

The history of the L-181 is in some ways quite remarkable. Both the Netherlands and Lithuania were neutral countries and had bought the L-181 from neutral Sweden. Yet, the Lithuanian vehicles were captured by the USSR, used against Germany, and captured by Germany. Likewise, the Dutch vehicles were captured by Germany, used against the USSR, and captured by the USSR.

Landsverk 181 Specifications |

|

|---|---|

| Dimensions (lwh) | 5.56 x 2 x 2.35 m |

| Wheelbase | 3 + 0.95 m |

| Total weight | 6,500 kg |

| Tare weight | 6,000 kg |

| Payload | 500 kg |

| Crew | 4-5 [1-2 drivers, commander, gunner, machine gunner] |

| Main armament | Lithuania: 20 mm Oerlikon 1S, Netherlands: 37 mm m/34 Bofors Paw 40 |

| Secondary armament | Lithuania: 2x 8 mm Maxim, Netherlands: 2x 7.92 mm Lewis M.20 No.1 Paw., 1x 7.92 mm Lewis M.20 No.2 Paw. |

| Armor | 9 mm front, 7 mm sides and rear, 5 mm roof |

| Propulsion | Mercedes-Benz M 09 II 6-cylinder, 68 hp at 2800 rpm |

| Chassis | Mercedes-Benz Typ G 3a |

| Chassis weight | 3,200 kg with changes, 2,650 without changes |

| Max. Speed | 65 km/h |

| Min. Speed | 3.5 km/h |

| Max reverse speed | 41.5 km/h |

| Ground clearance | 25 cm |

| Turning circle | 14 m |

| Wheels | 570×160 mm |

| Slope | 40% (22°) |

| Fuel | 105-125 l |

| Range | 250-300 km |

| Production | 6 (Lithuania) + 12 (Netherlands) |

Sources

Gevechtsverslagen Mei 1940, Nationaal Instituut Militaire Historie, archieven.nl.

Handelingen Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal, 07 May 1936, p.1871-1882,

https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/0000059569.

De arbeider; socialistisch weekblad voor de provincie Groningen, jrg 46, 1936, no 6, 08-02-1936. Consulted on Delpher on 17-09-2022.

Mercedes-Benz Type G 3 (WG 09 I) & G 3 a (WG 09 II), kfzderwehrmacht.de.

German World War II Organizational Series Volume 3/V, niehorster.org.

Landsverk M38 Pantserwagen, een restauratieproject, landsverk-m38.nl.

Pansarbil L-180, landskrona.se.

Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie Mitte, Updated 7th June 2013, axishistory.com.

14. Polizei-Panzer-Kompanie, Updated 7th June 2013, axishistory.com.

Lietuvos kariuomenės šarvuočiai, plienosparnai.lt.

Dirk Starink, Schiphol als Nederlands militair vliegveld 1916-1940, pdf.

Rickard O. Lindström, Pansarbil fm/29, ointres.se.

Thorleif Olsson, Landsverk, thorleifolsson.com.

J.C. Hopperus Buma, De Ontwikkeling van de Nederlandse Gevechtswagens en Tanks tot ± 1940, Militaire Spectator.

Walter J. Spielberger, Beute-Kraftfahrzeuge und -Panzer der deutschen Wehrmacht, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, 1992 2nd edition, p.36-38.

Drs. J.A. Bom, Eskadrons Pantserwagens 1936-1940, 1986.

C.M. Schulten, J. Theil. Nederlandse Pantservoertuigen, Van Holkema & Warendorf, 1979.

J. Giesbers, A. Giesbers, R. Tas. Holland paraat! Volume 2, Giesbers Media, 2016.

Dr. L. de Jong, Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog Deel 3 Mei 1940, Staatsuitgeverij, 1970.

Georg Tessin and Norbert Kannapin, Waffen-SS und Ordnungspolizei im Kriegseinsatz 1939-1945: ein Überblick anhand der Feldpostübersicht, Biblio Verlag, 2000.

Stefano di Giusto, German Armoured Formations in the OZAK 1943-45, Tankograd 4019, Verlag Jochen Vollert.

Mindaugas Jonaitis, STRUKTŪRINIAI POKYČIAI LIETUVOS KARIUOMENĖJE 1934-1940 (STASIO RAŠTIKIO REFORMOS), 2012, pdf.

Vytautas Jokubauskas, Lietuvos kariuomenės artilerijos pabūklai 1919–1940 m., Klaipėda University.

Vyr. ltn. dr. Andriejus Stoliarovas, Lietuvos kariuomenės šarvuotieji automobiliai 1919–1940 m., pdf.

NIMH | 1 mei 1970 | pagina 355 – Tijdschriftenviewer Nederlands Militair Erfgoed (courant.nu)

NIMH | 1 januari 1954 | pagina 53 – Tijdschriftenviewer Nederlands Militair Erfgoed (courant.nu)

NIMH | 10 mei 1940 | pagina 176 – Tijdschriftenviewer Nederlands Militair Erfgoed (courant.nu)

Archival Documents thanks to Wilhelm Geijer

Ang studiebesök hos Landsverk, Kungl. Arméförvaltnings Artilleridepartements Konstruktionsavdeling, Nr. 499, Stockholm 27th April 1935.

Beschreibung des Sechsrad-Strassepanzerwagens “Landsverk 181”, Landsverk, 26th November 1934.

Special thanks to Johannes Dorn for help with identification of German photographs

2 replies on “Landsverk 181”

Interesting article. One mistake: The city of Ljubljana is the capital of present-day Slovenia, not Croatia.

Thanks for your comment!

Indeed, a silly mistake on my behalf, it has been corrected.

Kind regards, Leander