United States of America vs Grenada

United States of America vs Grenada

Grenada, the southernmost island nation in the Grenadines in the Caribbean, is a tropic island known as the spice island thanks to the harvesting of nutmeg. It had been a British colony since 1763, but in 1967, it was granted home rule on the road to independence. Grenada became a fully independent nation in 1974. Following a coup in 1979 and the new pro-Cuban government, relationships with the West began to fall apart. This was exacerbated by the construction of a large new airport facility with Cuban support at the capital, as it started to assert its political and military influence. This became a crisis at the end of 1983, which resulted in a military invasion by the United States with some support from other Caribbean islands. The invasion, expected to be quick and simple and under the justification of rescuing American citizens and restoring order, became a symbol of both the power of a newly assertive US military, just a few years after the failures of Vietnam, and also of its weaknesses in terms of organization, preparation, and coordination. The invasion is notable for both the use and lack of use of armor in support of operations.

Background and Political Crisis

This tiny island – just 349 km2 (135 sq. miles) – with a population of 110,000, had been a British colony from 1763 until it gained home rule in 1967 and full independence in 1974. The new nation and member of the British Commonwealth, under the leadership of Sir Eric Gairy, began a decline in economic terms straight afterward. Following this decline becoming a full economic crisis, Maurice Bishop seized power in an armed coup in 1979. This action and seizure of power marked a political shift to the left and closer ties with Cuba and the Soviet Union, with the new party in power: the New Joint Endeavour for Welfare, Education, and Liberation (JEWEL), which had been formed by Bishop back in March 1973 but with the coup came the end of US aid and a collision course between the USA and Grenada was set.

Source: worldatlas.com

Progressively, the party, renamed as the ‘New Jewel Movement’ (NJM), removed democratic limitations and replaced them with a more Marxist-leaning government. This included removing the influence of the Governor-General, Sir Paul Scoon. Seeking to change the direction of the island nation, Bishop sought ties outside of the nation’s traditional influencers, like the United States and the United Kingdom, and instead moved to embrace Cuba, the Soviet Union, and even to a lesser extent, pariah states like Libya and North Korea.

Source: repeatingislands.com

Construction of the airport with two runways, each measuring 2,743 m long and 45 m wide, at Port Salinas began in the late 1970s, with around 600 Cuban construction workers being sent to help with the building, which was in two phases. Phase 1 was an initial 1,700 m foot long segment which, due to delays, was not going to be finished until the end of January 1982. This would be followed by the extension phase to make it a full 2,743 m long and could take an additional couple of years.

According to Grenada, this runway was for tourism and economic development purposes. This would be backed up by the funding sources, which, contrary to media reports at the time of the investigation, was not solely a Cuban venture. The Cubans, in fact, were to supply just US$10 m worth of labor and material (22% of the total cost) over a 3 year initial construction period for the runway and the terminal resort which was planned. Venezuela (about 160 km to the southwest) was funding the project to the tune of US$500,000 worth of labor and was also to supply the diesel fuel for construction, as well as petrol and asphalt. Financing from the Middle East was also speculated as a source of loans, as attempts to obtain money for it from Europe and Canada had failed. It is known that the PRC had managed to obtain US$20 m in loans from the IMF. Certainly, this was no clandestine project, especially when you consider the British agreed to underwrite a loan to Grenada totaling GBP£6 m for the purchase of electronic systems from Plessey for the airport. This would also be the second major landing strip on the island, as there was an existing one at Pearls, measuring some 1,524 m long. Pearls was about 25 km to the northeast of St. George’s, so the development of a new runway for the capital was clearly going to be useful for the economic development of the island, as well as whatever military use it might be seen as offering. It would also be much larger than the one at Pearls – long enough to allow landings by planes such as the Boeing 747-400, which needed around 1,880 m to land and stop safely.

American military analysts were less inclined to the tourism explanation and determined that it would also potentially allow MiG 23s fighters to operate from there, as well as extending the range of Cuban fighter-bombers across the whole Caribbean. Geo-politically, it could also potentially serve as a base for supporting Soviet influence in Central America and Cuban influence in Africa, as it was some 2,575 km closer to Angola than Havana. In 1980, Bishop signed a mutual aid assistance agreement with the Soviets, which did indeed give them landing rights at this airfield for their long-range surveillance aircraft.

Source: US Department of Defense

It is not hard to imagine that, regardless of the original purpose of the runway, it could be used by larger aircraft and potentially changed the balance of power in the region. Cuban ulterior motives would not be hard to justify, given the influence of the Cuban regime on Bishop’s Government, although it would be wrong to suggest that Bishop was a stooge planted by Cuba. The Cubans did not even recognize Bishop’s leadership for a month after he took power (14th April) by which time the UK and the United States had already done so (20th March 1979).

Funding and technical assistance for the radio were not, however, Cuban – it was Soviet in the form of two technical advisors and funding, on top of the very modest financial gift of US$1.1 m in agricultural and construction equipment and vehicles. The Soviets were no doubt pleased with the leftist drift of Grenada, but let Cuba exercise its own sphere of influence rather than become directly embroiled.

Despite this leftist shift and the engagement with Cuba, Grenada was, however, no Marxist or isolationist state. Indeed, the foreign ownership of property was still permitted and many US citizens, in particular, had houses or land there. The Medical School at Saint George’s University was specifically run for and paid for by US citizens. Thus the Grenadian revolution can be seen as more ‘anti-imperialism’ than ‘anti-American’ or ‘anti-western’.

Source: Google Earth

Probably the most obvious example of Cuban influence was the construction of a new 75 kW AM radio transmitter and mediumwave tower capable of broadcasting across the whole island as well as to neighboring islands, under the name Radio Free Grenada (15.104 and 15.945 kHz). This replaced the old Windward Islands Broadcasting Service (WIBS). This was seen as a counter to the Americans building a broadcasting station for Voice of America on the island of Antigua, some 550 km away to the north.

Source: cawarstudies via Raines

Radio Free Grenada had the range to be able to be detected all across the Caribbean and there survives a 6-minute 36-second recording from them made in January 1980 which was picked up in Louisville, Kentucky – a distance of 3,758 km.

https://shortwavearchive.com/archive/radio-free-grenada-january-1980

This is not to say that the USA was openly hostile to Grenada either, far from it – Bishop had actually been personally received in Washington D.C. in June that year and met by the US National Security Advisor William Clark. The situation was, however, awkward and a hawkish vehemently anti-communist President Reagan meant that the situation could easily cross a tipping point into a less cordial relationship. Grenada was a problem and was being monitored but there was no clear course of action to follow.

This tense geopolitical balancing act started to fall apart through the summer of 1983, resulting in a power-sharing agreement between Bishop and the more radical former Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard. It fell to pieces on 12th October, when Coard deposed Bishop and placed him under house arrest, only for Bishop to be freed by his own supporters a week later and take up residence at Fort George (renamed Fort Rupert in 1979 and now renamed, once more, as Fort George).

Source: GrenadaConnection.com

General Hudson Austin, Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of Grenada and a backer of Coard, sent at least 3 BTR-60PB armored personnel carriers to Fort Rupert on the 19th. There, Austin’s troops recaptured Bishop, and summarily executed him along with several of his cabinet ministers for good measure, removing a major potential challenge to leadership on the island. Perhaps buoyed by the newfound power, Austin sought to consolidate it for himself rather than Coard. Both Coard and Austin marked a shift towards Marxism and further into the sphere of influence of Cuba in the minds of the Americans. Whilst Coard and Austin may also have sought this attention and closer relationship, the Cubans were at best unhappy with this state of affairs, as they could clearly see it might provoke a US response and leave them in a difficult political position.

Source: airspacehistorian via Seabury and McDougall

General Austin proceeded to dissolve the civilian government and implement a Revolutionary Military Council, with himself as spokesman and de facto head of state. With the airport closed to all departures and arrivals, and a 24-hour curfew put in place for a 4 day period, Austin had managed to impose not only a coup but also martial law in very little time and with little difficulty. He was to rule Grenada for just 6 days.

“Let it be clearly understood that the Revolutionary Armed Forces will govern with absolute strictness. Anyone who seeks to demonstrate or disturb the peace will be shot. An all-day and all-night curfew will be established for the next four days. From now until next Monday at 6:00 p.m. No one is to leave their house. Anyone violating this curfew will be shot on sight. All schools are closed and all workplaces except for the essential services until further notice.”

Curfew broadcast from Radio Free Grenada by

General Hudson Austin, 2110 hours 19th October 1983

Source: airspacehistorian.wordpress.com via AP Newsarchive

https://airspacehistorian.wordpress.com/2018/07/

In doing so, he made a fundamental error and managed to ‘trap’ around 600 US medical students who were attending St. George’s School of Medicine, as well as around 400 US citizens on the island. This lockdown was therefore used as a convenient casus belli by the Reagan administration to invade, remove the Marxist government and restore a democratic one that would be friendly and receptive to the interests of the United States. All this was to be done with none of the legal hurdles of an embargo or UN Resolution. As a matter of political convenience then, this ‘rescue’ would also establish the dominance of American, and to a lesser extent, other Caribbean-nation interests’ in the area. It should also be noted that the lockdown was not in place for long and was lifted at 0600 hours on 24th October, with flights out of Pearls resuming. It was also brought to the attention of the US Embassy in Barbados that only around half of the students in Grenada wanted to leave and, as far as can be ascertained, no efforts or approaches whatsoever were made to evacuate them peacefully.

It was not, however, despite the alleged threats towards these US citizens, enough impetus to actually plan for military intervention for several more days, with the initiation of the plan of 17th October followed by a Warning Order from the Joint Chiefs on 19th October. Planning for a military operation to evacuate citizens was specifically ordered by President Reagan on the 21st but may have started earlier with some preliminary ideas of a military resolution.

It has to be noted that this sudden urgency and the seemingly disorganized response was in contrast to the fact that, just two years prior (August 1981), USLANTCOM (United States Atlantic Command) had conducted large-scale joint operations exercises on exactly this scenario, with Marines and Rangers leading an invasion of a Caribbean island to rescue US citizens. Yet, as will be seen, few, if any, lessons had been drawn from that major exercise and the actual deployment to Grenada was a mess marred with accidents and confusion.

Intelligence Failure, Legal Legitimacy, and the Prelude to Invasion

Post-1979, military and intelligence cooperation with the USA or its allies, like Great Britain, by Grenada had effectively ended, leaving a vacuum in which the island’s invasion had to be planned at short notice. Even so, as previously noted, this was as much through a lack of effort and foresight as it was just a matter of a short time span in which to do it. The construction of the airfield at Point Salinas was hardly a surprise or even a secret and the islands were close enough and had been Allied under the British for long enough there was no excuse for a lack of maps of the place.

In fact, when the US military invaded, the best available map was on the USS Guam and was itself based on an even more ancient 1896 nautical chart. As bad as going to war on the back of a century old map was, there was not even the opportunity to make good copies of it, as the only copier onboard the USS Guam was not good enough to copy it. Thus, the invasion took place with grossly inadequate maps, such was the rush and shambles in which the operation was cobbled together. Delta forces were slightly better off, as they had some Michelin tourist maps of the Windward Islands at hand – ideal maybe for knowing where to get a good lobster en croûte, but not so much for a military assault or a reconnaissance by special forces.

On top of that inadequacy, there was not even to be a joint on-ground command. Vice Admiral Metcalf would command the operation from the safety of the USS Guam, with the separate Army (Ranger) and Navy (Marine) forces reporting directly to him. Neither force was to support the other logistically and neither would share supplies without confirmation of reimbursement for the cost of the supplies shared because service boundaries were more important in a pointless turf-war between services than a shared objective. Vice Admiral Metcalf’s suggestion on the 24th (the day before the invasion) of placing General Schwarzkopf on the ground to command forces was overruled by Admiral McDonald back in Virginia, on the basis that Major General Ed Trobaugh of the 82nd Airborne was senior. This decision guaranteed that, at least for the opening stages, there would be no single dedicated commander on the ground.

As well as the lack of geographic information, there was also an unclear idea of the armed forces against which they may have to fight. Estimates of Grenadian opposition put the number at around 1,000 to 1,200 regular troops of the People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA) under General Hudson Austin. On top of this were up to 2,400 members of the People’s Revolutionary Militia (PRM) under Winston Bullen (who was also the manager of the Grenada Electricity Company, known as Grenlec) although this was believed to have been largely disarmed and disbanded by the PRA, with Bullen executed when Austin seized control. The bulk of weapons were in those two forces, including modern small arms, like AK 47s, and the BTR-60 and BRDM-2 armored vehicles, although the militia, in particular, were a loose and irregular force which could also be seen using .303 caliber WW2-era bolt action British Enfield rifles.

Source: Revolutionary Govt. of Grenada.

A 300-500 strong Grenada Police service (GPS) was also available, under Major Ian St. Bernard, although these were not combat troops and included the Coast Guard, Immigration, and Prison Services. Total naval forces were minimal, with just four torpedo boats and there was no combat air force or even a radar on the island. The armored vehicle assets available to the PRA were tiny – just 6* Soviet BTR-60 armored personnel carriers, a pair of BRDM-2 armored cars delivered from the Soviet Union in 1981-1982, and no tanks at all.

(* A US intelligence survey post-war says 7, but only 6 can be accounted for)

The BTR-60PB was an 8 wheeled armored personnel carrier with distinctive pointed front and sloping sides. Amphibious, simple, and cheap, the vehicle has been widely exported and used since it was first designed in the 1950s. At just 10 tonnes, the vehicle could carry up to 12 men (2 crew and 10 troops) to battle and then support them by use of a single 14.5 mm KPVT machine gun and a 7.62 mm machine gun. The vehicle was proof against small arms fire up to heavy machine gun caliber thanks to between 5 mm (floor) and 10 mm (turret front) of fully welded steel armor. Powered by a pair of GAZ-40P 6-cylinder petrol engines delivering 90 hp each (180 hp total), the vehicle could attain a speed of up to 80 km/h on a road, meaning it could rapidly deploy from one place to another, providing flexibility for a relatively lightly equipped force.

The BRDM-2 was another amphibious, light, and highly mobile armored vehicle from the Soviet Union. Designed back in the 1950s and built in the 1960s, the vehicle was still, despite its age, a serious threat to troops, especially those without anti-armor weapons. Armed with the same 14.5 mm KPTV machine gun and a 7.62 mm machine gun in a small frustoconical turret like the BTR-60PB, the BRDM was a smaller vehicle with just four wheels and a crew of 4. With armor up to 14 mm thick, the BRDM-2 was also fully protected against small arms up to heavy machine gun fire and shared the same major benefits of the BTR-60PB – namely, it was cheap, simple, and effective. It was also highly mobile courtesy of a single V8 petrol engine delivering 140 hp, allowing the vehicle to reach a somewhat dangerous 95 km/h on a road.

Of note in the assessment of the strength of Grenadian forces is that, although the US Joint Chiefs’ report mentioned 6 BTR-60s, SIPRI records deliveries of 12 such vehicles, and the CIA say in one report 6, and in another 8 BTR-60s, along with two BRDM armored cars. The CIA also notes that an agreement signed in 1981 included deliveries scheduled between 1982 to 1985 that would bring an additional 50 APCs. Their analysis of captured documents after the 1983 invasion revealed eventual plans to have sufficient small arms for theoretically arming up to 10,000 men, although, in practice, this would only be adequate to field a force of around 5,000 and 60 APCs and patrol vehicles. As far as aircraft went, just one plane was known and this was to be a Soviet AN-26 to haul up to 39 paratroopers, although the AN-26 found after the invasion was in the civilian colors of a Cuban airline.

As far as heavy weapons or air defense were concerned, the forces were primarily the Soviet-supplied ZU-23-2 mm anti-aircraft guns. All of these vehicles and weapons were believed at the time of invasion to be centered around the airfield at Port Salinas.

With a range of up to 2.5 km and capable of delivering 400 rounds per minute, these were not to be underestimated, especially as a threat to low flying aircraft. Admiral McDonald, in what was to be a demonstration of hubris on the part of American planners, described the forces on Grenada as a “third rate, lightly armed and poorly trained adversary”, a comment which contradicted his own claim of “well trained professional” Cuban troops being present, and thereby underscoring that his claim was without evidence or merit.

The status of Cubans on the island was unclear, with two vessels, including the freighter Vietnam Heroica (which had delivered 500 tonnes of cement for the airport project), around 600 workers, and an unknown quantity of arms. The other ‘Cuban’ ship was the Kranaos, which was actually a Panamanian vessel chartered by the Cuban Government. It is clear from the intelligence analysis that, whilst the presence of these 600 workers and some arms of an unknown type was known, these were not the Cuban ‘threat’. Instead, the intelligence analysis provides for a threat of up to 250 armed Cubans who might have been possibly delivered by the Vietnam Heroica, although there was no evidence to support this rather tenuous supposition other than that this ship had been implicated in bringing Cuban forces to Angola in late 1975.

A CIA analysis of Grenadian opposition forces clearly lists some 350 construction workers, 25 medical personnel, 15 diplomats, and just 10-12 military advisors, for a total of just 400 Cubans, although this did not include the unknown numbers of the Vietnam Heroica, which was estimated at just an additional 200.

Either way, fewer than 2,000 enemy regular forces, and a few more irregular forces, effectively no navy, no air force, and some miscellaneous armored vehicles was hardly a military of par with the vast array of forces at the disposal of the United States. Admiral McDonald’s assertion of 1,100 ”well-trained professional” Cuban soldiers on the island was just utterly false. Later, US intelligence based on interviews with prisoners would show just 43 of them were even members of the Cuban armed forces, but that a dozen or more may have been ‘advisors’. The intelligence added that up to 50 Cuban military advisors might have been present too. In a taste of just how little Cuban opposition there really was, the most senior Cuban present was Colonel Pedro Comas who would only arrive on 24th October and begin plans to defend southern Grenada from the incoming American forces. He had achieved little more than some sandbagging by the time the Rangers confronted him the next day.

Even by this time, with active military planning for an invasion based on not much more than speculation and grand political machinations underway, the United States was still engaging with this military government. On 21st October, in fact, Donald Cruz, the US Consular Officer for Barbados, went to Grenada to meet with Major Leon Cornwall, the Head of the Revolutionary Military Council and President Reagan signed National Security Directive 110 ordering the US military to explore options for evacuating US citizens from the island.

At Bridgetown, Barbados, there was an emergency session of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) convened to try and bring stability to Grenada and the first substantial legal justification for going beyond the rescue of US citizens was established in the form of a vote on Article 8 of the OECS Collective Security Treaty 1981. Grenada was actually a member state of the OECS. The OECS were now looking at the island as being ruled by an ‘outlaw regime’ that needed to be removed calling for the restoration of order and democracy. The actual request, was, despite being drafted not by the OECS but by the American State Department, open to some questions about its validity, especially as it violated the principle of OECS members not taking action without unanimous consent – something unlikely to be agreed to by Grenada. Here, the members asked Barbados, Jamaica, and the United States (not members of OECS) to send a peacekeeping expedition to Grenada. This was followed a few hours later, in the early hours of 22nd October, by Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon asking for help in the form of a peacekeeping force to restore order and security. Implicit within that request would be the removal of the Revolutionary Military Council in Grenada although this was made clear in a TV interview aired on 31st October that year (after the invasion) Sir Paul Scoon clarified that whilst he specifically felt that only an invasion could remove the government that he asked not for an invasion but for outside help from OECS and the USA as well.

These two elements were not the end of the legality issue for the invasion. Grenada was part of the British Commonwealth, meaning any military incursion should at a minimum take place with the approval of the British. Further, under Article 51 of the UN Charter and Article 5 of the Rio Treaty, the United States would have to inform the UN Security Council of the reasons for the operation to justify it. The consultation with the British did take place, sort of. On 22nd October, a phone call was made between President Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher, no doubt with an eye on the successful British recapture of the Falklands after an Argentinian invasion, was well versed in just how complex an invasion was going to be and the potential for a great loss of civilian and military lives. From a political perspective too, had it gone horribly wrong, it would have caused serious damage to Western prestige as well as both political and military deterrence against the ongoing Soviet threat in Western Europe and beyond. On the other hand – a well-executed and swift American intervention with little loss of life would show the world America’s military prowess and capabilities, building not only confidence in US political decision making but also the ability of the military as a counter-force to the Soviets. Unknown to Thatcher was that, well before their phone call, Reagan had already given permission for the invasion to commence, rendering Thatcher’s concerns roundly ignored as even at this late stage military intervention could have been canceled.

Preparations of an Invasion Force

Two basic plans were developed for how to take Grenada, based on limited information, whilst further intelligence operations were being prepared hastily in the form of reconnaissance flights from SR-71 Blackbird and the TR-1 (U2) spy planes, as the CIA had no assets on the island. As it turned out, no data from those surveillance flights found its way to the assault force in time for the opening of hostilities. Planning was left to Combined Joint Task Force 120 (CJTF 120) under the command of Vice-Admiral Metcalf and he had been given less than 2 days to make his plans and initiate them. His deputy was Major General Herman Norman Schwarzkopf, later to be famous as the leader of Coalition Forces during the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

Vice-Admiral Joseph Metcalf (left) and General Schwarzkopf (right). Source: wiki

The first of the two plans, ‘Plan A’, called for five C-130 Hercules aircraft to parachute drop JSOC (Joint Special Operations Command) teams during the hours of darkness at Point Salinas and at Pearls. Fire support for the landing would come in the form of 4 AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships.

After capturing Point Salinas airfield, the plan was to move 6.5 km up the coast to St. George’s and capture the radio station and police headquarters. After that, another 6.5 km hop to capture the barracks at Calivigny. With the airfield, radio station, police HQ, and army barracks taken, 16 C-130 Hercules would then deliver the 1st and 2nd Ranger battalions at Point Salinas and Pearl to consolidate the ground and disperse any remaining enemy forces. This whole plan was somewhat optimistically estimated to take just 4 ½ hours.

The second option, ‘Plan B’, relied upon an amphibious assault combined with helicopter incursion of US Marines, followed by Rangers on beaches by Point Salinas and Pearl, which had already been scouted by teams of SEALs several hours earlier. This would be followed by a battalion of troops being landed either at the beach or at Point Salinas airfield, from where they could move to St. George’s School of Medicine and Grand Anse beach. From the beach, the Marines would then seize Calivigny Barracks. After these first two phases, a further force of Rangers would then be landed at Point Salinas and advance on the police HQ and Army HQ.

Plan A would take longer to put into place than plan B by several hours, but both plans came with the risk that, once they began, the students might be killed or taken hostage in retaliation.

Support for American forces would be provided in the form of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), which would provide small contingents from Jamaica and Barbados. OECS had only been around for two years (formed 1981) and was a partnership of Dominica, St. Lucia, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, Antigua, Barbados, St. Vincent, and the Grenadines as a bulwark against the spread of Marxism in the Caribbean.

The Jamaican Defence Force (JDF) contribution consisted of a single rifle company, an 81 mm mortar section, and a medical section, amounting to a total of around 150 troops. The Barbados Defence Force (BDF) contribution consisted of a single rifle platoon of around 50 men.

Source: wiki

As well as those local forces, an additional force of 100 constabularies (police) was to be sent by the OECS Regional Security Unit to help establish law and order. These three forces were to be used in their entirety in the securing of Richmond Hill Prison, Radio Free Grenada, the police headquarters, and Government House after US forces had secured them from Grenadian forces.

Secrecy

An invasion with such little preparation time and information was reliant on absolute secrecy. This need for secrecy utterly failed, as not only did the Cubans and Grenadians anticipate that some US action might be considered, but also the movement of US warships into the region was also reported in the media. This was despite the Joint Chiefs of Staff imposing a ‘SPECAT’ order (a special category of secrecy to avoid alerting the Grenadians to the plan). While the Americans immediately failed to keep this a secret, the exact nature of what they were planning would not be known – nonetheless, this put the locals on alert and this would later result in US casualties.

The Go

As forces started to move towards the region and plans were being finalized, the provisional order to initiate the invasion came on 22nd October 1983. This was to deploy a force of Marines, Rangers, and Airborne Troops, with the date set as 25th October, although it is important to note that this does not mean that an invasion was certain. Those three days were necessary to get the logistics and coordination in place for the operation to be conducted and at any time until then, the whole thing could be called off.

Plan A was the method selected for the invasion, with the battlegroup led by the USS Independence (out of Virginia) and Marine Amphibious Ready Group 1-84 (MARG 1-84) out of North Carolina. MARG 1-84 had been on its way by sea to Lebanon to replace the Marines of MARG 2-83 in Beirut when it was diverted to Grenada.

These two groups would launch their forces from 102 km (55 nautical miles) NW and 74 km (40 nautical miles) north off the coast of Grenada, respectively. Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) teams and Rangers would leave from Pope Air Force Base in North Carolina and Hunter Army Airfield in Georgia six hours beforehand. Before dawn on 25th October, these JSOC troops would attack the Grenadan police and military buildings around St. George’s and then advance quickly upon the Governor’s Residence to protect him.

Rangers and Marines would then be landed at Point Salinas and Pearl respectively. Men from 82nd Airborne Division would remain on alert at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in case they were needed. The whole island was effectively bifurcated into operational zones, with the north being allocated to the Marines and the south to the Army.

After achieving their goals and evacuating the citizens, a peacekeeping force of 300 men from Jamaica and Barbados would be airlifted to Grenada to work with the Governor-General on a new interim government. That was the plan.

Air support for the operation would be provided by the US Air Force in the form of 8 F-15s from 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing and 4 E-3A Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft from 552nd Airborne Warning and Control System detachment. These air forces would be protection for the task force on the remote chance of some outside interference being attempted by air.

23rd October

The order was on the 22nd, with the invasion set for the 25th. However, the next day, the 23rd, there was a disaster for the US Marines, not in the Caribbean, but in Beirut. The US Marine Corps barracks at Beirut Airport was targeted by a suicide bomber driving a truck, who plowed through the gate of the barracks and detonated a huge bomb that killed 241 American troops. Political analysis of this time connects the terrible events in Beirut as a bloody nose for America to the ‘distraction’ offered by success in Grenada for the forthcoming US Presidential elections in 1984. Certainly, the Grenada crisis provided some political relief for Reagan and was used to downplay the deaths in Lebanon during the subsequent elections.

In the immediate aftermath of this bombing, Secretary of State for Defense, Casper Weinberger, gave full power to General Vessey (Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) to invade Grenada. Gen. Vessey was a highly regarded and experienced officer who had seen combat both in World War II and in Vietnam.

24th October

With the go-order setting an invasion to start on the 25th, two C-130s dropped four-man US Navy SEAL teams off Point Salinas and Pearls to prepare for the landings. This was not a success. Firstly, the beach at Pearls was found to be unsuitable for an amphibious landing by the Marines, meaning they would have to come in by helicopter instead. Second, the first casualties for the US took place when four men of the 11-man SEAL team were lost in the rough seas off Port Salinas.

Initiation – 25th October 1983

The early hours of 25th October 1983 were to begin with a coordinated assault on the airstrips at Point Salinas and at Pearls. Before dawn that day, a 35-man Delta-force team had been landed at Point Salinas with a plan to clear the runway for the Rangers – it had been blocked with vehicles and boulders. This Delta force team was discovered due to the alertness of the Cubans and immediately pinned down by them. The result was that there would be no easy opportunity to land C-130’s. It would be four hours before the Rangers arrival turned this situation around.

C-130’s from Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia, were to drop the lead elements of the invasion force from the sky. However, this plan started with the failure of the onboard navigation system, meaning the following aircraft had to have their course adjusted, delaying deployment by parachute of the Rangers at Point Salinas by 36 minutes.

No joint invasion could therefore happen, as the Marines at Pearls arrived first, hitting Pearls from helicopters at 0500 hours. Thus, the loss of tactical and strategic surprise had been achieved. The famous maxim attributed to Helmuth von Moltke the Edler (1800-1891) is phrased as ‘no plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first contact with the main hostile force’ – the plan was going wrong already.

Source: USMC

With the delayed arrival of forces at Point Salinas, the first combat contact by other than special forces was made by the Marines at Pearls. The opposition, however, was token at best, in the form of ineffective fire from 12.7 mm anti-aircraft guns, which were quickly eliminated by the supporting AH-1 Cobra gunships. With that out of the way, the Marines moved unhindered to Grenville, where they occupied the town.

Source: US National Archives.

Source: US National Archives

The Marines spent a total of just two hours achieving a total initial success for their part in the opening phase. The only small wrinkles in the whole affair for the Marines had been two Marines injured and a Jeep fitted with a TOW anti-tank guided missile system damaged during the unloading from the CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters rather than enemy action.

Source: US National Archives

The Marines were fine, the Rangers were delayed and special operations were not going according to plan. Another SEAL-team raid, this time to capture the key location of the transmitter of Radio Free Grenada, also skirted with disaster. Two 6-man SEAL teams inserted by MH-60 Pavehawk helicopters, which landed in a nearby field, managed to capture the radio station, only to find that the local forces wanted it back. The PRA sent at least one BRDM-2 armored car and a number of men to recapture the transmitter. The result was a lengthy firefight in which the SEALs held off the Grenadian forces despite many of them being injured. They had to withdraw, as they lacked ammunition and any anti-tank weapons.

Unable to communicate with their own support due to their radios not working, they escaped to the ocean and tried to steal a boat before finally managing to be rescued to the USS Caron.

Once more, a special forces operation had nearly lost the Americans a significant number of men and could have handed a media or political victory to the Grenadians and Cubans. The radio station had been crippled by the SEALs cutting the wires when they left, but also now had to be destroyed by naval and helicopter gunfire, meaning that it could not now be used, as per the original plan, to broadcast the good news of the ‘liberation’. As it was, there was damage caused to the building, but it was not leveled by bombing, although it had been rendered unserviceable. This meant that a new broadcast system would have to be employed.

The special forces attack on the strategic location at Richmond Hill Prison was even worse. Five Black Hawk helicopters moving on the hill carrying troops from B Squadron Delta force and C Company Rangers from 1st Battalion came under fire from machine guns and 23 mm anti-aircraft guns based at Fort Frederick. The result was numerous hits on the aircraft and numerous injuries, although, incredibly, on the way in, no one was killed. Dropped at the prison, the special forces found it had been abandoned and the raid was aborted. Having watched the helicopters come in and now leave, the anti-aircraft gunners at Fort Frederick continued to fire on them and the luck of the men ran out when one helicopter was hit in the cockpit by a 23 mm shell, killing the pilot and leaving the helicopter to have to crash land. The other four helicopters made it back to the fleet with damage, which meant, in one case, an emergency landing. The crashed Black Hawk needed a rescue mission to recover the men stranded when it went down.

With the parachute drop at Point Salinas delayed, the drop ended up being carried out in the light of the dawn, with delivery at 0536 hours. Anti-aircraft and automatic weapons fire greeted them and the Joint Chief’s report also claims that there was anti-aircraft fire against C-130s approaching Point Salinas from Cuban forces on the ground. Quite how this could be identified between Grenadians and Cubans on the ground at the time by a C-130 crew is unclear and seems to fall prey to the ‘need’ to identify as much opposition as possible as being ‘Cubans’ rather than any practical or effective military determination. Regardless of whether it was a Cuban-fired bullet or a Grenadian-fired one, the fire was equally deadly and the loss of even a single C-130 could have resulted in a total disaster for the American forces.

However, the result of that fire from the ground was that some of the Rangers were deployed by parachutes at just 500 feet (152 m). Whilst dangerously low, this decision did prevent the loss of a C-130, as it put them below the anti-aircraft guns which had been positioned on the hills around the airport. With Rangers on the ground, a firefight now ensued between them and the Cubans and Grenadians at the airfield.

As more troops were being dropped or attempted to drop, they were now out of sequence and those who did land, did so all over each other, leading to total disarray on the ground. Here, where they were most vulnerable, and a total shambles thanks to the initial confusion being compounded, they could have been overrun or shot to pieces strung out on open ground. Just 40 men were on the ground instead of the hundreds intended. C-130s were having to turn away to avoid fire and unable to amass the force required, those few men were in a difficult position.

The salvage of this debacle was only due to the judicious use of AC-130 gunships (1st Special Operations Wing USAF) providing fire support from above and a charge by the men almost at bayonet point to overwhelm the defenders narrowly averted a disaster. Instead of that disaster, the result was the capture of the airport, the end of opposition there, and the taking of around 150 prisoners, a number of arms, and a single BTR-60PB.

Source: airspacehistorian via Trujilo

With the airport finally in their hands, the Rangers set about trying to clear some of the debris, commandeering one of the bulldozers on what was still a building site. This incident was later conflated in the movie ‘Heartbreak Ridge’ (1986) to be where the bulldozer was turned into a ‘tank’ to run down Cuban positions.

Soviet-supplied construction equipment found at Port Salinas airport.

Source: US National Archives

Despite being primarily construction workers and not regular forces, the resistance these Cubans put up was actually taken by the US Joint Chiefs as a sign that a significant Cuban combat force was actually present on the island – a lie later to be reinforced by the rather cheesy 1986 Clint Eastwood movie ‘Heartbreak Ridge’. Photographic evidence shows at least a few Cubans in military uniform and the CIA post-invasion assessment of actual ‘troops’ put the total at less than 50 – about what you could expect as a security force for the construction project. Later searches of the airfield found a warehouse with a stock of arms and ammunition. A lot of press attention was directed at these supplies as the ‘evidence’ of a significant build-up of Cubans to help justify the invasion post-fact. Given the huge political interest by the US administration taken in photographing these supplies, it is noteworthy how few photographs exist of uniformed Cuban troops.

As 2nd Battalion arrived after 0700 hours, two men were killed in the jump, another seriously injured, and a fourth tangled up in the harness and stuck on the plane. With reinforcements, the Rangers moved out from the airport towards Calliste, where strong resistance was met. After yet another lengthy gunfight, one Ranger was dead and 75 more prisoners were taken.

Source: US National Archives.

Source: US National Archives

By 0730 hours, the first Rangers of A Company, 1st Battalion reached the True Blue Campus next to the airfield and had another firefight with the PRA. Using M151 Jeeps fitted with M60 machine guns as their reconnaissance vehicle, the Rangers were ambushed by PRA forces, leaving three Rangers dead.

Source: US National Archives

Source: Surfacezero.com on Pintrest

It was not until 0900 hours that True Blue Campus was cleared and 138 of the American students located and secured. At this time, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were digesting the stubbornness of the Cubans at Port Salinas and had decided they needed more men. Thus, two battalions of the 82nd Airborne, amounting to 1,500 men, who had been on standby, were ordered to the island. They embarked on their airlift at 1000 hours.

This was the correct decision, as it was rapidly becoming clear that the Grenadian and Cuban forces present were putting up a far stiffer resistance across the board than first thought during the planning stage. This decision would be reinforced by the fact that Rangers from B Company, who were to be landed at Fort Rupert to take and hold that location, had to turn back due to the ferocity of enemy anti-aircraft fire.

It would be surprising perhaps to the American planners that their caution after initial over-confidence was well justified. The men from 2nd Battalion, 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne had started to arrive just after 1400 hours and, just over an hour later, at 1530 hours, they were sorely needed to support the Rangers.

Two views of the same motorcycle and sidecar combination found at Port Salinas airfield and serving as a photo backdrop for two US Air Force Photographers to pose in front of members of the 82nd Airborne

Here, a PRA counterattack had to be repulsed as they attempted to reclaim the airport. Supported by an unknown number of soldiers, three BTR-60PBs engaged the perimeter, which was being held by Rangers of 2nd Platoon, A Company. The value of bringing anti-tank equipment was made self-evident, as the Rangers engaged these vehicles with Dragon ATGMs, 66 mm LAWs, small arms, and grenades.

Two of the three BTR-60PBs stopped by the Rangers. Hits from the 66 mm LAW and a 90 mm recoilless rifle on these vehicles were reported, although the location of the hits cannot be determined nor is there evidence of burning.

Source: US National Archives

With two of the PRA vehicles knocked out or otherwise crippled and casualties taken as they unsuccessfully tried to break the American line, the PRA forces withdrew. The third BTR was then caught in the open by an AC-130 gunship and taken out by 105 mm gunfire.

The third BTR-60 PB caught in the open and preyed on by the 105 mm gun on the AC-130. The vehicle moved slightly between these shots, possibly as the result of the attempted recovery. Source: airandspacehistorian.com and Pintrest respectively.

After repulsing that attack, the airport was finally under the complete control of US forces. Whilst it had not been an easy task, it had been completed as a result primarily of the fighting abilities of the US troops, rather than the original plan for that location, which had exposed them to so much risk. Whilst that had finally worked out, things were not going so well elsewhere.

The SEALs who were part of the rescue team for Sir Paul Scoon had got to Government House, where he was being held under house arrest, and their mission nearly ended. One of the Black Hawk helicopters hovering whilst the SEALs rappelled down was struck by ground fire, which hit the pilot. He was seriously wounded but the helicopter did not crash. Once more, the loss of a helicopter at a critical juncture in the operation was narrowly averted. On the ground, the 15-man SEAL team managed to overcome the guards, but then could not leave with Sir Paul Scoon, as their presence had been detected and BTR-60 APCs had arrived and opened fire on them.

Unable to tackle even this light enemy armor, the SEALS became trapped and were in serious danger of being overwhelmed. With the Rangers unable to rescue them, combat air sorties by AH-1 Sea Cobra helicopter gunships and an AC-130 Spectre gunship were used to support the SEALs until help could arrive. Outside Government House, one BTR-60PB was taken out by 40 mm fire from an AC-130 gunship, which set the vehicle on fire.

Two views of the BTR-60PB knocked out by Government House due to fire from an AC-130. Source: Mike Stelzel and Pintrest respectively.

Grenadian resistance was continuing and heavy anti-aircraft fire was being received from Fort Frederick and Fort Rupert. One of the AH-1 helicopters conducting fire support over St. George’s was struck by this fire and crashed into a football field near the shore, causing the death of the copilot and seriously injuring the pilot. A helicopter rescue was then initiated using a CH-46, with an AH-1 gunship as protection, AA fire struck that second AH-1, sending it crashing into the harbor, killing both the pilot and copilot.

Fort Frederick, an old British Fort overlooking the harbor, was well situated and dominated the area. Further helicopter air operations were just far too dangerous and an airstrike against the anti-aircraft positions was ordered by Vice-Admiral Metcalf. There was a known risk of civilian casualties in doing so, but it was deemed necessary and carried out by Navy A-7 Corsairs launched from the USS Independence.

The goal was to reduce the anti-aircraft fire and also take out what was believed to be a military command post. Lacking maps and any ground indication of the target, those Corsairs managed to bomb a mental hospital at Fort Frederick at 1535 hours. Eighteen patients died in the attack.

The American plan was going horribly wrong, as the ‘third rate’ military force in Grenada was proving stubborn and the Cuban construction workers were being diagnosed as being a battalion in strength, such was their resistance. Resistance was fierce and sporadic and casualties, both Americans and civilians, were now rising. On top of that, only 138 medical students had been found. It was realized that 200 more were on the campus at Grand Anse. By noon that day, troops had reached the True Blue Campus but not located the students.

The Marines, having been a victim of their own success, were thus retasked with a landing at Grand Mal Bay north of St. George’s to outflank the Grenadian forces and to draw them out of the city, in an effort to bring the invasion to an end and also to rescue the trapped SEALs.

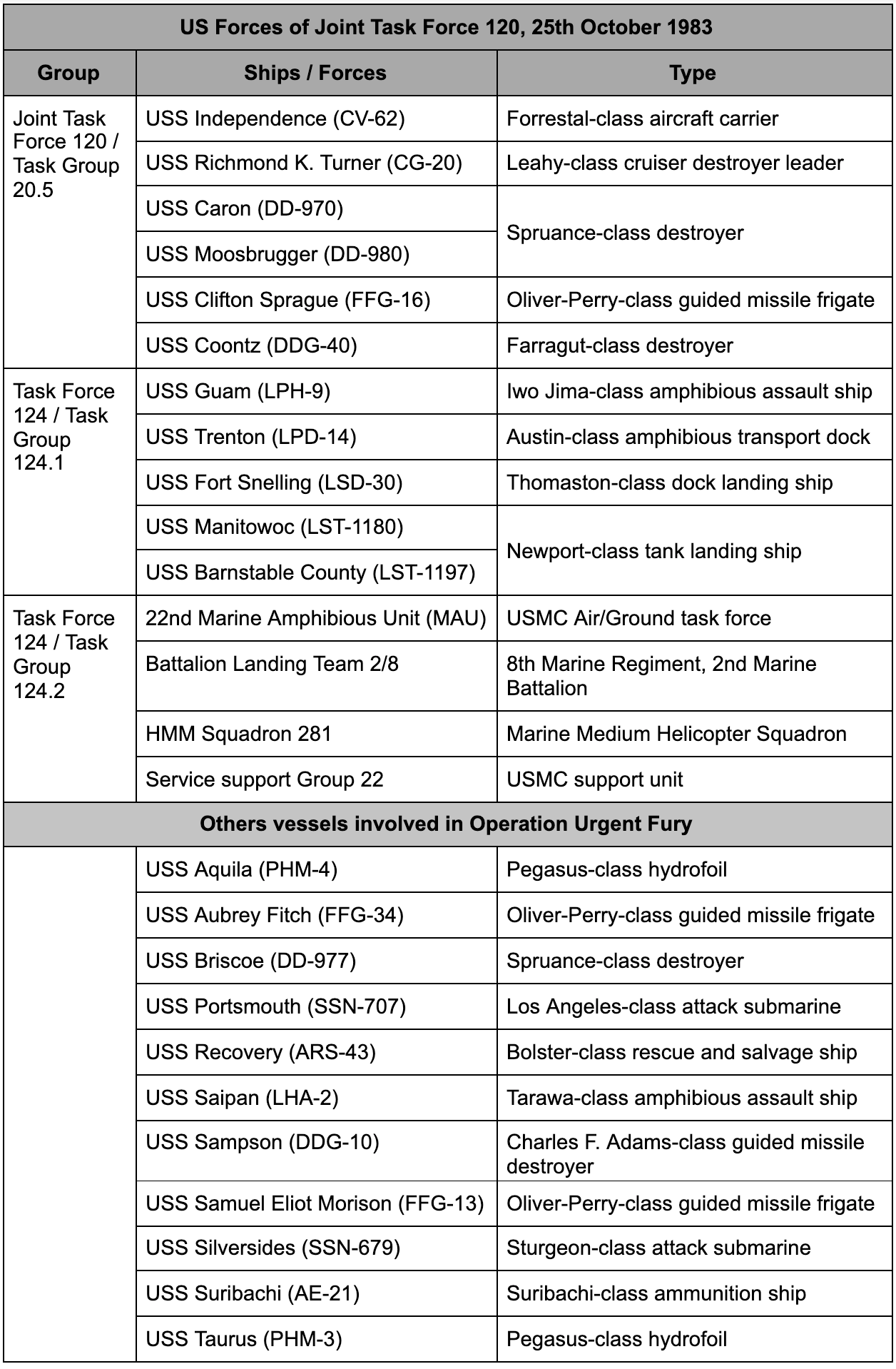

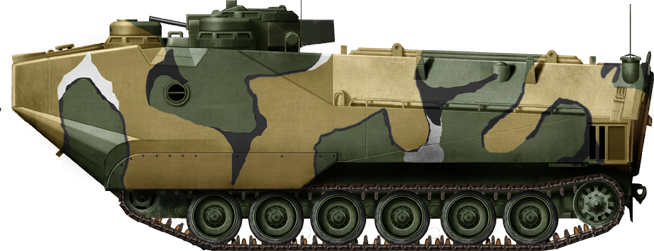

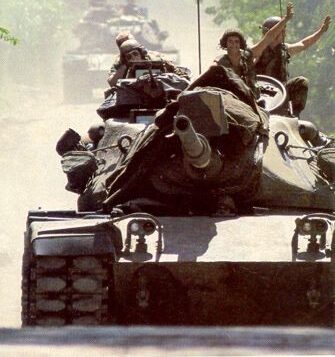

The USMC obliged and, at 1900 hours that day, landed a force from G Company, consisting of 5 M60A1 tanks, 13 amphibious vehicles (LVTP-7s), Jeep fitted with TOW ATGMs, along with 250 men, at Grand Mal Bay. This landing began at 1750 hours and was complete by 1910 hours. It is important to note that the Marines were the only US force to bring tanks with them – the Army brought none. In fact, the Army brought no armored combat vehicles of any kind, and, perhaps for this reason, the Marines found their life substantially easier. By 0400 hours, 26th October, F Company began to arrive as well by helicopter and G Company moved south and east to trap the Grenadians and any Cuban support and also to try and rescue the SEALS at Government House. With their armor advantage, resistance was light, as there were few weapons available to the militia with which they could put up any defiance. It was not until 0712 hours that this Marine force finally reached Government House.

The M60 was a 1950s design for a new main battle tank and is distinguished by a large cast steel turret and hull with a large flat glacis plate. With armor 109 mm and 254 mm thick on the front of the hull and turret, respectively, and side armor 36 – 76 mm thick, the tank was completely impervious to small arms and machine gunfire. Nothing short of a rocket-propelled grenade or dedicated anti-tank weapon, like a recoilless rifle, was going to have any effect.

Armed with an American version of the British L7 105 mm gun known as the M68 in US service, the tank carried probably the finest tank gun ever made at the time and one which remains in service to this day. Coaxial armament was a 7.62 mm M73 machine gun and, on top of the primary turret, was a small cast turret for the commander with a .50 caliber M2 machine gun. Production of the original M60 ceased in 1962, with the adoption of the improved model known as the M60A1. Powered by a Continental AVDS-1790-2A petrol engine delivering 750 hp, the 47.6 tonne M60A1 was capable of 48 km/h (30 mph) on a road.

From 1977, the M60A1 was receiving a new major upgrade in the form of new sights and a deep wading kit, as part of the M60A1(Rise)(Passive) modification. The most noticeable part of the deep wading kit is the exhaust extension which attached to the rear right grille on the engine bay. This wading kit allowed the tank to cross waterways up to 4.6 m (15 feet) deep at a speed of up to 14.5 km/h (9 mph).

Source: Hunnicutt

Source: Hunnicutt

Source: US National Archives

Source: Toronto Public Library

Source: Toronto Public Library

Source: Pintrest

Source: Christian Sungit on Pinterest

Source: Bettmann via Getty

Source: US National Archives.

Source: Christian Sungit on Pinterest

The LVTP-7, or Landing Vehicle Tracked Personnel 7, was often just known as an Amtrack or just ‘Track’. It was the primary means of getting Marines to shore during an assault. Known officially as the Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV), it was exactly that, a tracked fully amphibious armored personnel carrier. Entering service in the early 1970s, the LVTP-7 was a hefty 29 tonne in weight, but could manage up to 72 km/h (45 mph) on a road and up to 13.2 km/h (8.2 mph) in the water courtesy of a Detroit Diesel 8V-53T 400 hp diesel engine.

Protection for the men inside, 3 crew and up to 20 troops, was provided by 45 mm of aluminum, meaning that it too was proof against small arms fire. The armament was modest, with just a single .50 calibre M2 heavy machine gun.

Source: US National Archives.

Source: US National Archives.

Source: Christopher Grey, USMC via USMC

At 1000 hours, the Governor-General, his wife and 22 special operations personnel (all but one of whom had been wounded) were evacuated by helicopter from Government House to the USS Guam. Two hours later, Sir Paul Scoon was returned to Point Salinas at his request until St. George’s could be liberated and he could start to assist in the transition from the anarchy of the invasion to a semblance of law and order. By this time, those Marines of G Company were in a lengthy firefight with the troops defending Fort Frederick. Realizing they were going to be surrounded and annihilated, the PRA commander and men wisely fled, leaving the Marines another victory to their tally for operations on the island.

With the success of the Marines at Fort Frederick and recovery of the Governor, the end was in sight, but there were still a large number of students unaccounted for more than 24 hours into the invasion. They were believed to be held at the campus at Grand Anse. In the advance on Grand Anse Campus, the force encountered fierce resistance from Cubans at Frequente, just one mile north of True Blue Campus. More enemy forces were detected at Grand Anse Campus and the advance halted for a rethink by Gen. Schwarzkopf.

The result of this rethink was a helicopter landing by Rangers using Marine helicopters to drop the men at Grand Anse and a redrawing of the tactical boundaries between the Marines and Rangers to reflect this new area of operations. Troops from the 82nd Airborne were now to be used to take the beach at Grand Anse, supported by a helicopter assault by Rangers carried in CH-46s.

Finally, there had been a realization that the assumption that this tiny island, with its ‘third rate’ force, would just give up and go home was a false one. It was tougher than it looked and, finally, with a ground commander in the form of General Schwarzkopf accepting that inadequate preparations were costly in time and lives, a proper operation was going to happen at Grand Anse. Rangers would come in via CH-46s to seize the campus following an extensive bombardment of PRA positions from A-7 Corsairs, AH-1C helicopters, an AC-130 gunship, and naval gunfire.

At 1600 hours, 26th October, after a suitable pummelling of PRA positions, the Rangers were dropped at the campus at Grand Anse by 6 Marine Corps Sea Knight helicopters and into a 30-minute firefight. Resistance was continuous but relatively light and, although some minor injuries were suffered amongst the Rangers and Marines, no one was killed. Some 224 medical students were then evacuated by CH-53 helicopters and US forces now learned of yet another campus with students to rescue – this time at Lance aux Epines, east of Point Salinas. The only casualty of the entire operation on the American side was a single CH-46 Sea Knight which had been hit by small arms fire. It had to be abandoned when the rotor clipped a tree and the crew evacuated by sea. All told, a properly planned operation with adequate resources had proven a success, with all of the students evacuated and no casualties.

Photographed a few days after the assault, the CH-46 Sea Knight of HMM-261 on the beach at Grand Anse. It had been hit by small arms fire but was lost when the rotors clipped a tree, making it unflyable. Abandoned, the crew escaped offshore in a liferaft unhurt.

Source: Pintrest and airandspacehistorian.com respectively

By this time, the Rangers and Marines were utterly exhausted, after nearly two days of continuing operations and unexpectedly fierce resistance from the Grenadians and Cubans. This exhaustion was compounded by a logistics failure where they had been landed without enough food and water, as soldiers discarded rations for ammunition and misunderstood the need for water in combat on a tropical island. This only got worse when prisoners were taken and had to be fed and watered as well, meaning supplies had to be flown in. It was not much better for the Marines. They might not have had to carry as many supplies as the Army did, but the vehicles needed fuel and, between them and the fuel needed for aircraft, there was a distinct shortage.

This was not helped by the inability to refuel Army helicopters on Naval craft because the nozzles would allegedly not fit and fuel had to be flown in and landed in collapsible bladders. This was not even the acme of inter-service issues and, in one example, when Army helicopters of 160th Aviation Battalion did land on the USS Guam, the Naval Comptroller in Washington ordered the ship not to refuel them due to the costs coming out of the Naval budget. Such a petty and pointless bureaucratic hurdle could have crippled helicopter operations and, perhaps thankfully for the whole venture, General Schwarzkopf broke out the common sense cane and ordered them to be refueled despite the orders to the contrary.

Two more battalions of men from the 82nd Airborne were requested to bolster US forces and provide enough for some break from operations for both Rangers and Marines. These men arrived at 2217 hours at Point Salinas, meaning, by now, more than 5,000 US airborne troops were in Grenada on top of the Marines and SEALs.

Despite having lost the capital, the airfield, and the strongholds at Forts Frederick and Rupert, resistance was still in effect through the night of the 26th and into the 27th. Marines from G Company in St. George’ patrolling in a Jeep that night managed to locate another PRA BTR-60PB. They engaged the vehicle with 66 mm LAWs and knocked it out. This marked the fifth and final BTR-60PB to be knocked out or otherwise abandoned under fire from American forces.

Source: US National Archives.

The Marines had continued to move out from St. George’s, suppressing any sniper activity, as had the Airborne troops in the south as they moved to the east across the tip of the island. They were slowed both by anticipation of strong resistance from Grenadian and Cuban forces, but also by two problems of their own making. The first was damage to Point Salinas airfield slowing down the supply deliveries and the second was the failure of radio communications between the Army and Navy. This latter issue meant that no fire support could be delivered by Naval gunfire, as the Army could not talk to them, so instead had to call Fort Bragg and ask them to convey the fire mission for them.

As resistance was progressively squashed, it was apparent that the barracks at Calivigny was still not in American hands, despite being a priority in both of the original plans. The attack on the barracks was conducted at 1750 hours on the 27th by Rangers landed via UH-160 Black Hawk helicopters and preceded by naval gunfire. Opposing them were just 8-10 men who had actually moved from the barracks to a ridgeline overlooking it.

Source: US National Archives.

The fight which followed lasted until 2100 hours and left one helicopter pilot shot and wounded and three helicopters damaged (two from crashing into each other, and a third which crashed trying to avoid the other two) but the barracks in the hands of the Rangers.

In yet another incident of poor interoperable communications between the Army and Navy, there was a serious blue-on-blue incident just east of Frequente. This had been the scene of fierce fighting on the 25th and sniping was still being experienced by US forces on the 27th in the area of a small sugar mill. An Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Company team called in an airstrike to deal with this sniper, but was unable to coordinate this strike with the 2nd Brigade Fire Support Element on the ground and it was 2nd Brigade Command Post which was nearby. The A-7 Corsairs delivered their fire support but, due to this error, managed to deliver it on the command post rather than on the sniper location. The result was 17 men wounded, 3 of whom seriously. Major combat operations ceased by the end of the 27th, but there was now a very real concern of an insurgency taking place to oust the American invaders.

Indeed, the priority targets of the government, men like General Austin and Bernard Coard, were nowhere to be found and it was necessary to continue a search into the interior of Grenada to locate them and ensure no resistance was being organized by up to ‘500 Cubans’. The 28th of October marked, finally, the purported original goal being accomplished – the final rescue of American students. The campus at Lance aux Epines was reached by men of the 82nd Airborne and 202 US students were located. The 28th, was, however, not the end of combat operations, as concerns over the insurgency meant that a Marine battalion was now to be landed at Tyrrel Bay, Carriacou on 1st November. Scouted beforehand by a SEAL team, this was known as Operation Duke and involved men from G Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines USMC, Task Force 124 from the USS Saipan. F Company was brought into Carriacou Island via helicopter at Hillsborough Bay to seize Lauriston Point airstrip.

The landing was conducted at 0530 hours, supported by ground-attack aircraft in the form of 8 A-10 Thunderbolts. The landings, both amphibious and by helicopter, were, however, unopposed and the complete objective was achieved in just 3 hours, leaving 17 PRA troops and some equipment captured, but none of the rumored Cubans organizing an insurgency.

Source: US National Archives

Source: Peter Leabo.

All combat operations for the original operation were completed at 1500 hours, 2nd November, and US forces were progressively withdrawn as stability was put in the hands of the OECS forces. The last US forces left on 12th December. On 10th November, all military troops who took part in Operation Urgent Fury were made eligible to receive the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal.

Source: US National Archives

Source: US National Archives

This Soviet-made BTR-60PB was recovered intact at Port Salinas airport. It was shipped back to the United States for examination.

Source: US National Archives

Source: US National Archives

Source: Pinterest

The Costs

In terms of combat-related casualties, the US suffered 19 dead, 116 wounded, and 28 non-combat-related injuries. Of the Cubans on the island, 25 were dead, 59 wounded and 638 taken into custody. A number of other nationals of ‘unfriendly’ nations were also detained, including some East Germans, Bulgarians, Soviets, and North Koreans.

For the Grenadian forces, both PRA and any PRM forces, some 45 had been killed and another 358 wounded. Twenty-four civilians also perished in the invasion between stray bullets and the mistaken airstrike on the mental hospital.

There was a political price for the invasion too. The Soviet Union was generally uninterested in the whole affair and happily recognized the established government under Sir Paul Scoon without issue, but it was the Allies that had been more irked. Canada had already arranged a peaceful evacuation of its own citizens from Grenada and was more than a little concerned that what was seen as a reckless endeavor by the Americans putting them at risk.

The British Government, led by Margaret Thatcher, was in an even worse position. Just a year after the successful British operation, supported by Reagan, to retake their own islands from an Argentine invasion, the good will had been destroyed in the eyes of many. Thatcher was described in unflattering terms as being a poodle to Reagan and there were calls in the House of Commons for the British Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe to resign. Of both domestic and strategic importance for the UK was how that somewhat unilateral American action might affect Thatcher’s decision about allowing British soil to be a base for US cruise missiles. It also had put a large number of British citizens at risk of being killed, as well as being the invasion of a member of the British Commonwealth.

In the aftermath of the invasion, CIA translations of captured documents showed no less than five agreements between the Bishop Government and the Soviets and Cuba about providing military aid. Much was made of this for political reasons to post-fact justify the invasion as a ‘we told you so’, but the total of the aid involved was just US$30.5 m and covered relatively minor military supplies, like rifles and uniforms, with the most serious items being anti-aircraft guns.

“There is no getting around the fact that the United States and its Caribbean allies have committed an act of aggression against Grenada. They are in breach of international law and the Charter of the United Nations”

Dennis Healey MP (Deputy Leader of the Labour Party –

the opposition) to Parliament 26th October 1983

In an accounting post-war provided to the US Congress by General George Crist (USMC), the totality of arms captured on Grenda was 158 sub-machine guns, 68 grenade launchers, 1,241 AK47 rifles, 1,339 Mod.52 rifles, 1,935 Mosin Nagant carbines, 506 Enfield rifles, and a few hundred miscellaneous pistols, flare guns, air weapons, and shotguns. Heavy-weapon wise, there were just 5 M-53 quadruple 12.7 mm AA guns, 16 ZU-23-2 AA guns, 3 PKT tank machine guns, 23 PLK heavy machine guns, 20 82 mm mortars, 7 RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenades, and 9 M20-type (Chinese copies) 75 mm recoilless rifles.

Source: Pinterest

Source: Pinterest

That was smoke and mirrors to deflect from a poorly planned and poorly executed operation. Notwithstanding some rapid and innovative command decisions on the ground, the whole thing was a mess. Reagan was also to pay a price, as no concession had been made to allow reporters to see what was going on and the first members of the press did not get to arrive until the 28th. This gap did, however, manage to serve a couple of purposes – firstly, it allowed a false narrative of ‘battalions’ of Cuban regular forces to be propagated to allay in some way the problems of command and control. Secondly, it ensured that only ‘the good bits’ would be seen and that, should things go horribly wrong with numerous civilian casualties, it would not reach the public.

Source: Pinterest

The military operation on Grenada was a success in the sense that it recovered the students and restored a government on the island. It was also a success in that it highlighted serious shortcoming in US military preparedness and joint operations. Reagan got his win in his tropical adventure on the island, but for sure he did not assert the prowess of US military might he may have wished to do. Notwithstanding the efforts of Clint Eastward to portray this as some fight against heavily armed Cuban regular troops, the real story was a mess compounded by shambles and wrapped in disorganization.

In the long run, the arguments over the justification for the invasion faded and the people of Grenada were happy with the outcome in terms of the restoration of law and order and a return to the per-1979 coup state where new democratic elections could be held.

Conclusion

Review

The invasion was put together at short notice, despite the fact that plans should already have been in place. Likewise, the grossly ill-prepared force in terms of things like maps should never have happened. The fact that more American personnel were not killed in the operation is more due to luck than anything else and the hubris of assuming the ‘third rate’ enemy would somehow melt away when the US military showed up can be highlighted as arrogance which cost lives. The real winners of Grenada were the American troops who proved themselves rugged, capable, and flexible when they needed to be, both as regular forces, Marines, and special forces. The US military itself would also benefit in general from a review of the problems and on 22nd May 1984, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the Army and Air Force to work on 31 identified warfighting deficiencies. Specific in those were air surveillance, the identification of friendly forces to reduce the chance of friendly fire, and tactical missile systems amongst others. The wider Goldwater Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 was also created in part to learn from the failures identified in the invasion.

In taking the island from this “third rate, lightly armed and poorly trained adversary”, the US had had to bring to bear some 8,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines and had taken over a week in the midst of an uncoordinated attack with inconsistent and often unhelpful air support. Resistance, and in particular the air defense from what was just manually laid ground batteries, had proven particularly effective. The loss of several aircraft damaged and destroyed pay testament to how effective a well-situated anti-aircraft gun could be and how vulnerable an assault overly reliant on delivery of forces by helicopter could be. It was only by luck that none of those C-130 delivering Rangers had been hit or a full helicopter of special forces did not go down. Indeed, the only force to have little trouble was the one that bothered to bring armor in the form of LVTP-7s and tanks. With little they could do to counter these vehicles, the opposition often simply melted away. The lesson should have been that bringing armor on your operation and not relying on light vehicles or helicopters was the way forward, especially for work in an urban area, yet, 10 years later in Mogadishu, Somalia, the US had to relearn that particular lesson again.

The bigger US lesson was a political one. The invasion served as a perfect operation if a distraction was needed from the disaster in Lebanon. It also laid the groundwork for a new and more assertive US foreign policy in the form of the ‘Reagan Doctrine’ in February 1985 which directly impacted other US interventions in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and the invasion of Panama.

Souvenir

The BTR-60 which had been captured intact on Grenada was recovered to the United States for a technical evaluation. At this time, the BTR-60PB was still a potential front-line adversary vehicle used by the Soviet Union, so capturing a complete one was a rare opportunity to examine it technically. With this intelligence objective achieved, the vehicle was sent to Fort Barret at Quantico Marine Corps Base in Virginia as a training aide.

Long-Term

The runway at the heart of the American concerns was finished and eventually opened and known as Point Salinas International Airport and also Grenada International Airport. In 2009, the airport was renamed Maurice Bishop International. Bernard Coard survived the invasion and, along with 16 others, was sentenced to death for their part in the coup and murders – sentences later commuted to life in prison. They were released from custody in 2009.

Sources

Airspace Historian: Operation Urgent Fury. July 2018. https://airspacehistorian.wordpress.com/2018/07/#_edn150

Brands, H. (1987). Decisions on American Armed Intervention: Lebanon, Dominican Republic, and Grenada. Political Science Quarterly, Vol.102, No.4

CIA: Interagency Intelligence Assessment of Cuban and Soviet involvement in Grenada. 30th October 1983. Central Intelligence Agency.

CIA: Grenada’s Security Forces. CIA.

Cole, R. (1997). Operation Urgent Fury – Grenada. Joint History Office, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Washington DC, USA

DDI: Talking points on Grenada. 19th October 1983. DDI.

Doty, J. (1994). Urgent Fury – A look back – A look forward. US Naval War College, USA

Grenada Airport Authority http://www.mbiagrenada.com

Grenada Revolution Online. http://https://www.thegrenadarevolutiononline.com/

Hansar. ‘Grenada (Invasion). Mr. Denis Healy. HC Deb. 26 October 1983 vol 47 cc291-235.

Harper, G. (1990). Logistics in Grenada: Supporting no-plan wars. US Army War College, USA

Haulman, D. 2012). Crisis in Grenada: Operation Urgent Fury. https://media.defense.gov/2012/Aug/23/2001330105/-1/-1/0/urgentfury.pdf

Hunnicut, R. (1992). Patton: A History of the American Main Battle Tank Vol.1. Presidio Press, USA

Johnson, J. General John W. Vessey Jr. 1922-2016: Minnesota’s top soldier. Military Historical Society of Minnesota. https://www.mnmilitarymuseum.org/files/2614/7509/1505/Gen_John_W._Vessey_Jr..pdf

J-3. (1985). Joint Overview of Operation Urgent Fury.

Kandiah, M., & Onslow, S. (2020). Britain and the Grenada Crisis, 1983. FCDO Historians.

Labadie, S. (1993). Jointness for the sake of jointness in Operation Urgent Fury. Naval War College, USA

Loon, M., & Baumgardner, N. (2019). The US Historical AFV Register Ver. 4.3. http://the.shadock.free.fr/The_USA_Historical_AFV_Register.pdf

Memorandum from Assistant National Intelligence Officer for Latin America to Director of Central Intelligence Deputy Director. Status of efforts to exploit Grenada documents. 1st June 1984.

Moore, J. (1984). Grenada and the International Double Standard. The American Journal of International Law. Vol. 78, No. 1.

National Foreign Assessment Center. Grenada: Two years after the coup. May 1981. NFAC

Office of the Historian. Foreign Relations of the United States 1969-1976 Vol. XXVIII, southern Africa. 132. Report Prepared by the Working Group on Angola No.75. 22nd October 1975

Plane and Pilot Magazine. Boeing 747 1969-Present. https://www.planeandpilotmag.com/article/boeing-747/

People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada. (1981). Is freedom we making: the new democracy in Grenada. Coles Printery Ltd., Barbados. http://cls-uk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Is-freedom-we-making.compressed.pdf

Rivard, D. (1985). An analysis of Operation Urgent Fury. Air Command and Staff College, USA

SIPRI Trade Register Transfers of major weapons. 1950 to 1990 recipient: Grenada.

Bailey, C. (1992). PSYOP-unique equipment: Special weapons of communication. Special Warfare Magazine. PB 80-92-2. Vol. 5 No. 2. October 1992

Spector, R. (1987). US Marines in Grenada 1983. History and Museums Division, HQ USMC, USA

Trinidad and Tobago Newsday. (11th October 2020). Grenada Revolution: ‘We come for Maurice’. https://newsday.co.tt/2020/10/11/grenada-revolution-we-come-for-maurice/

Ward, S. (2012). Urgent Fury: The operational leadership of Vice Admiral Joseph P. Metcalf III. Naval War College, USA

White House. (1983). National Security Directive 110, 21st October 1983

White House. (1983). National Security Directive 110a, 21rd October 1983

8 replies on “1983 US Invasion of Grenada”

The Land Rover in one of the early pictures is a series IIA. You slao mention a ZSU-23-2 anti-aircraft gun. It is in fact the ZU-23-2.

sorry -it should read “also” – big fingers!

The M-60 series tanks all had diesel engines and never had gasoline engines as the M-48 series originally had. In 1983 the M-60, M-60A1 (shown in these photos), and the M-60A3 were all in use by the US Army. Some units still had M-48A5 tanks, and M-1 tanks were entering service in increasing numbers. My Texas Guard unit was equipped with M-60 tanks until we were re-equipped and retrained for M-60A3’s in 1988. My civilian job at the time was making the microprocessor for the M-1 tank’s fire control computer at a wafer fab facility in Houston. During 1982-85 both woodland camo BDU’s and green fatigues were worn in my unit. We didn’t get Kevlar helmets until late 1985.

It says at a couple of places USS Gaum?Shouldn’t it be USS Guam?

There were a number of other similar mistakes. Proof reading in general seems to be a lost art of late.

Very nice choice in topic, I always was fascinated by the Granada Invasion. I love the Patton in ERDL. Thanks!

Thanks for sharing this! All the best!

Wow that Marine track has an M60 fitted instead of the M85 turret? Some great pics I’ve never seen before, that aerial shot of the M60 and MUTTs is so great.