Vehicles

Prisoners of Geography

Chile and its military are defined by the country’s peculiar geography. From north to south, Chile extends 4,270 km (2,653 miles), and yet it only averages 177 km (110 miles) east to west. To its west is the immensity of the Pacific Ocean, whilst, on its east, lays the near impassable Andes mountain range. Chile’s northern neighbors are Peru and Bolivia, and its border with Argentina to the east, at 5,150 km (3,200 miles), is the world’s third-longest. Chile has territorial disputes with all its neighbors.

Based on the different climates, Chile can be divided into several parts. The far north (Norte Grande), which extends from the Peruvian border to about 27° south latitude, is extremely arid, containing the Atacama Desert, one of the world’s driest. The near north (Norte Chico) extends from the Copiapó River to about 32° south latitude, or just north of the capital Santiago and is a semiarid region. Central Chile (Chile Central), home to a majority of the population, includes the three largest metropolitan areas (Santiago, Valparaíso, and Concepción) and has a Mediterranean climate. The South (Zona Sur) is one of the wettest areas on Earth. Lastly, the far south (Chile Austral), which extends from between 42° south latitude to Cape Horn, the Andes and the South Pacific, is in parts a very cold area and mainly uninhabited.

Brief Introduction to Chile

Chile, like many of its neighbors, gained independence from Spain in 1818. The new Republic would soon be embroiled in conflict, fighting Spain in Peru and a civil war between different factions for the control of the country.

Between 1836 and 1839, Chile defeated the Bolivian-Peruvian Confederation, resulting in the dissolution of the vanquished. Between 1865 and 1866, Chile, alongside Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia fought an inconclusive mainly naval war with Spain, in which Valparaiso, Chile’s main export port, was destroyed. In 1879, Chile again fought its former Bolivian and Peruvian allies in the War of the Pacific. The peace accord ending the war signed in 1884 saw Peru lose territory to Chile, and, crucially, lose Bolivia its access to the sea.

In 1891, a constitutional and budgetary crisis led to a civil war, with the army and navy taking different sides. The revolutionary faction, with the support of the navy, was victorious and formed a parliamentary republic.

At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, Chile sought close relationships with its larger neighbors, Argentina and Brazil. Chile chose to remain neutral during World War One.

In September 1924, the armed forces mounted a coup and gave way to a presidential republic. The Economic Crisis of 1929 affected Chile negatively and led to public discontent which manifested itself in several revolutionary and coup attempts throughout the decade.

Chile and WWII

Between December 1938 and November 1952, Chile was dominated by the Partido Radical (Eng. Radical Party). Formed to represent the nascent and expanding middle classes, with a liberal platform and an emphasis on state intervention, the early period was heavily influenced by pre-WWI Imperial Germany. The Partido Radical would not rule alone, but at the head of coalitions also including Socialists, Communists, other democrats, and even Christian Democrats (the traditional opponents of left-wing parties).

One major hurdle the first Radical government, with Pedro Aguirre Cerda as president, would face was the denunciation of Popular Front governments by the Soviet Union after the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, damaging the delicate coalition. However, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 normalized relations between the government and the Communists.

With Cerda’s death from tuberculosis in November 1941, a new Radical-led popular front government under Juan Antonio Ríos was pressured by the USA to break relations with the Axis powers in 1943, despite their intention to remain neutral. Chile went on to declare war on Japan in 1945. At this time, Chile exported large amounts of copper and potassium nitrate, necessary for the production of ammunition, to the USA. In exchange, the USA gave Chile armored vehicles.

The state of Chile’s armored forces in 1945

In spite of being neutral for almost the entirety of WWII, Chile benefited from its close relationship with the USA in the expansion of its armored forces.

Chile had first obtained armored vehicles in 1936, with the purchase of five Vickers-Carden-Loyd Mk.VIs destined for the Escuela de Aplicación de Infantería (Eng. Infantry Training School). By 1945, these five vehicles had been moved to the newly formed Escuela de Unidades Motorizadas (Eng. Motorized Units School) and later to the Carabineros (the Chilean police), before being retired during the 1950s.

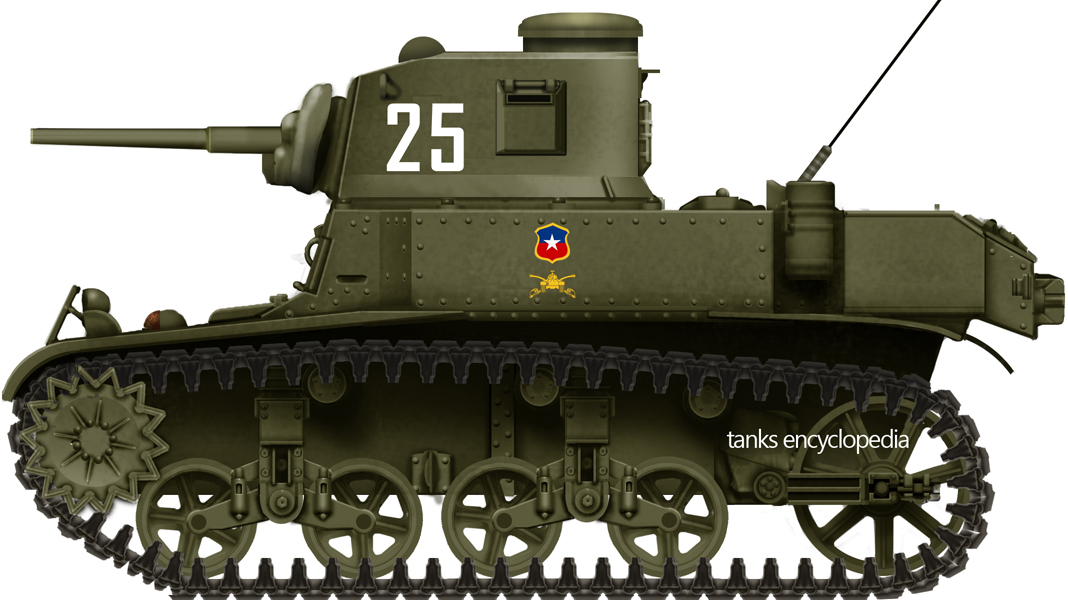

In 1943, the USA sent a first shipment consisting of between 12 and 17 M3A1 Stuart tanks, 12 M3A1 half-tracks, and 15 M3 Scout Cars. Additional (possibly 18) M3A1s were sent between 1944 and 1945, causing a great impression on military and civilian authorities. As the Second World War ended, Chile received more M3A1 Stuarts, increasing the total number to close to 50.

The early Cold War

President Ríos died of cancer in June 1946, prompting new elections, again won by the Radical coalition, by then under Gabriel González Videla, and with prominent Communists in positions of power. Within a year, the coalition became fractured and, in the summer of 1947, the Communists instigated and encouraged aggressive strikes protesting against government policies. With the USA piling on the pressure, the Chilean parliament almost unanimously passed the Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia (Eng. Permanent Defense of Democracy Law), banning the Communist Party and forcing prominent Communists, including Senator Pablo Neruda (Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971), into exile.

The Partido Radical’s rule came to an end in 1952 with the election of the populist president General Carlos Ibañez del Campo and his promise to improve the country’s economic fortunes. Although he had left-wing policies in his early years in office, US meddling ensured Ibáñez del Campo’s adoption of more liberal economic policies.

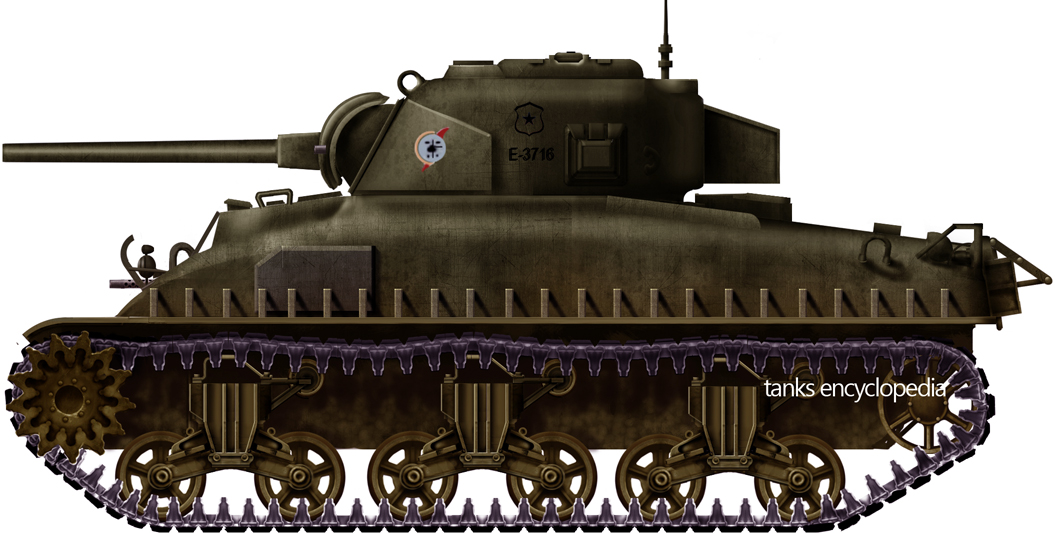

This period saw the incorporation of further US armor: 5 additional M3A1 half-tracks in 1950, at least 21 M24 Chaffees in 1952, 5 M8 Greyhounds in 1953, and 17 M4A1E9 Shermans, and 3 M32 ARVs in 1953. Whilst the Shermans would revolutionize Chile’s armed forces, the Chaffees and the Greyhounds were not very highly regarded. Specifically, the Chaffee’s twin Cadillac engine was not appreciated. In the case of the Greyhound, Chile’s military authorities preferred tracked vehicles over wheeled vehicles, as they performed better across the deserts in the north of the country and the tundra in the south.

The Tercios and the Rise of Allende

The period between the 1958 and 1970 presidential elections in Chile is known as Tercios, where three distinct political ideologies competed for the presidency: Liberalism, Christian Democracy, and Socialism.

The 1958 presidential election was narrowly won by the Conservative-Liberal coalition led by Jorge Alessandri. Seeing how close the election result was and the rising popularity of the Socialists, led by Salvador Allende, the USA took a close interest in developments in Chile.

The run-up to the 1964 election was characterized by mass foreign interference. Fearing Allende becoming President, the Conservative-Liberal coalition did not put up a candidate, giving the Christian Democrat candidate Eduardo Frei Montalva a clear path to the presidency. The American Central Intelligence agency (CIA) covertly spent US$3m campaigning against Allende while the USSR spent a large amount of money supporting him. Frei Montalva won the election comfortably.

Frei Montalva faced many difficulties, including numerous strikes and even an attempted coup in October 1969. That coup attempt came from the Tacna artillery regiment, led by General Roberto Viaux, demanding better pay and the purchase of new military materiel.

In 1964, the USA, under the Military Aid Pact, sent 10 or 17 M41A1 Walker Bulldogs to Chile, followed by a second batch of 40 or 43 M41A3s in 1970, alongside 3 M578 ARVs, and 60 M113A1 APCs.

In other branches, the Infantería de Marina (Eng. Marine Infantry or Marines) incorporated in 1965 four LVTP-4s of US origin, but which had been in the service of the state-owned Empresa Nacional del Petróleo (Enap). At some other point, they also incorporated a number of 4×4 MOWAG Grenadiers.

The agreement between the Christian Democrats and the Liberal-Conservative coalition fractured before the 1970 election, with each faction presenting a candidate. Allende was the winner of the election with close to 37% of the vote. Having not won an outright majority, Allende needed the support of the Parliament to become President. The USA, with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger taking a lead role, put two plans forward to stop Allende. Track I was to prevent the Chilean Parliament from confirming Allende through a quasi-democratic process, whilst Track II was the military coup option. However, for the latter plan to succeed, first, the pro-Constitutionalist Chief Army, Commander René Schneider, would have to be removed. An attempted kidnap planned by Viaux resulting in Schneider’s death galvanized parliament and the Chilean population to back Allende and the constitution.

The Fall of Allende

Under Allende, Chile experienced a democratic Socialist revolution, which saw widespread nationalization, including the prosperous and powerful copper industry, without compensation and the expropriation of agricultural land, again, without compensation.

Whilst the first year of Allende’s presidency was very popular and his Popular Front won the 1971 municipal elections with almost 50% of support, the detonating economic situation caused in part by international sanctions and the suspicions of Conservative elements of society put Allende in a perilous situation. The CIA was still interfering in Chile and supported and financed a truck drivers’ strike in October 1972. At the same time, more radical elements within his coalition wanted an outright revolution instead of Allende’s democratic reforms.

The opposition began to rely on the military to put an end to Allende. In the early morning of June 29th, 1973, the Regimiento Blindado N.º 2 (Eng. Armored Regiment No. 2), under the command of Lt. Col. Roberto Souper, took to the streets of Santiago, heading for the Palacio de la Moneda (the Presidential palace) and the Ministry of Defense. The column included 80 soldiers and 16 M41 Walker Bulldogs, which used their machine guns to fire upon the Presidential Palace. In the end, troops loyal to the government were able to force Souper and his tanks to surrender.

The coup, which has since been known as the ‘tanquetazo’ due to the large number of tanks used (one of the words in Spanish for tank is ‘tanque’), failed, but the situation was, nevertheless, still one of crisis. To calm the situation and reaffirm his position, Allende had the intention of calling for a plebiscite on his position as President of the Republic.

However, this was not to be. From August, a newly planned coup was in the works, which, unlike the tanquetazo, could count on all the branches of the armed forces. On September 7th, 1973, Augusto Pinochet, the new Commander in Chief of the Army, had been convinced to join the coup by Vice Admiral José Toribo Merino and General Gustavo Leigh. Pinochet had previously been considered a loyal and apolitical officer. In the early morning of September 11th, 1973, the Chilean fleet took Valparaíso. By 10 o’clock in the morning, tanks were yet again on the streets of Santiago and, just before noon, Hawker Hunters of the Chilean Air Force bombed the Palacio de la Moneda. Allende committed suicide and, by the end of the day, a military junta had taken control of the country. Whilst the exact role of the USA and Nixon administration in the September coup is unclear, what is clear is the CIA’s covert spending in Chile, US$8 million in the three years between 1970 and September 1973, with over US$3 million in 1972 alone.

Pinochet

Within a year and a half, Pinochet centralized all power around his figure and unleashed massive repression against those who had supported Allende. In all, conservative estimates state that, during his regime, 3,000 people were murdered, alongside at least 35,000 people tortured, and 300,000 people detained.

Pinochet introduced neoliberal economic policies influenced by Milton Friedman and carried out by the Chicago Boys. In the early years of Pinochet’s rule over Chile, there were good relations with other military despots on the continent, especially with the Brazilian military junta. In 1974, a batch of 12 EE-9 Cascavel Mk IIs arrived in Santiago from Brazil, followed by an additional 48 between 1975 and 1977. Alongside the last batch of EE-9 Cascavel Mk IIs were 17 EE-11 Urutu Mk IIs, followed by an additional 20 and 4 ambulance models in the following years. In December 1978, 23 of the improved EE-9 Cascavel Mk IIIs were received by Chile.*

In 1975, there was a rapprochement with Bolivia, and Pinochet and his fellow anti-leftist military dictator, Hugo Banzer, attempted to solve the issues surrounding the loss of Bolivia’s access to the sea as a result of the 1879-1884 Guerra del Pacífico between the two countries. That same year, the Infantería de Marina bolstered its forces with the arrival of 26 LVTP-5s.

*It is important to note that there is some disagreement between Chilean sources and Brazilian and Engesa sources. The EE-9 Cascavel Mk IIIs may have just been upgraded Mk IIs with the new 90 mm EC-90 main gun but the old turrets. Similarly, there may have been 6 ambulances.

Tensions and Isolation

Following a number of diplomatic embarrassments and the election of Jimmy Carter in the 1978 US Presidential Election, Chile became increasingly isolated.

Earlier, in 1975, tensions with Peru over granting Bolivia a stretch of land which would give them access to the sea almost led to a full-blown war. Peru sent its T-54s and T-55s of the 18.ª División Blindada (Eng. 18th Armored Division) to its border with Chile. A coup in Peru averted the war, but relations between the two countries would not improve.

Due to the strained relationship with Peru, Chile redistributed old materiel, including Chaffees that were previously found in tank graveyards, to frontline and training units. Still, unhappy with the dual Cadillac engines, the tanks were re-equipped with a Maco-Detroit diesel engine.

In May 1977, the UK arbitrated a long-standing border dispute between Argentina and Chile and gave Chile sovereignty over the Picton, Nueva, and Lennox islands in the Beagle Channel. Less than a year later, in January 1978, Argentina rejected the arbitration and claimed sovereignty over the islands. The year 1978 was a tense year and both countries undertook a military build-up with the potential to boil over into war. In December 1978, Argentina was ready to launch Operación Soberanía, which would capture the Picton, Nueva, and Lennox islands alongside a number of other islands it claimed and mount two attacks on Chile. However, an eleventh-hour Papal mediation ended the conflict just as Argentinian troops were ready to go into action.

With those two near misses, Chile understood that it was being left behind by its neighbors, and that its most advanced tanks, the M41 Walker Bulldogs, could not face the Peruvian T-54/55s, or the Argentinean Sherman Repotenciados, let alone the TAMs about to enter Argentinian service.

Chile searched the market for a new tank, considering the British Centurion, the French AMX-13, and the Austrian SK-105. However, these were refused and Austria even went on to sell the proposed Chilean batch to Argentina and Bolivia. In 1980, an agreement was reached to buy 50 AMX-30s from France, with 20, plus a recovery vehicle on the same chassis, arriving the following year. Due to political pressure, France canceled the delivery of the remaining 30.

At the same time, Chile had negotiated with Israel the delivery of between 120 and 150 M-51s to act as a stopgap solution until a better one was found. A period of close military relationships with Israel began and Israeli instructors were sent to train the Chileans in the use of these improved Shermans. Later, throughout the 1980s, Israel upgraded Chile’s M24 Chaffees with a 60 mm Hyper Velocity Medium Support L.70 gun. This vehicle is also referred to as the M-24 ‘Super Chaffee’ in some sources. That same gun was used with a batch of as many as 65 M-50s received from Israel in the mid-’80s, resulting in the M-50 with 60 mm HVMS Gun. There were even plans to upgrade the M41 Walker Bulldog with this 60 mm cannon, but the plan was not deemed worthy enough. Lastly, Israel either sent or helped develop an armored recovery vehicle with a light crane based on an M3 half-track chassis.

The only other vehicle Chile obtained in the 1980’s was the Swiss MOWAG Piranha I (Piraña in Spanish). In 1980, Industrias Cardoen and Fábricas y Maestranza del Ejército (FAMAE) was awarded the license to manufacture the vehicle, and between 1982 and 1988, 100 vehicles were produced, including mortar-carrying variants, ambulances, anti-aircraft and command vehicles, alongside the usual APC version.

Decline and fall of Pinochet

In 1981, Chile’s economic boom came to a halt before receding. Due to the worldwide economic crisis, Chile’s copper exports plummeted. As a result, Chile’s currency, the Peso, was devalued and inflation increased to 20%.

In December 1986, members of the Marxist-Leninist Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez (FPMR) guerrilla group failed in an attempt to assassinate Pinochet. Pinochet and the secret service immediately launched Operación Albania, resulting in the execution of 12 FPMR members.

1987 was a key year in the democratization of the country. Two laws allowed the creation of political parties and the opening of electoral registries, leading the way to democratic elections. Furthermore, Pope John Paul II visited the country and met Pinochet, allegedly recommending his opening up of the democratic process and his resignation.

In 1988, there was a plebiscite on Pinochet’s position, with most legally accepted political parties, including Conservatives, Christian Democrats, and Socialists, campaigning together for the ‘no’ against Pinochet. The campaign won the plebiscite with 54.68% of the vote, and despite initial reservations, Pinochet accepted the result. In line with the 1980 Constitution, this gave way to presidential and parliamentary elections for December 1989. Patricio Aylwin won the presidential election and set in motion the process towards democracy.

In 1988, the Infantería de Marina would receive the first of its Bandvagn 206 of Swedish origin, with more arriving in the following decade.

Available Chilean illustrations:

Bibliography

Juan Miguel Fuente Alba Poblete, Familia Acorazada del Ejército de Chile. Historia de los Vehículos Blindados del Ejército (1936-2009) (Santiago de Chile: Ejército de Chile, 2009)

Nicolás García, Infodefensa.com, Chile, de compras desde la década de los 80 (16 May 2018) [accessed 12/01/2021] https://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2018/07/18/noticia-chile-expande-capacidades-blindadas-fuerzas-armadas.html

Nicolás García, Infodefensa.com, Chile expande las capacidades de sus fuerzas armadas (18 June 2018) [accessed 12/01/2021] https://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2018/07/18/noticia-chile-expande-capacidades-blindadas-fuerzas-armadas.html

Pedro Hormazábal Espinosa, “Evolución de las Unidades Militares de Chile 1944-1982”, Perspectiva de Historia Militar, (July 2019)