United States of America (11 July 1991)

United States of America (11 July 1991)

Official figures from the US military for their losses of personnel during the 1990-1991 Gulf War are well recorded, with a total of 298 men and women killed and 467 wounded across the services. Losses of equipment, however, are less clear. Wikipedia, for example, lists the loss or disabling of 31 M1 tanks, 28 Bradley IFVs, and a single M113 for US forces.

According to the Government Accounting Office (G.A.O.), however, of the 3,113 M1 Abrams and 2,200 Bradleys to the theatre (with 1,089 and 470 respectively held in a theatre reserve), 9 M1s were destroyed with 14 damaged, 7 of the 9 by friendly fire (78 %) and the other 2 (22 %) deliberately to prevent capture after being disabled. According to the same report, it is reported that, for the Bradley, 20 of the 28 (71 %) lost were due to friendly fire but also that the Army’s Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff reported only 20 Bradleys as destroyed and 12 damaged with friendly fire accounting for 85% and 25% of those respectively.

In a single report, different figures for losses and damage are confusing enough and may be related to the period of time in which both groups are defining the terms of their analysis. This serves to illustrate a key problem with counting losses even by the winning side, even with few numbers in a relatively well-defined space and time, but if that is not complex enough as ‘counting’. Consider the single largest loss of M1s which took place after the shooting war was over but was still in the theater. The incident in question was a major fire at Doha, Kuwait, a fire that destroyed over 100 American military vehicles, including 4 M1 Abrams, and is likely the worst one-day loss of vehicles suffered by the US Army since WW2. It is worth noting that the war itself was over by the end of February 1991, so it is no surprise that events happening in July do not count in loss statistics for combat but this has also served to almost conceal this disaster in the aftermath of a successful war.

Doha Base

Camp Doha was a large sprawling military compound located at Ad Dawah, a small projection of land jutting out into Kuwait Bay about 15 km west of Kuwait City. In the immediate aftermath of the liberation of Kuwait from the occupying Iraqi forces, this base was a hub for the US military buzzing with daily activity. Roughly rectangular in shape, lying along the north/south axis, the base was bounded by the Doha Road to the west which ran north to the docks and another road running to the east and going up the peninsula making the northern half a little wider than the southern half of the base.

Divided into two sections, with the southern section consisting of a series of east/west orientated rectangular warehouses with a triangular motor pool in the center. On the very south end was a small UN compound. At the northern edge of the southern compound was a sandy gap, around 200 m wide, separating it from the northern compound, which had a series of barracks buildings in the north (for American and around 250 British troops), a northern motor pool and two large rectangular motor pools on the southern edge. It was in one of these motor pools, on 11th July 1991, that one of the worst one-day material losses in peacetime happened for the US military.

The Fire

It was this motor pool area which was being used as a wash-point for vehicles when a fire began. The vehicles concerned belonged to 2nd Squadron, US 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR), the only part of 11th Cavalry still in the base, as the other two squadrons had been deployed to the field on 11th July to serve as a deterrence against Iraqi aggression. The 3,600 or so personnel of 11th ACR had only been in theater for around a month, having deployed from Germany and having taken no part in the war. The remaining squadron was now left behind to guard the base and maintain the vehicles, etcetera. It was with the vehicles left behind that the accident happened, with the unit’s vehicles packed tightly into rows in the motor pool. A row of M992 Ammunition carriers was parked in a neat row behind a line of M109 Self-Propelled guns and, a short distance north in the motor pool was a line of M2 Bradleys.

The fire began in the heater of one of the M992 Ammunition Carriers at around 10:20 hours that day. The vehicle was laden with 155 mm artillery shells and, as such, the fire was a major concern. Despite the valiant efforts of the men to fight the fire, it grew worse and with the vehicle and those next to it laden with shells, the decision was quite correctly made to abandon the fire and evacuate for safety. This was still underway at 11:00 hours when the first of several explosions took place.

The Explosions

The first explosion took place in the original M992 in which the fire had started and not only wrecked that vehicle but also scattered artillery submunitions (bomblets) over numerous vehicles nearby. Each M992 was capable of holding up to 95 rounds (92 x 155 mm shells of various types such as High Explosive, and 3 M712 155 mm Copperhead rounds). Just like the first M992, the vehicles surrounding it were all laden with ammunition in anticipation of potential combat with Iraqi forces. As further vehicles caught fire and exploded, more vehicles were destroyed and numerous submunitions were scattered around, many of which did not go off or were damaged by the blast and fire. At noon that day, an hour after the first explosion, the 22nd Support Command reported that the entire motor pool had been engulfed in fire, with up to 40 vehicles affected. More concerningly, and something which would cause more problems later on, they also reported that a number of depleted uranium rounds were involved.

A response, 2 and a half hours later at 14:30 hours, advised troops to wear protective masks and to stay upwind of the scene which was to be considered a chemical hazard. However, most troops had their masks stored elsewhere and no masked troops can be found in the photos of the incident.

The explosions and fire continued for several hours as a chain reaction through the vehicles, rattling windows as far away as Kuwait City as the fire spread from one vehicle to another. Various conexs, small metal sheds used to store spare ammunition, also became engulfed along with the rubber, plastics, and fuel in the vehicles. The fire was simply too big and too dangerous to fight, it had to be left to burn itself out.

The Aftermath

After several hours, around 16:00 hours, it was possible for some kind of assessment to be made of the damage to what was a combat-ready unit in a high-risk zone post-war. Numerous troops had been injured in the dash to safety, as troops scattered from the northern compound, although there were no fatalities. Some 50 US and 6 British troops reported injuries ranging from fractures to cuts, bruises, and sprains, as many were hurt climbing the perimeter fence to get away. Dozens of buildings were seriously damaged and the photos of the vehicles caught up in the fire show the scale of the damage.

A burnt-out M1A1 Abrams with turret turned 90 degrees next to an M60 AVLB with bridge raised (left). The foreground is littered with burned debris and exploded, unexploded, and damaged ordnance of various kinds. Source: gulflink.health/mil

Aerial shots of the damage after the fire. Source: Paul Margin Facebook: Doha Dash July 11th 1991

Losses

Some 102 vehicles were lost during the accident, including 3 M1A1 Abrams, an unknown number of M992 Ammunition Carriers, and other vehicles from HMMWVs to Bridgelayers. It was, however, not the vehicle losses which were the most serious fallout from this accident but the cleanup. The M1A1s which were lost had, like the M992s, been loaded with ammunition ready for deployment. Unlike the M992’s, however, these rounds were not mostly explosive-filled but were in fact primarily Armor Piercing Fin Stabilised Discarding Sabot (APFSDS)-type rounds made with Depleted Uranium. Burned and scattered all over the site, there was a total of US$15 million worth of ammunition destroyed, including 660 of those APFSDS rounds – specifically the M829A1 120 mm round.

The 20.9 kg 120 mm M829A1 APFSDS was colloquially known as the ‘Silver Bullet’ i.e. the ‘cure’ for Soviet-supplied tanks in the Iraqi Army. Each shell was filled with 7.9 kg of propellant firing the 4.6 kg 38 mm diameter 684 mm long ‘dart’ at around 1,575 m/s.

Aftermath at Doha. Fire-damaged M829A1 DU APFSDS rounds recovered from the site, mostly from the conexes. Most of the rounds in the tanks remained burnt within the ammunition stowage area in the turret ammunition rack and were not ejected. Source: gulflink.health/mil

The three M1A1s which were lost had been in the wash-down area during the fire and were completely gutted by the fire. A fourth vehicle was damaged but not burnt out. Each of the tanks was loaded with around 37 M829A1 DU APFSDS rounds (111 total). More DU rounds were stored in the MILVAN trailers and conexes and all of the ammunition in the 3 burnt-out Abrams was destroyed.

“All four of the M1A1s were damaged/destroyed as a result of fires external to the vehicle. There were no penetrations anywhere of the exterior armor.* Three of the four M1A1s had their fuel and ammunition destroyed. In these three cases, there was an explosion in the ammunition compartment. The ammunition doors and blowout panels functioned properly, keeping the explosion from entering the crew compartment. The fourth M1A1 was damaged on the right suspension only, and except for the gunner’s computer and transmission warning lights, was completely operational. The damage to the suspension system, however, was extensive”

Para 2: Memo to Commander 22nd Support Command, 5th August 1991

* The part about no penetrations being important as this might have compromised the DU insert in the armor array

Blame for the burnt-out status of the tanks was not placed on the ammunition but on the fuel, saying:

“It is believed that the catastrophic destruction of three of the M1A1s was due to the ignition of the fuel, and subsequently the ammunition. The intensity of the heat adjacent to the suspension-damaged M1A1 was sufficient enough to melt aluminum, and it was this type of heat which caused the fuel in the other vehicles to ignite”

Para 3: Memo to Commander 22nd Support Command, 5th August 1991

Cleanup

The day after the fire, a formal damage assessment was begun, having notified US Army Armament Munitions and Chemical Command (AMCCOM) and Army Communications-Electronics Command (CECOM) beforehand as required (due to the presence of DU). AMCCOM was to decontaminate the M1A1 tanks, and CECOM was supposed to remove them. The first week of cleanup would have to take place without any radiological support from the Army and relied only on resources from the 11th Armored Cavalry instead. For this task, 11th ACR drew on 12 personnel from 146th Ordnance Detachment Explosive Ordnance Disposal, 54th Chemical Troop (equipped with 6 XM93 Fox Nuclear, Biological Chemical Reconnaissance Vehicles) and 58th Combat Engineer Company. Access could not be gained to the site immediately due to concerns over the delayed-action artillery submunitions on both the north and south compounds, meaning the whole area was sealed off for three days. During this time, a plan of action was developed.

The large amount of unexploded ordnance of the site posed significant hazards and the personnel cleaning it up were instructed not to touch any of the DU penetrators with bare hands. Instead, they were supposed to be picked up with gloves, wrapped in plastic and then put into wooden boxes of oil-drums.

Most of the DU rounds found were located within a 120-meter radius of the three destroyed tanks, although the rounds on the ground were believed to have mainly come from the destroyed conexs rather than from the tanks. The shells within the ammunition bustle of the tanks which went off were mostly contained within that area and the compartmentalization between the crew area and the ammunition was not compromised. The majority of the damage to the tanks had actually come from the fuel-burning rather than the ammunition fire.

When the AMCCOM team finally arrived at Doha, these containers of DU were placed inside one of the burned-out Abrams tanks, and all three tanks were sent to the Defense Consolidation Facility (DCF) at Fort Snelling, South Carolina. In the meantime, marking, movement and disposal were carried out locally. Three of 54th Chemical Troop’s 6 XM93 Fox vehicles carried out radiological monitoring in the southern compound, well away from the actual DU ammunition and despite having no specific training related to DU. On 18th July, troops from 54th Chemical Troop conducted a foot-survey of radiation of the Northern compound and found no trace although the results were dubious due to the sensitivity of the hand-held equipment used.

The troops from 58th Combat Engineer Company used engineering vehicles such as bulldozers and graders to clear away the debris and ordnance in the compound without proper safety briefings as they were exposed to unexploded ordnance and even collected damaged DU ammunition without knowing they were hazardous.

To underscore the serious hazards on the site, on 23rd July, during the cleanup operation, an explosion occurred. Two senior NCO’s and a soldier from 58th Combat Engineer Company were killed when some of this ordnance exploded. In the aftermath of this, all cleanup was halted until mid-September and a new team of experts and civilian contractors were brought in.

The damaged and destroyed tanks were recovered back to the US, leaving the site on 2nd August. The remaining site was cleared. Cleanup was then passed over to the Environmental Chemical Corporation (ECC), the civilian contractors, in mid-September to finish work with around ⅔ of the compound still needing to be cleared, a process which took through November.

Lessons

Several reports followed the incident, which could have been much worse. Three troops had died during the cleanup, 4 tanks lost, 7 M109 and 7 M992 Ammunition Carriers, 4 AVLBs, and 40 or so smaller and light vehicles, such as HMMWVs, amounting to around US$23.3m (1991 values) and about US$14.7m (1991 values) worth of ammunition. An additional US$2.3m (1991 values) in damage was done to the buildings and the cleanup cost even more. For the Abrams tanks, three clear lessons stood out too. The first was the failure of the fire suppression systems which could not activate as there was no power. The second was the fire risk came not from the ammunition but from the fuel, and the final one was that compartmentalized ammunition fires could be contained to the ammunition area safely. More importantly though, was a lot of study on fire safety with munitions and containers for them, which remains a lesson to this day.

What was also left was a legacy of the damage from depleted uranium ammunition. Many troops who were there at the time or for the cleanup were exposed to depleted uranium and other chemicals, both hazardous and radioactive, many needlessly. To this day, many of these soldiers report ongoing health problems.

A US Army M1A1 Abrams, like one of the 4 that got destroyed at Doha.

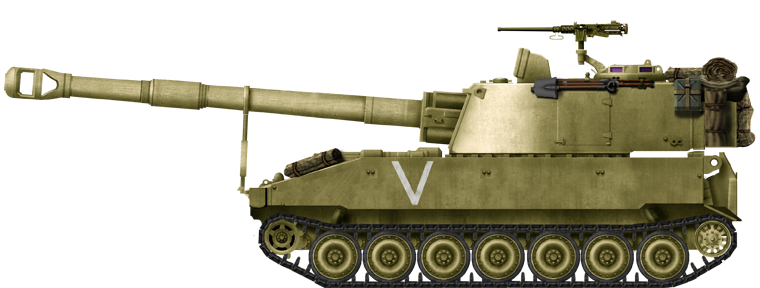

American M109A3 during the 1991 Gulf War. 7 of these were lost at Doha.

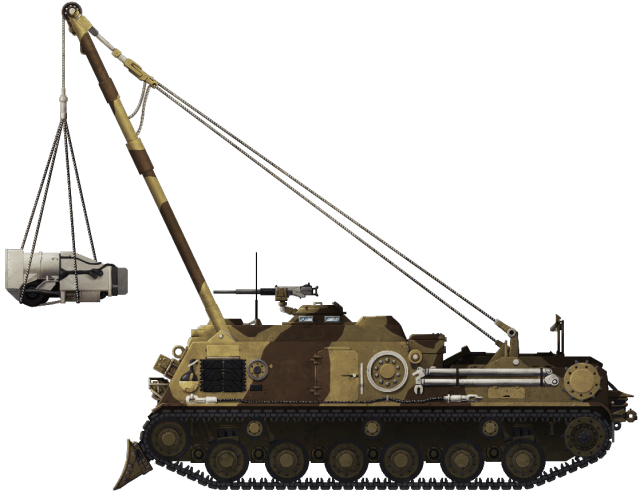

An M88A1, such as the ones that were present, but undamaged, at Doha.

Videos

Video of the fire – ammunition can be heard cooking off in the fire.

Source: John Faherty on Youtube

Video of the fire. Source: Video by Ray Hasil, uploaded by Bruce Gibson on Youtube

Aftermath of the fire (the white building in the background is the British HQ. Source: MSIAC (left) and ndiastorage (right)

Sources

Milpubblog.blogspot.com

https://gulflink.health.mil/du_ii/du_ii_tabi.htm

Doha Dash July 11th 1991 Public Facebook Group

Boggs, T., Ford, K., Covino, J. (2013). Realistic Safe-Separation Distance Determination for Mass Fire Incidents. Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division, California, USA

Lottero, R. (1998). Responses of a Water Barricade and an Acceptor Stack to the Detonation of Donor Munitions Stack. US Army Research Laboratory ARL-TR-1600

McDonnell, J. (1999). After Desert Storm: The U.S. Army and the Reconstruction of Kuwait. US Department of the Army, Washington D.C. USA

US Defense Casualty Analysis System figures 7th August 1990 – 15th January 1991 published 22nd April 2020

GAO Report NSAID-92-94. (1992). Early Performance Assessment of Bradley and Abrams.

MSIAC Ammunition Poster.

17 replies on “The Doha Disaster, ‘The Doha Dash’”

My son was there and this scares me more than a sketchy newspaper article I read then. As a mother with her son in Kuwait and no answers if he is dead or alive, and American Red Cross would not help me find answers my life was on hold until he called me two weeks later. Every parent should be informed if their child is alive.

You got it wrong when you said the 11th ACR had no part in the war. It in fact did, not as a whole unit deployment, but several troops did deploy.

Parts of the Regiment including K troop were attached to other units and served as integral parts of the entire ground war.

You do the 11th and those Troopers a great disservice by your statement.

I was there, and this brings back some horrible memories. ALLONS 🐎

I was there also! It was an event that still permanently etched in my mind, forever!

I was stationed in ASB Kuwait and was tasked as maintenance for the pressure washers and other related support equipment. I was at the wash rack area when the fire started, directly outside the effected motor pool.

Do you still have my ID card then? I was the Tank Commander of Hard Rock Cafe pictured above and had turned in my ID card at the shack for some type of wash rack equipment. I’ve never seen that ID card again.

SFC (R) Richard L. Cadwell

TC H-23 ‘Hard Rock Cafe’

Hawg Company, 2/11 ACR

Eaglehorse! Allons!

CW3 (RETIRED) JOHN LOWE

Thanks for the shout out on the pics. That was a intense day.

I arrived a few days after the explosion. Three of my EOD friends subsequently were blown up after somebody accidently kicked a white phosphorus grenade. We were tasked to collect up the DU rounds. Then another EOD friend went nuts from the losses and ended his own life. Haunts me to this day. War is tough.

I was at the Doha dash…..Spc Johnson 1/11 HHT…I was curious, what were the soldiers names that died duringt he cleanup? Wasnt the medical building named after one of the soldiers?

I was also there, I was part of the 54th Chemical troop that aided in the cleanup. Still have nightmares at times. Between that and the oil fires never was able to see some of the beautiful city. Have many health problems along with severe memory problems. Wish we had been better informed. Did I bring anything home with me?

I’m having the same issues for the same reason, I was K Troop, 3/11 ACR. I have appointments set to get checked out after Biden approved the PACT Act. Contact your VA and put in a claim to get it checked out, we fall under the Gulf War umbrella.

Watson,

I was also there with the 54th Chem Troop. If you get this message, please contact me. I was the Platoon Sgt for one of the smoke platoons.

Eaglehorse! Allons!

CW3 (RETIRED) JOHN LOWE

I was with the 11th ACR in the 511th Military Intelligence Company. One of the Units we were relieving was the 377th Combat Support Hospital out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, which was my previous Reserve unit, prior to going on Active duty.

I was with echo troop steel talons that was not a good day

My husband was a medic, and present for the Dash. About two years ago, his doctor pulled a small sliver of metal out of his back that no one knew was there. We think it might be from the headrest of the truck he was using to “ferry” people off the base.