Spanish State (1973-1974)

Spanish State (1973-1974)

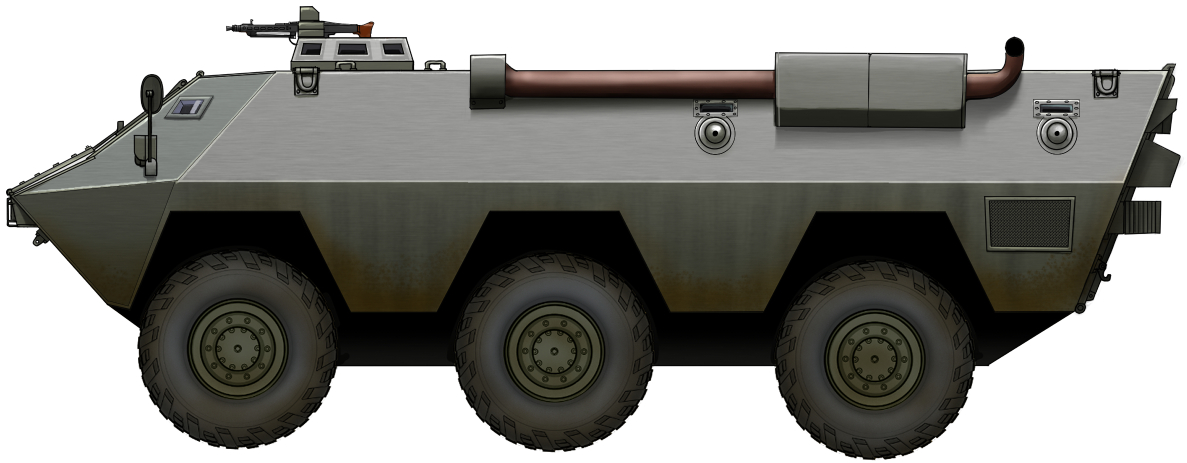

Armored Personnel Carrier – 1 Prototype Built

Perhaps one of the biggest success stories of the Spanish military industrial complex, the BMR-600, has its origins in the Pegaso 3500. A single prototype was completed in 1973 using a combination of components bought from abroad and some built in the nascent Spanish heavy industry. Shortly after completion, the only prototype, quite unglamorously, sank. Although it was recovered, testing had shown that there were some serious shortcomings that needed to be addressed before production of a serial vehicle could begin.

Context – The Spanish Economic Miracle

Following his victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), General Franco went on to rule Spain for three and a half decades with an iron fist. The conflict had devastated the country, destroying agricultural production and the already limited industrial capacity. The human cost had been immense. Mass famine and political persecution in the post-war years further diminished the population and the prospects of the people.

To make matters worse for Franco’s Spain, due to its open support of the Axis powers during part of the Second World War, Spain was isolated by the Allied powers and was excluded from the Marshall Plan and the United Nations. The Spanish State imposed a policy of economic autarky with disastrous effects.

The new geopolitical situation created by the Cold War was to change Spain’s destiny. Given the country’s strategic location at the mouth of the Mediterranean and Franco’s vehement anti-communism, the US saw Spain as a new key ally. In 1953, this new relationship was cemented in the Madrid Pact. The economic policy of autarky was abandoned in the late 1950s, as widespread change to the regime was adopted, and technocrats were given positions of power.

During the 1960s, the technocratic government reversed the situation, giving rise to the ‘Spanish economic miracle’. Between 1960 and 1973, the Spanish economy grew at an average of 7% each year. The same period saw industry grow at an annual average of 10%, as Spain moved from an agricultural to an industrial economy and society. The economic miracle also owed a lot to the growth of tourism, which remains one of Spain’s economic motors to this day. In 1960, there were 6 million foreign tourists, and just over a decade later, in 1973, this figure had leapt to 34 million.

The Pegaso 3500’s Predecessors

Spain had successfully managed to modernize its armed forces with the large influx of US vehicles that had arrived as a result of the Madrid Pact. Between 1953 and 1970, Spain received: 31 M24 Chaffees, 42 M4 High-Speed Tractors, 84 M5 High-Speed Tractors, 24 M74s, over 166 M-series half-tracks, 411 M47s, 12 M44s, 28 M37s, 72 M41 Walker Bulldogs, 6 M52s, 16 LVT-4s, 54 M48s, 171 M113-based vehicles, 5 M56s, and 18 M578s.

In spite of this, Spain was unable to prepare itself fully for the kind of mechanized warfare that had emerged during the Second World War and which had become consolidated in the early Cold War years. Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) were tested towards the end of the Second World War and would appear in large numbers during and after the Korean War. APCs were, and are, able to transport an infantry squad in the relative safety of an armored hull. In some instances, these vehicles also carry armament of their own to support the infantry dismounts.

Spain had the M-series half-tracks and the fully-tracked M113-based vehicles to perform these roles to different extents, but lacked the wheeled counterparts which would enable an even more rapid deployment of troops and quicker support across the battlefield.

To overcome this deficiency in its arsenal, during the 1960s, Spain considered several wheeled APC alternatives.

DAF YP-408

From as early as 1953, Spanish companies had had dealings with the Dutch truck manufacturer DAF (Van Doorne’s Aanhangwagen Fabriek). In 1961, the Spanish state began to carry out business with DAF directly. Although the aim of these contacts was to produce DAF military trucks under license, armored vehicles were also thrown into the mix. In 1965, a single DAF YP-408 was sent for evaluation.

The DAF YP-408 was a Dutch 8×6 armored personnel carrier. Developed in the 1950s, it was introduced into the Dutch Army in 1964 and remained in service until 1987. Like other APCs of the era, it was converted to fulfill many different roles, including ambulance, anti-tank, or command. A few also saw service with Portugal and Suriname.

The DAF YP-408 tested in Spain had the license plate ‘FS-83-64’. The trials were carried out at the Academía de Caballería de Valladolid [Eng. Valladolid Cavalry Academy] and photographic evidence suggests they were mainly to test the vehicle’s ability over uneven terrain. Regardless, no further testing was carried out and the vehicle was returned to the Netherlands.

VBTT-E4

Almost nothing is known about Internacional de Comercio y Tránsito S.A. (INCOTSA) [Eng. Commerce and Transit International Limited Company], the company that designed the VBTT-E4. They may have also previously been involved in the design of the unsuccessful Vehículo Blindado de Combate de Infantería VBCI-E General Yagüe, an armored personnel carrier/infantry fighting vehicle, and the Vehículo Blindado de Reconocimiento de Caballería VBRC-1E General Monasterio, a cavalry reconnaissance vehicle.

In the late 1960s or early 1970s, INCOTSA created the VBTT-E4. The drawings would suggest some degree of inspiration from the Cadillac Gage Commando and the Portuguese Bravia Chaimite. Each of these had a number of derivatives or variants to carry out different tasks, such as mortar carrier or tank destroyer and the VBTT-E4 was to follow this example. It is not entirely clear why the VBTT-E4 was conceived nor how Spanish military authorities reacted to it, but what is clear is that it never went into production.

Enter ENASA

In May 1962, the Spanish Army instructed Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones S.A. (ENASA) [Eng. Truck National Limited Company] to collaborate with DAF for the license production of the DAF YA-414 truck. ENASA had been founded in 1946 at the time of Spanish economic autarky. Pegaso was the ENASA brand in charge of building automobiles, including trucks for the Spanish Army.

ENASA’s DAF YA-414 production was to be overseen by a Spanish military commission. A department for military production was also to be created at ENASA. Two production stages were agreed for ENASA’s DAF YA-414, or Pegaso 3050 as it was known. A first with a petrol engine had 65% of components produced domestically. The second, with a diesel engine, had 86%. At this point, ENASA was producing fewer than 8,000 trucks, of all models, annually. A decade later, in 1973, they were producing over 20,000.

ENASA’s military department was based in Barajas, outside Madrid and near the city’s airport. Its head was José Ignacio Valderrama Curiel, and Carlos Carreras was in charge of military design. Manuel Serdá was in charge of the military design sub-department located at the Pegaso’s La Sagrera factory in Barcelona.

A Vehicle is Ordered

On March 7th 1969, the Estado Mayor Central (EMC) [Eng. Spanish Army General Headquarters] released ‘nº6-1109’, calling for the creation of a wheeled armored vehicle. Having rejected several unrecorded proposals, ENASA was given the task. The initial vague requirements set by EMC and the Alto Estado Mayor [Eng. Defense High Command] stipulated a family of 6×6 amphibious vehicles. 4×4 vehicles were rejected because of their limited mobility, whilst 8×8 vehicles were deemed too expensive. The priority was to use the fewest possible imported components in the vehicle’s construction. To this end, ENASA was to collaborate with Spanish civilian industries to develop components and solutions to build what was then known as the VERCAA (Vehículo Español de Ruedas, de Combate, Anfibio, Acorazado [Eng. Armored Amphibious Wheeled Combat Spanish Vehicle]).

Its amphibious capabilities were prioritized. Spain’s many rivers and lakes would have to be negotiated, as pointed out in an article for the magazine Ejército by Infantry Commander Mariano Aguilar Olivencia, an advocate of the VERCAA. Aguilar Olivencia also argued in favor of wheels, as he felt that tracked vehicles would suffer on the unpaved hard terrain of most of Spain. Even before a single prototype was completed, Aguilar Olivencia envisaged export opportunities and the transfer of any developed technology to future vehicles.

More momentum was gathered in June 1972 with the creation of a mixed working group within the Spanish Army headed by Colonel Antonio Torres Espinosa. Captains Ernesto Bermúdez de Castro, Javier Azpíroz Calín, and Ernesto Segurado Cabezas and three other representatives from the Cuerpo de Ingenieros de Armamento y Construcción (CIAC) [Eng. Armament and Construction Engineers Corps] were members of the mixed group. Valderrama Curiel was initially ENASA’s representative and in charge of the design team, but he died and was substituted by Manuel Seco López.

Creating a Prototype

The mixed technical working group designed a vehicle before completing a full scale wooden mock-up. Despite initial plans to construct two prototypes, only one was assembled at some unspecified date in 1973 at the Pegaso factory in Barajas (Madrid) following the specifications of scope statement ‘V-05-E’. Sources do not indicate why plans for the second prototype were abandoned.

Components for the vehicle were produced in factories all around Spain before final assembly in Barajas. Some parts, however, did have to be imported. The prototype was mechanized at Kynos’ factory in Villaverde, a neighborhood in the south of Madrid. The completed prototype was given the registration plate V-001. By this time, the name VERCAA had been changed to Pegaso 3500 or Pegaso 3500.00.

Design

External Appearance and Dimensions

Quite similar externally to other six-wheeled armored personnel carriers, the Pegaso 3500 was relatively large, at 6.93 m long, 2.98 m wide, and 2.6 m tall. Empty weight was a whopping 17.2 tonnes, increasing to 19.2 tonnes when fully loaded.

| The Pegaso 3500 compared to other 6×6 armored personnel carriers of the era | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Weight (tonnes) | |

| Pegaso 3500 | 6.93 | 2.98 | 2.6 | 19.2 |

| E-11 Urutu | 6.1 | 2.85 | 2.12 | 14 |

| Véhicule de l’Avant Blindé | 5.98 | 2.49 | 2.06 | 13.8 |

Armor

The Pegaso 3500’s armor was made from Series 7017 reinforced armored aluminum offering protection against 14.5 mm rounds. The designers made a conscious decision to use aluminum over steel as it was lighter, more flexible, and offered more interior space. To compensate for aluminum’s weaker resistance to enemy fire, the plates were sharply angled.

The sources are unclear as to which company provided the aluminum plates. Spanish military historians José Mª Manrique García and Lucas Molina Franco state that “the plates were initially provided by ALCAN and then by ENDASA”*. ALCAN was the Canadian company Alcan Aluminum and ENDASA was the Spanish Empresa Nacional de Aluminio [Eng. National Aluminum Company]. The plates were welded together onto the superstructure at Pegaso’s Barajas factory.

*“Las planchas las proporcionó inicialmente ALCAN y posteriormente ENDASA”

Engine

A diesel Pegaso 9156/8 352 hp engine is referred to in the sources. This same engine was proposed for the VBCI-E and VBRC-1E paper projects a few years prior. The 9156 was the main Pegaso engine. Used in different forms for varying purposes, Pegaso’s technical manual shows 22 different variants of the 9156, with horsepower ranging from 270 hp to 352 hp. None of these is named “9156/8”, but there are 3 which match the 352 hp: 9156.00, 9156.03, and 9156.00.25.11. Official ENASA nomenclature used full stops, not slashes for its factory designations. All three 352 hp engines were 6 cylinder diesels running at 2,200 rpm with some very minor differences in terms of fuel consumption. Sources mention that this was a variant of the commercial model that was modified to perform on steep inclines, the vehicle being designed to navigate slopes of 80%.

The engine was positioned vertically towards the front left, behind the driver’s position. The engine’s exhaust ran all the way to the rear on the left-hand side. The power to weight ratio was 18.33 hp/tonne. Maximum speed was 100 km/h and range was 1,000 km.

The gearbox was one of the Pegaso 3500’s foreign-produced components. Sources mention it was manufactured by the West German RENK Company. However, the authors contradict themselves by stating that it was the same one as used on the Spähpanzer Luchs, which used the 4 PW 95 H 1 transmission produced by ZF Friedrichshafen AG instead. Given that the serial BMR-600 also used the 4 PW 95 H 1 transmission, it is likely that this was the one used on the Pegaso 3500 prototype.

Amphibious Components

The Pegaso 3500 was designed with amphibious capabilities in mind. At the front of the vehicle there was a trim vane.

Hydrojets were installed at the rear, on either side of the access ramp, which were made, according to the sources, by a French company named Messier. They were activated by using the third gear on the transmission. The driver could apply them both at the same time or individually, to turn. Speed in the water was 8 km/h and required no preparation.

Suspension

The Pegaso 3500 had three large wheels per side with 13.00 R20 XL tires. The driver could let out air from the wheels down to 1.8 kg/cm2 to improve the drive over rough terrains. All wheels had independent steering.

Most of the suspension components were made at Farga Casanova S.A. in Barcelona. To keep the impact on the steering to a minimum, the suspension consisted of parallel triangles with hydropneumatic cylinders, providing the maximum verticality of movement.

The steering was servo-assisted rack and pinion on the first and third axles, which also had cylinders that made it possible to make it rigid from any position. The height of each cylinder could be adjusted separately, although it complicated the driver’s work. The whole suspension mechanism was the subject of a patent.

The cylinders allowed for the Pegaso 3500 to change its elevation depending on the surface it was driving on. There were four heights:

- ‘Maximum’ for traversing the most challenging obstacles

- ‘All-terrain’ for most rough surfaces

- ‘Driving’ for most roads

- ‘Minimum’ to facilitate entry and exit from the vehicle

Each side could be elevated independently, so that water that may have accumulated in the bottom could be drained out. Ground clearance on roads was 33 cm and 46 cm on rough terrain. The capability to elevate each individual wheel independently, when a tire or wheel became incapacitated, enabled the Pegaso 3500 to drive with as few as four wheels, two per side.

The Pegaso 3500 had a turn radius of 7.5-8 m.

Armament

The Pegaso 3500 was only lightly armed with a 7.62 mm MG 42 machine gun that could be fired from its position inside a cupola on the right side of the vehicle. This feature was not added until after the first tests in December 1973. The cupola had eight vision devices around it and an additional one at the front top, all designed by the state-owned small arms developer Centro de Estudios Técnicos de Materiales Especiales (CETME) [Eng. Centre for Technical Studies of Special Materials].

Crew and Dismounts

The Pegaso 3500 had a crew of just two: a driver, seated in the front left, and a machine gunner in the front right position. The driver had a large glass-protected opening in front, and two smaller glass-protected vision slits on either side. There were also two rear mirrors.

The Pegaso 3500 could carry a squad of eleven infantry dismounts. Entry and exit of the vehicle was primarily through a ramp at the rear. The ramp also had a smaller door cut into it. There was also a large rectangular hatch at the top, but this was mainly used to load and unload equipment. On either side, there were two firing slits for the infantry dismounts to fire from the inside.

Contemporary sources described the interior space as ample. There was also a radio on board, but it is unclear if it was operated by the machine gunner or one of the infantry dismounts.

Testing

The first tests were carried out during the second half of 1973 in the grounds of the Pegaso factory. The first tests outside of the factory were held on December 11th 1973, when the Pegaso 3500 was put through firing and driving trials at La Marañosa, a hilly area south-east of Madrid. On December 17th, the prototype was shown to the Alto Estado Mayor.

Journalists incidentally attending a motorbike presentation were able to view the Pegaso 3500 prototype for the first time on December 21st at the Jarama circuit. It was tested at high speeds and it easily outperformed a SEAT 1500 (a Spanish copy of the FIAT 2300 with a less powerful engine).

On December 24th, disaster struck. Early that day, the Pegaso 3500 prototype had been tested in the waters of the swimming circuit at the Pegaso factory. Later on, when carrying out a similar test at the Buendía reservoir, between the provinces of Cuenca and Guadalajara, the prototype sank. Fortunately, all the crew members were able to evacuate the vehicle.

Recovery and Rejection

Fortunately, on December 28th, sappers from the Regimiento de Pontoneros de Zaragoza [Eng. Zaragoza Sapper Regiment] recovered the vehicle. It was found at a depth of 17 m. The accident was attributed to one of the hydrojets breaking down because of a water leak into the hull.

It is unclear what happened to the Pegaso 3500 prototype in the following months. In September 1974, a mixed committee evaluated it and submitted a report to the Alto Estado Mayor. Whilst mostly positive, the report did highlight that the prototype was too large. At the time, on Spanish roads, a vehicle wider than 2.5 m had to be accompanied by a Guardia Civil [Eng. Civil Guard] car. The report recommended a reduction in size and weight and noted the need for a redesigned interior.

The next step would not be taken until January 23rd 1976, when the Estado Mayor Central published document ‘6-0199’. It praised the efforts put into creating the prototype, but rejected it, as it had exceeded the original specifications. The document also ordered the creation of new prototypes along with an updated set of specifications.

The lengthy period between decisions may be explained by events the Spanish military were involved with at the time. Pressure from Morocco in a bid to take over Spanish Sahara during the years 1974 and 1975 put the Spanish military on high alert, resulting in the deployment of a contingent should war break out. Additionally, long-serving dictator Francisco Franco’s health had deteriorated significantly prior to his death in November 1975. Given their high prestige within the regime, the Spanish military was concerned that whoever succeeded him would not maintain their status.

The next set of prototypes, the Pegaso 3560s, were ready towards the end of 1977 and the beginning of 1978. These would prove to be more successful and would lead to the BMR-600s, which entered into service in great numbers. However, these vehicles lost the amphibious capabilities that had been so important in the Pegaso 3500.

Fate

The Pegaso 3500 prototype, although rejected, was not scrapped. It remained at Pegaso’s Barajas factory until the company’s disappearance in 1990. After this, it was transferred to the installations of the Instituto Politécnico del Ejército nº1 (IPE1) [Eng. Army Polytechnic Institute No. 1] in Carabanchel, a southern suburb of Madrid. When tested, the engine still ran, but the transfer was done atop a transporter. It remained in Carabanchel until 2000. Although originally intended to be taken to a museum in Calatayud (Aragón), it ended up going to the Madrid neighborhood of Villaverde, more specifically the Escuela de Automovilismo del Ejército [Eng. Army Automobile School]. After a few years, it was once again moved to the Parque y Centro de Mantenimiento de Sistemas Acorazados nº1 (PCMSA 1) [Eng. Armored Systems Maintenance Grounds and Center No. 1], also in Villaverde, for refurbishment. Once this was done, it was to be sent to the Canary Islands.

It is unclear if the Pegaso 3500 did go to the Canary Islands, and if it did, how long it was there for. As of April 2023, it can be found at the San Jorge military base, north of Zaragoza.

Conclusion

The Pegaso 3500 was the first step towards one of the Spanish military industry’s greatest successes. Many projects had been conceived in the decade leading up, but few had materialized into even a prototype. The Pegaso 3500 showed that much work remained before serially produced vehicles could roll off the assembly line. Compared to its contemporaries, the vehicle was simply too large and heavy, with its size and weight offering no advantages. Fortunately, the future would be bright, and unlike the Pegaso 3500, it would not sink.

Pegaso 3500 Specifications |

|

|---|---|

| Length (m) | 6.93 |

| Width (m) | 2.98 |

| Height (m) | 2.6 (2 top of hull) |

| Weight (tonnes) | 17.2 empty 19.2 full |

| Armor (mm) | Unknown but resistant to 14.5 mm ammunition |

| Engine horsepower (hp) | 352 |

| Speed (km/h) | 100 |

| Range (km) | 1,000 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Infantry dismounts | 11 |

| Main armament | 7.62 mm MG 42 |

Bibliography

Francisco Marín Gutiérrez & José Mª Mata Duaso, Carros de Combate y Vehículos de Cadenas del Ejército Español: Un Siglo de Historia (Vol. III) (Valladolid: Quirón Ediciones, 2007)

Francisco Marín Gutiérrez & José María Mata Duaso, Los Medios Blindados de Ruedas en España. Un Siglo de Historia (Vol. II) (Valladolid: Quirón Ediciones, 2003)

José Mª Manrique García & Lucas Molina Franco, BMR Los Blindados del Ejército Español (Valladolid: Galland Books, 2008)

Octavio Díez Cámara, “BMR V-001, cincuenta años del blindado 6×6 del Ejército de Tierra: ¿llegará el BMR 2 español?”, Defensa.com (15 April 2023) https://www.defensa.com/espana/bmr-v-001-cincuenta-anos-blindado-6×6-ejercito-tierra-llegara-2

One reply on “Pegaso 3500”

Very interesting entre, but please note that the BMR-600 is fully amphibious.