United Kingdom (1936)

United Kingdom (1936)

Science Fiction Tank

The classic film Things to Come hit the big screen in 1936. Right at the outset of what would become WW2, this film, directed by William Menzies, predicted a devastating conflict in Europe which would last for years and destroy the very fabric of society. It was based on H. G. Wells’ science fiction book The Shape of Things to Come released in 1933.

Wells and Tanks

H. G. Wells was born in Victorian England in 1866 and went on to become one of the best known science fiction writers in history, with titles such as The First Men in the Moon (1901), The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), and the War of the Worlds (1898). Wells is also famous for his story ‘The Land Ironclads’, published in 1903 in The Strand Magazine. This fascinating piece of speculative fiction has often been seen as an influence on tank development, despite the fact the insect-like, pedrail-wheeled vehicles bore minimal resemblance to anything that saw actual production.

Much of Wells’ work involves creative visions and ideas of what the future of warfare might look like from the perspective of a man born at the height of the industrial revolution. Much of his inspiration stems from the works of earlier writers, such as Albert Robida, as well as the innovative use of armored trains during the Boer Wars in South Africa.

His prescience has, however, been seemingly overblown for this relatively minor story in a science-fiction magazine relying in part on his connection to a man like Sir Ernest Swinton, who also wrote for the magazine. This is despite Swinton himself saying it was not the reason for the invention and that it had no influence on the work. Focussing therefore on this relatively minor aspect of a long writing career has also managed to detract from his vehicles in the 1933 book The Shape of Things to Come. In the book, he says relatively little about these war machines – perhaps to the surprise of people who choose to credit him with the ‘invention’ of the tank.

Wells’ real tanks are best seen not in this book, or even in his Strand Magazine story from 30 years prior, but instead, in the film based on the book. Wells was personally in attendance during parts of the shooting, he knew the director and producer, wrote the screenplay, and had a strong personal input into all elements of the film. This perhaps explains why it is often considered a little slow and rambling, interspersed with overly long and flowery speeches from the main protagonist. But these stylistic touches extend to the visuals as well, and it is certain that Wells both saw and approved of the futuristic tank designs depicted in the film. We can therefore infer that he saw these as a better reflection of his concepts for the future of armored warfare, especially in comparison to the fanciful, insectoid machines of his 1903 publication.

In the past, many films, and especially war films, have been made with an eye for drama and messaging over the practical realities of war. The emphasis has been on the ‘human experience’ of the troops involved, or on conveying the horrors of conflict. Regardless of the precise focus of these efforts, the results are often mixed, and many miss the mark completely. However, the short war sequences in Things to Come benefited greatly from having a cast, crew, and production team made up primarily from veterans of the Great War.

The director, William Menzies, certainly knew what war looked like, having served with the US expeditionary forces in Europe in WW1. He was not alone either; the star of the film Raymond Massey was wounded in WW1 in France whilst serving with the Canadian Field Artillery. Ralph (later Sir Ralph) Richardson was too young to take part in WW1, although he did enlist in WW2 in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and train as a pilot. Edward Chapman would end up taking a break from acting and join the Royal Air Force working as an Intelligence Officer in WW2.

The Book

Published in 1933, the story was a ‘future-history’ written in epilogue as a reminiscence by a fictional character called Dr. Phillip Raven. Raven was a diplomat writing a 5-volume history from his perspective in the year 2106.

The book initially depicts a European society irrevocably torn apart by a thirty-year economic depression followed by a prolonged war. Huge strides in aeronautical engineering results in cities being devastated by mass bomber formations, causing unthinkable casualties on all sides. With their infrastructure in ruins and plagues running rampant, nations fracture and crumble back into feudal city-states ruled by local despots and warlords. Yet Wells’ narrative also details how civilisation rebuilds after calamity and slowly but surely overcomes various issues of nationalism, fascism, and religion, replacing them with a utopian vision of a world that holds science and education among its highest values. The book went on to influence other writers and science fiction, yet remains a quiet ‘cousin’ to another futurist view of a new utopia published the year before by Aldous Huxley titled Brave New World.

Nonetheless, the book was significant enough that Alexander Korda decided to create Wells’ vision on the big screen. This could have been as some kind of antidote to the even earlier Metropolis (1927) from Fritz Lange and its view of a future society divided much akin to Huxley’s Upper and Lower class stratification.

Regarding ‘tanks’ in the book, Wells makes surprisingly little mention and no description at all. There was a small reference to “the primitive tank” as a weapon in WW1 (Chapter 4), reinforcing the idea that Wells did not like the tanks the British Army was equipped with in WW1. This is reinforced by his comment (via Dr. Raven) about how “the British had first invented, and then made a great mess of, the tank in the World War, and they were a tenacious people. The authorities stuck to it belatedly but doggedly.” Though one might argue that this statement was made in-character and did not reflect Wells’ personal views, it aligned well with the British tank fleet in 1933, which consisted of an eclectic mixture of vehicles and numerous dead-end prototypes that would prove to have little military value.

“In Great Britain a group of these experts became exceedingly busy in what was called mechanical warfare. The British had first invented, and then made a great mess of, the tank in the World War, and they were a tenacious people. The authorities stuck to it belatedly but doggedly. In a time of deepening and ever bitterer parsimony their War Office spared no expense in this department. It was the last of all to feel the pinch. The funny land ironclads of all sizes these military ‘inventors’ produced, from a sort of armoured machine-gunner on caterpillar wheels up to very considerable mobile forts, are still among the queerest objects in the sheds of the vast war dumps which constitute the Aldershot Museum. They are fit peers for Admiral Fisher’s equally belated oil Dreadnoughts.”

The Shape of Things to Come, H. G. Wells (1933)

Dr. Raven’s denunciation of the parlous state of post-war British preparation for the next war follows directly on from this brief review of armored warfare in WW1, saying:

“The British dream of the next definitive war seems to have involved a torrent of this ironmongery tearing triumphantly across Europe. In some magic way (too laborious to think out) these armoured Wurms were to escape traps, gas poison belts, mines and gunfire. There were even ‘tanks’ that were intended to go under water, and some that could float. Hansen even declared… that he had found (rejected) plans of tanks to fly and burrow. Most of these contrivances never went into action. That throws a flavour of genial absurdity over this particular collection that is sadly lacking from most war museums.”

The Shape of Things to Come, H. G. Wells (1933)

Wells actually wrote rather inconsistently on tanks in his stories. In the Land Ironclads of 1903, they were the war winner, and in War and the Future written in 1917, he mused on gargantuan tanks, land leviathans literally the size of ships cruising across and crushing all before them. He built on this idea in part in The Work, Health and Happiness of Mankind, written in 1932, the year before The Shape of Things to Come. In that story, the power of the tanks was paramount, crushing helpless and hapless enemy soldiers into “….a sort of jam…” as they rolled across the land. Yet, these vehicles, the land leviathans, were now rendered helpless in The Shape of Things to Come, with the advent of poison gas and enemy minefields.

The Plot

Starring Raymond Massey as John and Oswald Cabal, Ralph Richardon as ‘The Boss’, and Edward Chapman as Pippa and Raymond Passworthy, the film was the production of Alexander Korda. Set in pre-war ‘Everytown’ (although it is meant to be London), the streets were full of gaiety and citizens enjoying their routine, from shopping at Sandersons department store for Christmas 1940. Food is plentiful, the people are well dressed and content, from the working man in his tweed flat cap to the toff in his top hat and tails leaving the Burleigh Cinema. In the background to this gaiety is the looming aspect of war, headlines about a nondescript enemy and the prospect of war with Europe rearming.

It is after Christmas that John Cabal (Raymond Massey) and Pippa Passworthy (Edward Chapman) and others are shocked by the unexpected news on the wireless; war has broken out, and the first bombs had already started falling on the city’s water works.

There follows a general mobilization and the passing of a national Defence Act. Meanwhile, the mood on the street becomes somber and gloomy as the war gets closer and closer to ‘Everytown’. Then, abruptly, the hustle and bustle of the streets is suddenly overwhelmed with a fleet of soldiers on motorbikes and the arrival of anti-aircraft guns in the square, followed soon by the shriek of loudhailers.

Here the film provides a short taste of what an air-raid by modern planes might look like – the sort of thing no Londoner would need to be reminded of in just a few years’ time. Warned to seek shelter and go home or use the underground, panic grips the streets as and our top-hatted toff shakes an impotent fist at the enemy above. Cabal is next seen in a uniform of the RAF, and in short order the first bombs start to fall. Soon the city is plunged into darkness as a blackout begins, eerily foreshadowing the darkness that would grip Britain’s own cities in just a few years. Nonetheless, the bombs still drop, obliterating first the cinemas and then the department store owned by the Sandersons.

This was a terrifying image to portray to audiences in 1936, as citizens were blown apart, vehicles and buildings were shattered by bombs, and finally poison gas started to fill the streets. Certainly, this was no light hearted or campy vision of a future being shown to audiences, but an all-too realistic look ahead to what a new war might bring them on the Home Front.

The viewer was then treated to a montage of combat made from stock footage of troops and machines, the Royal Navy at sea and excerpts of Vickers Medium Mark I tanks filmed during maneuvers. It is during this sequence and prior to the mass-bombing scenes (featuring what appear to be Lysanders) that the ‘future’ tanks are seen. These new tanks, not of a design which existed at the time, were designed to show the audience the progression of technology as the war developed.

As far as filimography goes, the air to air combat sequence which followed was certainly as good or better than some of the rather dreary contemporary films. The audience even gets to see John Cabal in action in a shiny silver open-topped Hawker Fury fighter, downing some as yet unnamed dastardly enemy who had just dropped poison gas from his Percival Mew Gull.

The time scale of the film shifts next to 21st September 1966 (also the 100th birthday of H. G. Wells). The war is dragging on and clearly things have not gone well, with rampant inflation, a shattered landscape, and the emergence of an epidemic known as the ‘wandering sickness’.

It is this wandering sickness which propels the new chapter, with Ralph Richardson as ‘The Boss’. He portrays a vicious and pompous warlord who rises to power by ruthlessly executing those unlucky enough to be struck with the wandering sickness.

By 1966, the only functional parts of society are the military and, amusingly, the fashion industry, as citizens walk dressed in rags or stereotypical Romani costumes, while still sporting immaculate hairstyles carefully slicked back by the generous application of Brylcreem. The people at this time are also half-starved – a stark contrast to the halcyon pre-war days of a well-fed populus. The wandering sickness meanwhile continues to ravage society, taking until 1970 to finally peter out.

All this time, the people remain at war, although maybe not the same war they started, for the enemy is now as much rival towns over resources, such as ‘the hill people’ and the nearby coal mines, as much as any ‘foreign’ foe. Here, ‘The Boss’ brings his army to the fore to seize the coal mines so he can make petrol and get his planes into the air.

Source: Things to Come.

The Boss’ plans are thrown off by the arrival of the ludicrously-large helmeted and now gray-haired John Cabal in a modern aircraft, bringing news of a new organization. This harkens back to the idea of the League of Nations, but perhaps is closer to the post-war concept of the United Nations, albeit known by the unusual and not very intimidating name of ‘Wings Over the World’ (W.O.T.W.).

Cabal brings this news to ‘The Boss’, who imprisons him until a message of his capture can be taken to W.O.T.W. W.O.T.W.’s reply is succinct yet definitive, coming as it does in the form of a fleet of giant bombers, who proceed to drop bombs full of sleeping gas on the uncivilized masses thronging the ruins of Everytown. The people are saved from starvation, poverty, and the untidily dressed, at the cost of a single human life, as the Boss expires helplessly on the steps of the city hall. The arrival of the W.O.T.W. heralds an end to the new dark ages, promising an end to disorder and chaos.

In the aftermath of the end of this barbarous time, Cabal makes one of those ‘trying-a-bit-too-hard-to-be-inspiring’ speeches followed by another montage. This time, it is the progress of science as the Earth is mined ruthlessly for its hidden resources, leading to the bright new future and featuring giant tracked machines blasting away at the rock.

This future of 2036 is decidedly whiter, cleaner and less Romani-esque than the age before. Cloaks, short shorts, and the same slicked back hairstyles dominate as progress reaches the point where man is to travel to the stars. This journey to the stars is courtesy of a giant gun hundreds of stories high used to launch one man and woman into the future.

Those two characters are the children of Oswald Cabal and Raymond Passworthy and the launching has to be rushed to avoid destruction by the modern anti-science, anti-progress, populist luddites led by an artist called Theotocopulos (played by Cedric (later Sir Cedric) Hardwicke – also a veteran of WW1).

The film ends with the firing of the gun as the angry luddite-mod led by Theotocopulos storms the gun and are presumably killed or otherwise rendered even more senseless by the great concussion of it propelling the new Adam and Eve to the stars to conquer the Moon.

Yet another great speech from Cabal brings the movie to a close and, as sentimental as some of it may seem, the motives expressed were clearly real – a drive for science and progress to never stop, for man to never quit dreaming of the future and greatness, and that humans, as small, feeble, and fragile as they are, can conquer any adversity. Certainly very noble attributes with lofty goals for the film and inspiration for the struggle to come in just a couple of years.

The film itself was well funded, costing over GB£300,000 to produce – this was the equivalent of US$1m in 1933 and in 2021 would be the equivalent of GB£22.8m (US$28.5 m) accounting for inflation. It ‘predicted’ a few things that, in 2021, we take for granted, from helicopters to holographic projection and the flat screen television. It did not, however, predict a good showing at the box office.

Source: The Criterion Collection

The film was not a commercial success and has lapsed in copyright. It is now in the public domain and can be watched online on a variety of platforms for free, although some versions are of a second rate quality copied from old videos or discs. The Criterion Collection offers a version of DVD with added extras, such as another montage showing the construction of the great underground city, which is not found on other releases.

The ‘Future Tank’

Appearing for just a few seconds during the film, the ‘future tank’ is little more than a model. In other instances, some random ‘tank’ model from a film would garner little interest, more so if it was science fiction. The tank presented in Things to Come, however, stands out. This was not the random thought of a model maker, but a film based on a book written and filmography approved by H. G. Wells. If Wells occupies any position in ideas of armored warfare before WW1, then his interwar idea of a tank must be taken into account in no less detail.

Sadly, with just a few seconds of footage and no substantive description from the book on which the vehicles were based, all that can be gathered as information is from the model as presented (and approved by Wells) in the film.

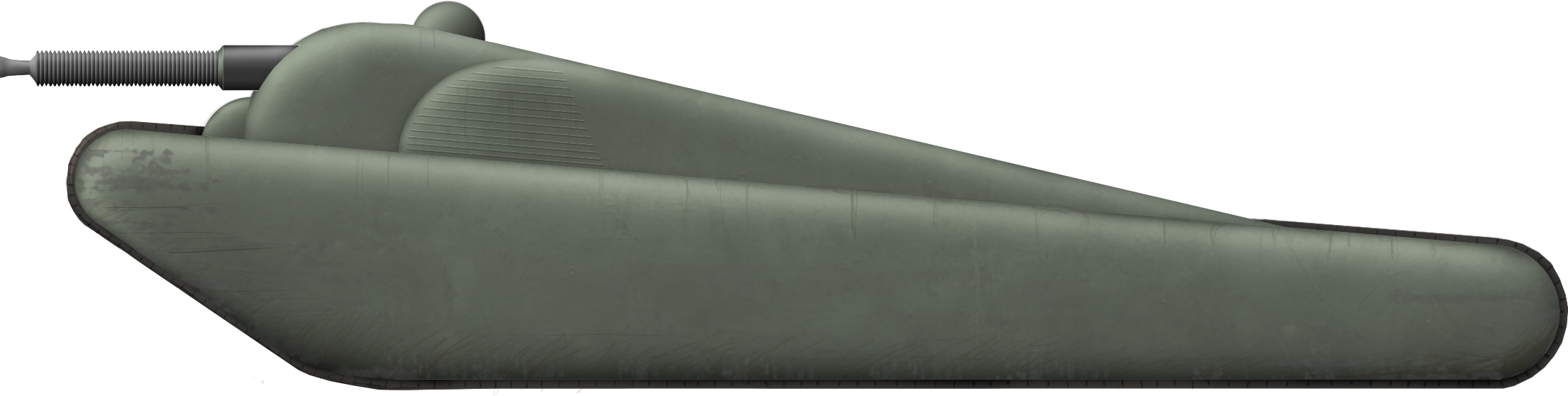

From the brief screen appearance, a sleek and rounded vehicle is apparent. Running on a pair of tracks made from what appears to be rubber, the rounded track runs flush to the body, extending out over the sides. The track shape is roughly that of a long obtuse triangle, with the top of the track run as the long side tapering down to ground level to meet the second-longest side which is in contact with the ground. The third side of this triangle is the shortest and creates the attack angle at the front, allowing the vehicle to climb obstacles.

There are no features within the triangle made by these tracks other than the rounded projection of what can be assumed to be armor covering the suspension or drive components which would have been underneath. Between the horns of the tracks, the hull is noticeably heavily rounded and curves down between them without connecting to the front horns of the track. On the front of this rounded front hull is a semi-spherical projection, the prospective function of which is unclear.

With the track horns projecting forwards in a manner reminiscent of the later A.22 Churchill tank, this would indicate that, if this were to be a functional vehicle, then it would have to have the drive components, like sprockets at the back rather than at the front.

The hull, above the tracks, is likewise tapering to the back and is a simple doorstep-wedge shape, albeit heavily rounded and surmounted at the apex of the ‘wedge’ by what appears to be a small round cupola.

On the well-angled right hand side of the upper hull (and presumably duplicated on the left hand side as well) is a large semicircular vent running the full height, from the top of the track to the top of the wedge. It is unclear if this vent is meant to be something for the crew or engine, but the size would indicate that it is more likely intended to convey an air intake for a combustion engine, presumably located within the tapered back half of the tank.

In terms of size, there is little from which to judge the proposed size of this tank other than the landscape scene, where they are driving across fields and the view of it crushing a building. Assuming the model brick building being deployed in the sequence was meant to indicate a normal two story dwelling or shop, this would make the vehicle not much bigger than a ‘normal’ tank of the era, at approximately 4 m high. Assuming the vehicle to be 4 m high, the tank would be around the same width and somewhere around 8 m long.

The dominant feature at the front of the hull is the gun. Like other features, there is nothing to go on other than the model. The primary tank gun for the British Army in 1933, when this film was made, was the 2 pdr. gun. This was an excellent gun for knocking holes in armor and was still in frontline service on some armored vehicles through 1945. It is not, however, the gun on this tank. As shown in the model, the gun is long – projecting maybe a quarter of the height of the vehicle forwards, which would mean a projection of around a meter. It is also substantially larger in terms of bore and barrel thickness and is perhaps meant to convey some kind of heavy howitzer rather than a high-velocity anti-armor gun.

Conclusion

Whilst the film itself was not a commercial success, it is a classic pre-war science fiction film in the truest sense of the word, alongside Metropolis (1927). The ‘prediction’ elements of the film are perhaps a little overblown, in the sense that many people in the 1930s could see another war, especially after the rise of Hitler in Germany. Wells perhaps is the most notable of these and, in terms of tanks, the vehicles shown in the film are clearly indicative that, whether or not he felt they were limited (by gas and mines), or some unstoppable leviathans, they would have a place in the forthcoming war. In this, he was undoubtedly correct and, dying in 1946, he got the chance to see this new war run to fruition, not with the collapse of society during a never ending war, but with Victory over Germany and its allies. Further, he got to see the development of tanks as well, and may have taken some satisfaction that the pre-war vehicles (such as the Vickers Medium Mark I) featured in the film, which were unsuitable, were quickly eclipsed and replaced.

Sources

Arosteguy, S. (2013). 10 Things I learned: Things to Come, The Criterion Collection https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2811-10-things-i-learned-things-to-come

British Film Institute biography of Charles Carson http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/individual/14382 archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20090113202151/http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/individual/14382

O’Brien, G. (2013). Things to Come: Whither Mankind?, The Criterian Collection https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2812-things-to-come-whither-mankind

Stearn, R. (1983). Wells and War. H. G. Wells’s writings on military subjects, before the Great War. The Wellsian New Series No.6, UK.

Stearn, R. (1985). The Temper of an Age. H. G. Wells’ message on war, 1914 to 1936. The Wellsian, Volume 8, UK.

Things to Come at IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0028358/

Wells, H. (1933) The Shape of Things to Come. Delphi Classics reprint (2015)., UK.

One reply on “Tanks from The Shape of Things to Come”

I was recently looking up some information on classic American industrial designers, and it appears that Norman Bel Geddes assisted with the film. Considering the man’s interest in war-gaming, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the tank pictured was basically his concept. At least it’s another avenue of research.