France (1938-1940)

France (1938-1940)

Anti-Tank Gun – Unknown Number Built

The French Army started to experiment with armor-piercing weapons as early as the Great War. During the German offensive of 1914, a vastly overestimated armored car scare led to the French army mobilizing naval 47 mm guns for anti-armor work, notably creating the Autocanon de 47mm Renault. The entrenchment of both sides as 1914 morphed into 1915 put an end to this armored car scare. Later in the war, as tanks became an actively used weapon, countering them became a source of worry again. The vehicles were first employed by France’s ally, Britain, and then by the French themselves, before the Germans would be able to produce and employ their own. But the possibility remained there, and the German Army would also widely use captured British tanks. As such, a number of options were studied as early as 1917 or 1918. This included some infantry support guns which were hoped to also fulfil an anti-armor role, such as the ill-fated American-made 37 mm Bethlehem Steel gun, or the mounting of the ubiquitous 75 mm modèle 1897 gun on a wooden platform which guaranteed high lateral traverse. In the last weeks of the conflict, the French tested what appeared to be a more mature and potent solution to the problem of enemy tank, the 17 mm Filloux, a high-velocity (1,000 m/s) anti-tank gun firing a small caliber, 17×209 mm semi-rimmed cartridge, mounted on the carriage of the very common 37 mm TR modèle 1916 infantry support gun.

The conclusion of the Great War would result in the threat of enemy armored fighting vehicles being vastly less urgent, and likely due to less interest from a scaling-down military, the 17 mm Filloux would not go anywhere. Nonetheless, studies on the matter of anti-tank guns continued in France. While a curious Delaunay-Belleville DB20 20 mm weapon, seemingly sometimes called an “anti-tank machine gun”, was offered in a similar timeframe or soon after the Filloux, it was not adopted either.

In 1921, France launched a program that envisioned both a 10 to 15 mm dual-purpose anti-tank and anti-aircraft machine gun, as well as a dedicated high-velocity anti-tank gun of a caliber smaller than 37 mm. This program would fail to result in the adoption of an anti-tank gun. The machine gun requirement would result in a 13.5 mm MAC dual-purpose prototype and later the 13.2 mm Hotchkiss, which was used strictly in an anti-aircraft role. Meanwhile, in 1927, the state workshop of APX (Atelier de Constructions de Puteaux – Puteaux construction workshop) offered a 20 mm anti-tank gun. The caliber was found to be too small to result in sufficient armor-piercing capacities. New specifications requesting a 25 mm semi-automatic gun were issued in 1928. Prototypes from both APX and Hotchkiss would be pursued. The Hotchkiss design would finally be adopted in 1934. One can lament how the French Army had the conceptual requirements for an anti-tank gun as early as 1921, but would only be able to start issuing one in the middle of the 1930s.

The 25 mm Hotchkiss

The 25 mm anti-tank gun the French army adopted in 1934 was a potent gun. While small in diameter, its long, 72 caliber barrel granted a high 950 m/s muzzle velocity to its 25×193.5 mm rimmed tungsten core projectiles. Able to penetrate a 40 mm plate at a perpendicular angle and a range of 400 m, or a 32 mm plate at an angle of 35° and a range of 200 m, the gun would have had little issue dealing with most tanks used in the mid-1930s.

Nonetheless, some aspects of the Hotchkiss gun, especially those concerning the shield and carriage, betrayed its 1920s conception. Despite its small caliber, the 25 mm SA 34 was still a fairly heavy piece, at 480 kg in battery. This would prove an issue when manoeuvring the gun around. During traction, it also meant that towing the gun with a single horse would be quite slow and tiring for the animal. On the topic of traction, the gun also suffered as it had no suspension. As a result, it could only be towed at slow to moderate speeds. When adopted, the French Army regulations stated the gun could be towed only at a maximum of 15 km/h on a good road, 10 km/h on an average road, and 6 km/h on cross-country. After a little under 2,000 guns had been produced, modifications allowed the traction speed to rise to 35, 20, and 10 km/h respectively, which was better, but still not particularly fast. In other words, while it offered a modern and potent weapon in terms of ballistics, the carriage of the 25 mm Hotchkiss could still be improved in order to make the operation of the gun easier.

APX Works on Hotchkiss’ Gun

Upon adoption of Hotchkiss’ gun, the issues of weight and traction were not entirely out of the French Army’s consideration. As early as the adoption of the gun, APX’s engineers were asked to try and come up with a lightened design which would be easier to move around.

APX, having taken part in the competition that resulted in the adoption of the Hotchkiss gun with their own prototype, quickly came up with a modified version of the 25 mm anti-tank gun. The APX-modified Hotchkiss design offered a first prototype in 1936, though it differed significantly from the definitive model adopted in 1937. Compared to the original gun, the APX SA-L 1937 managed to massively lower the weight from 480 to 310 kg while keeping identical armor-piercing performances. The adoption of a new, simpler shield design contributed to the weight loss. However, the main reduction was with the use of a 193 kg carriage instead of the 386 kg on the Hotchkiss 25 mm SA 34. As a result, the gun was more fragile, and was strictly prohibited from motorized traction. Strict orders were given for it to only be transported under by horses, at maximum speeds of 15 km/h on a good road, and 10 km/h cross-country. Nonetheless, the weight losses were still significant, and the APX-modified gun was adopted as the 25 mm SA-L 37 (25 mm Semi-Automatique Allégé modèle 1937 – Eng: 25mm, semi-automatic, lightened, 1937 pattern) and entered production alongside the Hotchkiss gun.

Putting the Same Men at Work, Under a New Employer

While the French Army put APX’s engineers to work on a lightened version of the Hotchkiss gun, this did not mean that the original Hotchkiss designers were not put to work on improving their design either.

In 1936, the new left-wing government of France, known as the Popular Front, led massive nationalization of the French armament industry, with the desire to put this critical sector under the control of the state rather than private companies. In this context, the armament factories of Hotchkiss, in Levallois-Perret, were nationalized in August 1936.

The engineers at Levallois likely started to work on an improved version of their anti-tank gun at an earlier point. Unlike APX, they opted for a different solution on how to improve the 25 mm anti-tank gun. While still aiming to lighten the gun to an extent, another equally important goal was to enable high-speed traction on the new design. The first clear trace of an improved 25 mm gun from Levallois is dated from February 24th 1937, when the factory confirmed the improved anti-tank gun it was working on would be finished soon. In practice, however, it would be another year and a half before a prototype of the improved 25 mm anti-tank gun from Levallois would be put to trial. The improved gun would begin experimentation on July 12th 1938.

Design of the Levallois 25 mm Lightened Anti-Tank Gun

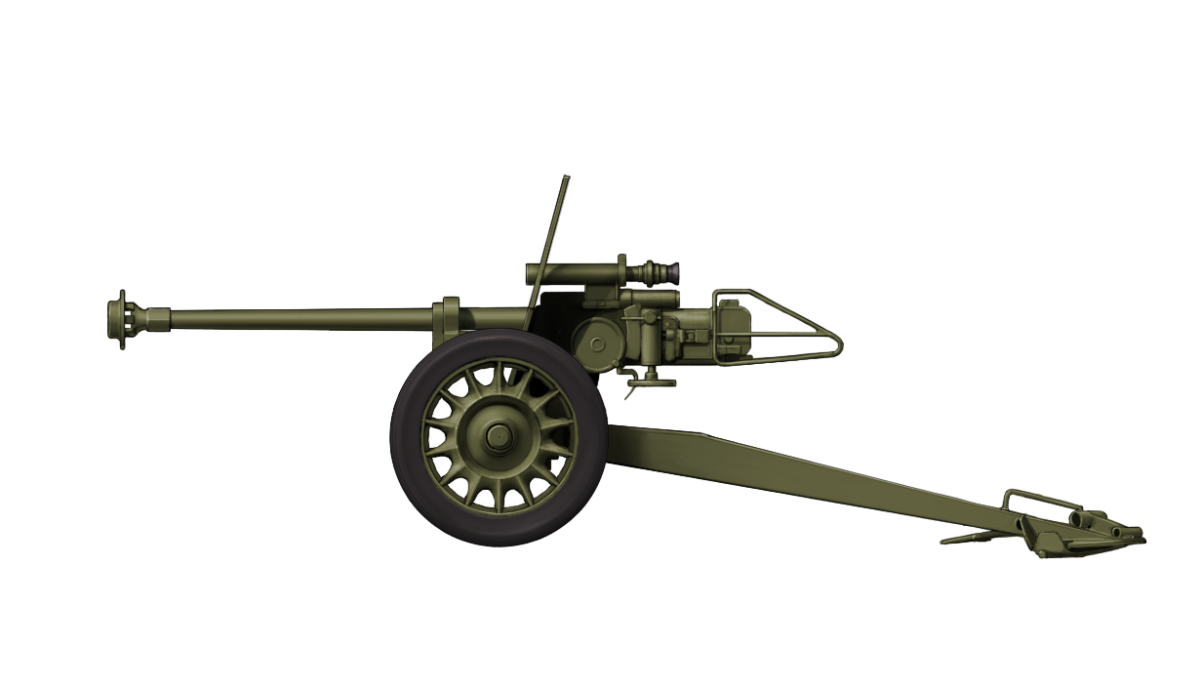

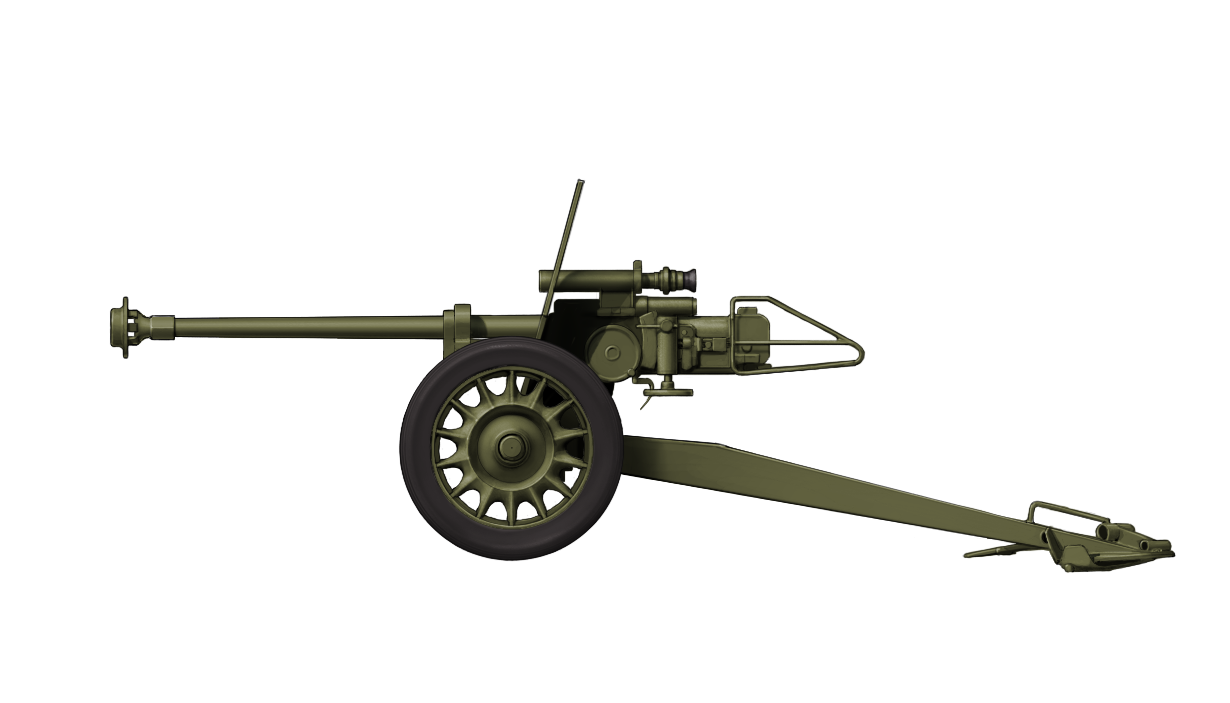

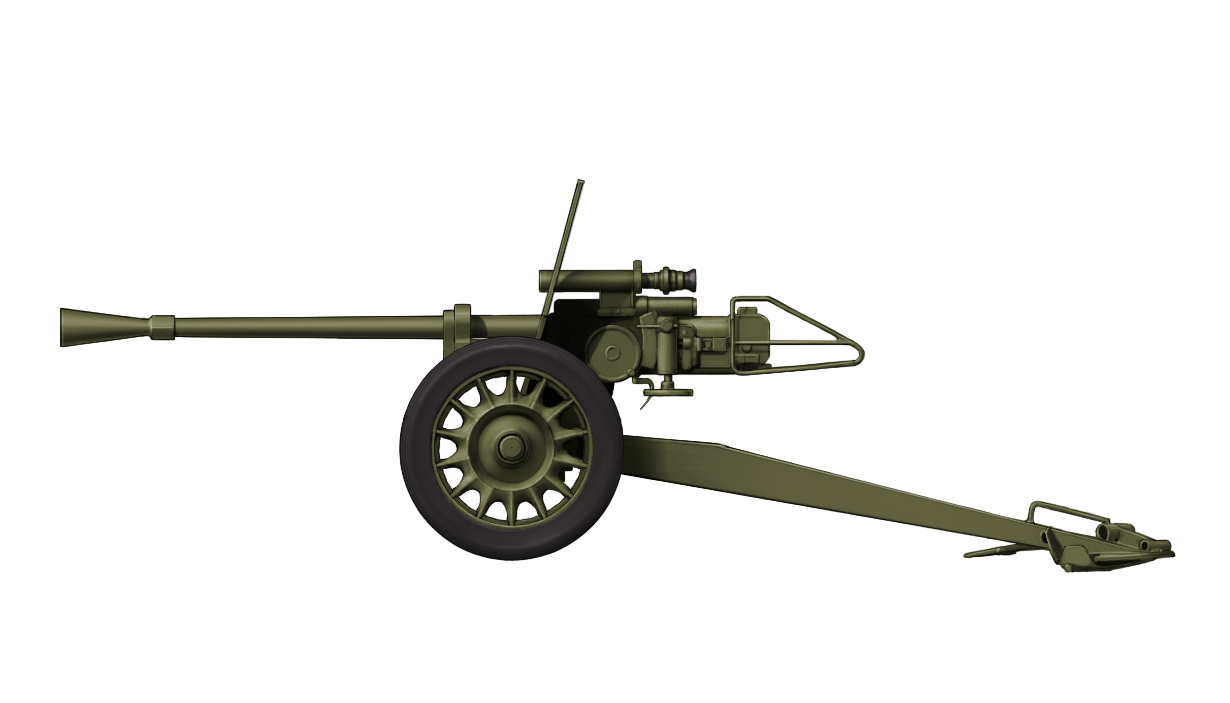

The prototype appears to have been, by this point, known as the Canon de 25 SA allégé (Eng: Lightened 25 SA gun, SA standing for Semi-Automatic) or Canon de 25 mm SA Hotchkiss adapté à la traction rapide (Eng: Hotchkiss 25 mm SA gun modified for rapid traction).

Some very significant modifications had to be undertaken around the carriage in order both to lighten the gun and allow high-speed traction. Likely, the most significant was the addition of a suspension. The gun used wheels fairly similar to those used on the APX SA-L 37. These were aluminum wheels with 14 ribs and holes separating each of these in order to lose weight, with pneumatic 67 cm in diameter tires. These wheels were mounted on a deformable axle mounted on springs. The carriage retained a split-trail, which would automatically lock the suspension when deployed.

A number of additional changes were made to the gun in order to lighten it. Most of these involved using thinner construction for elements, such as the split-trail, as well as lighter steel. This lighter construction material was notably used in the elevation and rotation wheels as well as sight holder. The complex multiple-piece shield of the 25 mm SA 34 was ditched and replaced by a much simpler and thinner one-plate shield, with an opening to the top right of the barrel through which the sight would be placed. The thinner thickness of the shield was compensated by it being angled further back, with an incidence of 30° in comparison to 15° on the SA 34. The shield offered less protection to the gun’s crew in comparison to the 25 mm SA 34, but this was deemed an acceptable loss.

There were also some modifications unrelated to the weight of the gun itself. The traverse and elevation mechanisms of the gun were now locked when in travel mode. However, the gun was also modified so that it could be aimed, traversed and elevated without deploying the split-trail if need be. The four contact points of the gun with the ground, aka the end of the split-trail and the wheels, were revised in order to ensure greater stability. The modified gun also removed the pistol grip featuring a trigger present on the original gun. Instead, the trigger-lever was found under the carriage. A firing mechanism was also added to the traverse wheel.

Dimensions wise, the gun was fairly similar to the 25 mm SA 34, with slight differences. It had a width of 1.13 m, a total length of 3.46 m in travel mode, and a height of 1.08 m. The lateral traverse was identical to the 25 mm SA 34, with 30° to either side, giving a forward 60º field of fire. The elevation and depression were -5° to +15°. In terms of weight, the gun was 110 kg lighter in battery, at 370 kg. The gun itself was barely lighter, at 89 kg in comparison to the SA 34’s 90 kg. The weight reduction had largely been carried out with the carriage, which went from 386 to 281 kg, and the shield, which went from 75 to 38 kg. There were little to no modifications in the design of the gun itself. It retained the same 25×193.5 mmR cartridges, the same L.711 sight, and a similar semi-automatic breech granting a theoretical rate of fire of around 30 rounds per minute, and a more practical one of 15 to 20.

Trials and Modifications

Trials began in July 1938 at the Etablissement d’expériences techniques de Versailles or EETVS (Eng: Versailles Technical Experience Establishment). These trials included the firing of 500 projectiles, and being towed by motor vehicles for 500 km in varied terrain and then 3,000 km on roads.

Mobility-wise, the gun performed very well. The said distances were crossed at an average speed of 55 km/h, and sometimes peaking at up to 85 km/h. The suspension was found to perform very well and make the gun easy to move around across all types of terrain and by all types of vehicles, including Renault UE tracked tractors, lorries, horses, and likely half-tracks. The only issue found was light damage on one of the wheels, which was not particularly out of the ordinary after such distances were crossed. The mobility of the gun, when moved around by its crew in the field, was also tested. The gun was subjected to comparative trials against the 25 mm SA 34. Both guns were carried around by a five-man team through 200 m of varied, cross-country terrain. The team moving the Levallois lightened gun around were found to cross this distance in 3.25 minutes and still be in good shape at the end of it, whereas the team moving the 25 mm SA 34 around needed 6.05 minutes to cross the same distance and were exhausted by the end. These good performances would result in it being rated for 70 km/h on a good road, 40 km/h on an average road, and 15 km/h cross-country. Seeing as the gun was towed around at 85 km/h without issue during trials, it is likely these regulations were conservative to an extent.

While, mobility-wise, the gun was excellent, there were some issues when firing. The lighter construction of the gun led to an increase in recoil. While the movement of the gun backward was the same as on the 25 mm SA 34, at 240 mm, it was felt more strongly. This was found to be a particularly negative issue during the first few shots taken in a new position, when the gun was still ‘anchoring’ itself in the ground. At these moments, a gunner would have to remove their eyes from the sight before firing, taking the risk of light injury around the eye if this was not done. This was obviously not judged as acceptable by the trials commission, which sent the gun back to Levallois for a few days so modifications could be undertaken during the trials. The solution by Levallois’s engineer was to remove the flash hider, similar to the one found on the 25 mm SA 34, and replace it with a circular muzzle brake. This proved sufficient to reduce the recoiling length to 200 mm and solve any issue with the gun potentially injuring its operators during recoil.

There were still some minor issues with the gun. The addition of a muzzle brake was found to result in some projections of dust, small rocks, or mud towards the crew, particularly when the barrel was particularly close to the ground, as could be the case in fortifications. The trigger configuration was also found to be inferior to the 25 mm SA 34, of which the pistol grip was dearly missed. However, it was also found to have a number of advantages. Performance-wise, it was very similar to the 25 mm SA 34, but putting the gun in battery, or out of battery, was a much easier and less effort-intensive task for the crew. When maneuvering the gun around, the weight carried by each crewmember was found to be of 17 kg, while it would have been 33 on the 25 mm SA 34. These advantages were judged sufficient by the trials commission tasked with testing the gun to deem it “un bon matériel de guerre” (Eng: A good wartime piece of equipment). On January 10th 1939, the French Direction of Infantry formally adopted the gun as the Canon de 25 mm SA modèle 1934 M.39 (Eng: 25 mm SA gun 1934 pattern M.39, with M.39 standing for modifié 1939 – modified 1939)

Elements similar to the 25 mm SA 34

The exact anti-armor performances of the 25 mm SA 34 M.39 are not known. However, we know they were close enough to the 25 mm SA 34 to the point where the need to report them was not felt. Trials of the Balle P anti-armor projectile on the 25 mm SA 34 indicated a penetration of 40 mm on a vertical steel plate at 500 m, and 32 mm on a plate at an angle of 35° and a range of 200 m. German tests performed with captured guns give a more extensive range of values. Against a vertical plate, the shell penetrated 47, 40, and 30 mm of armor at 100, 500, and 1,000 m, respectively. At 30°, the penetration values were 35, 30, and 20 mm. Finally, at 45º, they were 18, 16, and 15 mm.

The sights used on the 25 mm SA 34 and on the M.39 were the lunette L.711 APX modèle 1936, which offered a 4x magnification, 11° field of vision, and markings for firing at up to 3,500 m. It was not fixed to the carriage, and was carried in a separate case. The opening to insert the sight into was found on the top right of the barrel.

The crew of the 25 mm SA 34 and of the M.39 would comprise six: a commander, a gunner placed to the left of the gun, a loader placed on the right, and three additional gun crewmembers. If the gunner was knocked out, their replacement was the loader, and if the loader was knocked out, they were replaced by the second spare crewmember, who otherwise cleaned and handed over the 25 mm cartridges from the crates. In practice, the gun could remain reasonably effective with two crewmembers, and still be operated, albeit with a much lower rate of fire, by a single crewmember.

Production Schedule

The modified gun was adopted in January 1939 and, in long-term planning, was intended to replace the 25 mm SA 34 on the production line, and eventually in the army. However, switching the production lines to the new gun would take some time. – By Spring 1940, production of the 25 mm SA 34 was still in full swing and even increasing.

It does appear that a few pre-production 25 mm SA 34 M.39 pieces may have been completed. According to one report, two guns were in service, likely for experimental purposes, within the 1ère Division d’Infanterie Motorisée (1ère DIM) (Eng: 1st Motorized Infantry Division) on April 1st, 1940. No view of these guns has ever emerged, and as such, their existence remains hypothetical and should be treated as such. The gun was intended to be distributed in priority to motorized unit, such as the BCPs (Bataillon de Chasseur Portés – Eng: Motorized Chasseurs Battalions), CDACs (Compagnie Divisionnaire Antichar – Eng: Divisional Anti-Tank Company) and motorized infantry regiments. In the meantime, the prototype was still being used experimentally, with the last known firing trials being held as late as May 7th, 1940.

Deliveries of the first production examples were to start in June 1940, with the first 50 examples scheduled to be delivered during this month. What eventually befell these is unknown. The facilities of Levallois would have been taken, alongside Paris, on June 14th. In previous decades, there were some rumors that up to 400 may have been completed, but more recent research has disproven such claims. Currently, uncertainty exists as if some may have even been fully completed. If so, they likely saw little to no operational use, or may even have been captured intact before delivery by German troops. If they indeed existed, the two pre-production guns part of the 1ère DIM may very well have fought, seeing as the division was engaged, and later annihilated, in the French manoeuver to safeguard Belgium and the Netherlands, Plan Dyle-Breda, ending in the encirclement of much of the best elements of the French Army, the British Expeditionary Force, and the Belgian Army around Dunkerque.

Conclusion – The Last Evolution of the French 25 mm

The Canon de 25 mm SA modèle 1934 M.39 was the most advanced model of the French 25 mm gun. When comparing it to the standard gun adopted in 1934, its operation would generally be easier due to a suspension and lighter weight which granted the gun a much better mobility, either when being towed behind a horse or vehicle or when being moved around by its crew in the field. Performance-wise, the gun was identical to the standard 25 mm, which proved adequate during the 1940 campaign.

One can still raise questions on how long the new 25 mm would have remained a useful piece of equipment. The issue with such a low-caliber is that, as the war went on, creating more powerful ammunition would likely have proven to be a struggle. As a matter of fact, as early as 1940, studies for Brandt sub-caliber ammunition which would highly improve armor-piercing performances were underway for a number of calibers. These included the French 37 mm or 75 mm, as well as 155 and 203 mm calibers for the navy, but, crucially, none appears to have been considered for the 25 mm. As such, it is likely the gun would slowly fall into obsolescence in the coming years, even if it was actually produced. While some small-caliber armor-piercing weapons, such as Soviet 14.5 mm anti-tank rifles, proved to remain useful for the duration of the war, albeit typically not as much as in the its early phases, these were typically man-portable anti-tank rifles which would be far easier to move around to target the sides and other weak areas of a tank’s armor coverage than a field gun, even a particularly light and mobile one.

| Weight (Deployed) | 370 kg |

| Length (With Carriage) | 3.46 m |

| Height | 1.08 m |

| Width | 1.13 m |

| Maximum towing speed | 70 km/h (good road) 40 km/h (average road) 15 km/h (cross-country) |

| Caliber | 25 x 193.5 mm |

| Traverse | 60° |

| Elevation | -5° to +15° |

| Rate of fire | 8 – 20 rpm, up to 25 rpm with a well-trained crew |

| Sight Range | 3,500 m |

| Effective range | 800 m |

Sources

GBM n°97, Juillet-Août-Septembre 2011, “Les canons semi-automatiques antichars de 25 mm Première Partie: Le canon de 25 mm SA modèle 1934”, Eric Denis et François Vauvillier, pp 86-95

GBM n°98, Octobre-Novembre-Décembre 2011, “Les canons semi-automatiques antichars de 25 mm Deuxième Partie: Les dérivés du 25 mm SA modèle 1934”, Eric Denis, pp 28-31

Notice sur le canon semi-automatique “Hotchkiss” de 25mm du 2 Janvier 1935, in its 1937 edition, by the Ecole Militaire & d’Application de la Cavalerie et du Train via Wikimaginot