Austro-Hungarian Empire (1901)

Austro-Hungarian Empire (1901)

Artistic Representation – None Built

Does life imitate art, or does art imitate life? The answer is that both are true to one extent or another. In the age before tanks and at a time when even armored cars were very much in their infancy, there were many ideas about new weapons of war and armored vehicles. Some of these were serious ideas submitted to governments and armies, some never left the patent office, others were the whim of newspaper artists. One particular writer who gets a lot of attention is H. G. Wells, who wrote ‘The Land Ironclads’ in 1903 and has been seen by many as somehow predicting armored warfare. Two years before Wells, there was another fantastical creation for a war machine, one submitted without publication in a popular periodical of the day and without a back story. This was a simple drawing of a vehicle and might just be ‘art’ to some, but in 1901, this was also a vision of the direction warfare would be heading in just a few short years. This is Alfred Kubin’s ‘Der Staat’.

It is difficult, maybe impossible, to accurately catalog every single concept, idea, design, plan, or suggestion about armored warfare prior to 1916 – the year the first tanks appeared in war. Certainly, there had been plenty of such ideas going back over the preceding century and they exist in various degrees of seriousness as designs. The first real ‘modern’ armored vehicles would, however, not appear until the turn of the century with vehicles such as Simms’ War Car (1899 – 1902) and the Fowler B5 Armoured Road Train (1899 – 1901).

These vehicles, however, would not capture the public imagination for armored warfare quite like H. G. Wells managed with his short story ‘The Land Ironclads’ in 1903. Published as science fiction, it is seen by many as popularizing the ideas of armored warfare. If, however, any credit can be given to Wells for what was just a short story, then the same courtesy and attention needs to be extended to other artists and writers. One to meet that criteria was Alfred Kubin, who drew an armored fighting vehicle in 1901.

The Man

Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877 – 1959) was an artist and writer. Born in Leitmeritz, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the town is today known as Litoměřice and is part of Czechia. By age 3, he was living in Salzburg, Austria, and then moved to Zell am See.

Source: Wiki

Throughout his life he produced art, although he is considered an important figure primarily in the fields of Symbolism and Expressionism. Kubin in many ways epitomizes the idea of the tortured artist. His work is often dark and brooding with a focus of distorted twisted animals, female sexuality, and imagery of death and suffering. He even attempted suicide at his mother’s graveside in 1896 during a mental health crisis which led to him being invalided out of the Austrian military in 1897.

After this short stint in the Austrian military, he went to the Munich Academy to study in 1899 but still struggled with his mental health, suffering a breakdown in 1903. Despite these health problems, he would go on to be part of the Avant-Garde art movement and exhibited work in Berlin and Munich prior to World War 1, as well as providing illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Despite his brief time in the military, Kubin served in neither WW1 nor WW2 and his contribution to military matters appears to consist of a single image he produced in 1901, titled ‘Der Staat’ (English: Government).

Source: artofericwayne.com

During WW2, Kubin found himself on the wrong side of the Nazis with his artwork determined by them to be ‘entarte kunst’ (English ‘degenerate art’). Nonetheless, he managed to avoid being persecuted and he continued to work. He died in 1959.

The Illustration

Just one of numerous illustrations he did around this time, ‘Der Staat’ was produced using a combination of ink and watercolor on paper measuring 28.5 cm x 37.3 cm. The original is currently housed at the Museum of Modern Art (M.O.M.A.) in New York. Drawn in 1901, this was an early work by Kubin who did not even have his first exhibition until 1902 in Berlin.

Source: MoMA

Where Kubin may have got his inspiration for this fantasy is unclear, and it could easily be decided that as a work of art it could be discarded as unimportant in the history of the development of armored vehicles. Certainly, the design as shown has some serious deficiencies, and without delving into art-criticism the image is essentially an allegory of government.

What Kubin shows, however, in an age when the concept of a self-propelled armored war machine was still very much a novelty, is an interesting insight into an amateur’s idea of what such a machine might look like.

The Machine

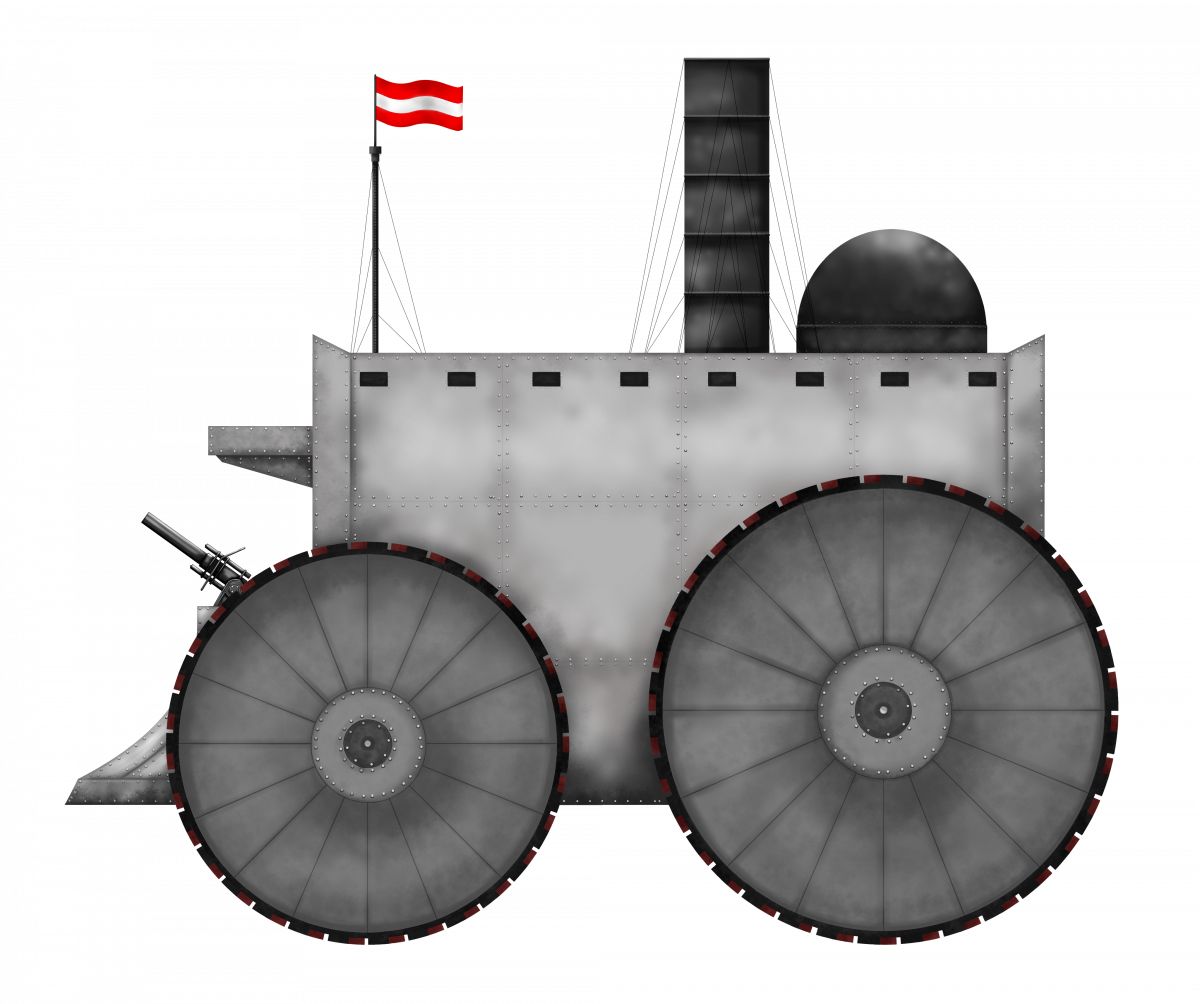

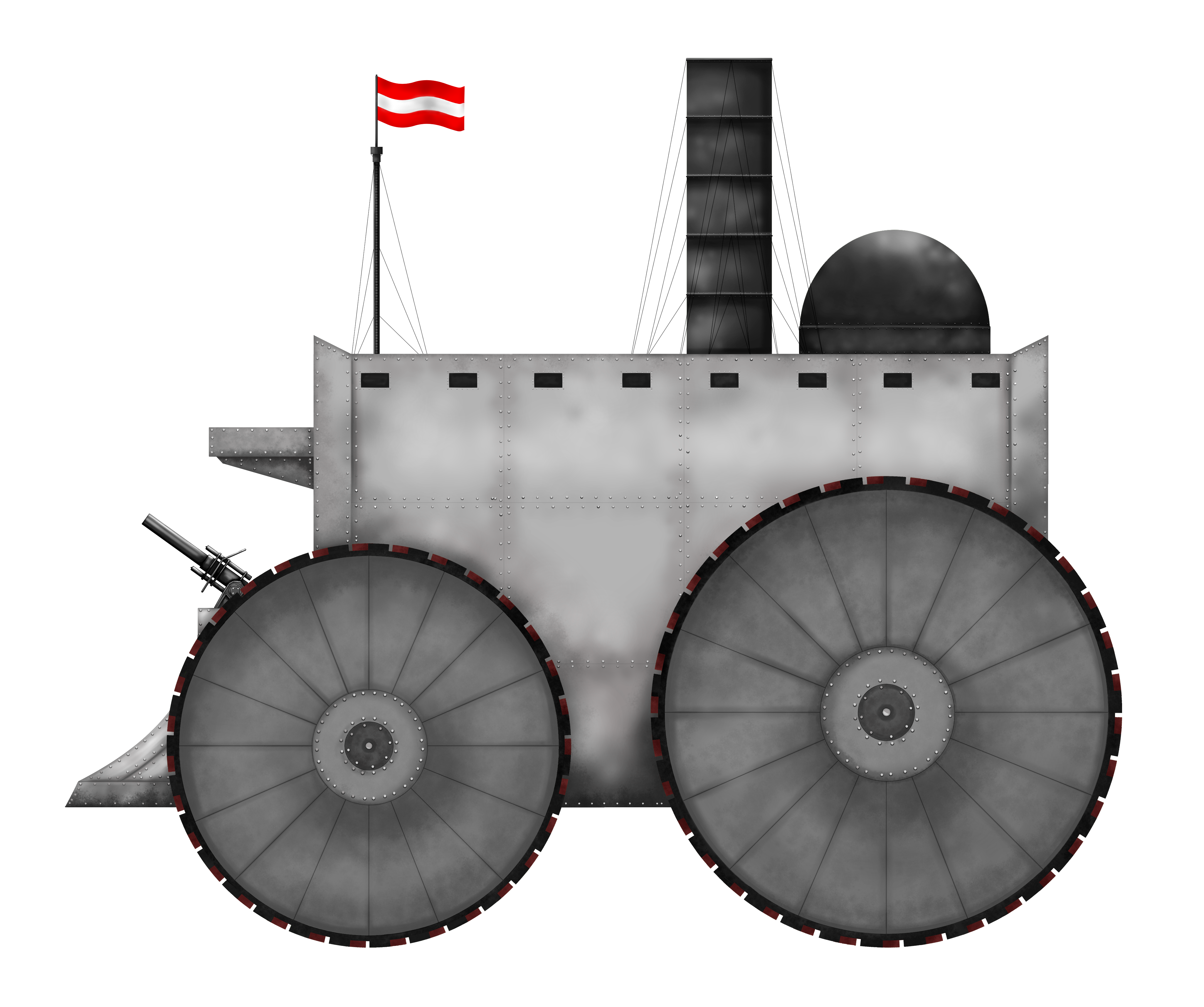

The basic shape of Kubin’s machine was a giant box. Four gigantic wheels dominated the sides of the box with the front pair smaller than the rear pair, and all four being of a substantial diameter. These wheels, without any apparent ability to steer them, are attached to the sides of a large metal body.

The front of this body is dominated by a naval-style prow. On top of this prow is a single cannon manned by what appears to be a 15th Century Spanish Conquistador. Above him, on the vehicle’s front, is a semi-circular balcony with a staircase leading from it to the flat roof of the machine. Numerous figures can be seen milling about on the roof putting into scale the enormous size of such a machine, although the drawing is clearly not to scale.

In the center of the roof are a pair of projections with one large domed structure of unknown purpose, and the second being a huge smoke stack belching an enormous cloud of black smoke behind the machine.

Small rectangular windows can be seen on the front and side of the hull along with rectangular panels bolted together. A flagpole sits atop the hull on the front right corner but the only obvious armament is that odd cannon on the balcony at the front over the prow.

As an allegory for the state, the machine is a large, simple and warlike one, but as a real weapon of war, it would be very poor indeed. Assuming steam power would have been the power plant of choice, then there is no logical reason such a machine could not be built and made to move if there was a bottomless budget to draw from and some kind of need to make the machine necessary.

Even without the scale being accurate, the size was massive. If the dimensions were based on that Conquistador at the front, the vehicle would still be in the region of 8 – 10 meters high. If instead it was scaled off the stick figures on the roof, then perhaps 100 m. At a minimum, the weight of such a vehicle would be in the hundreds of tonnes, perhaps thousands of tonnes. As a viable machine, it would have already been burdened by both its size and weight. These two factors would severely hamper its ability to move from one place to another, whilst providing an almost unmissable target.

Something weighing in the thousands of tonnes and yet born on just 4 wheels, albeit very wide ones, would also produce a lot of ground pressure and a great deal of sinkage. Perhaps the biggest flaw of the vehicle is the armament. A single gun on the front with at best 180º of coverage from the front would have left this massive target vulnerable to enemy artillery.

Conclusion

Kubin did produce some other military themed drawings, such as ‘War’ (1901-3) and ‘Army’ (1903). However, this vehicle, the state and war combined in one, is perhaps the most interesting from the perspective of what it preceded.

As a design, the vehicle is severely lacking. As art it maybe has more value. As an artifact showing the necessary elements for mobile armored warfare, it may provide yet more value. Kubin’s military career was brief at best, so it is not possible to infer any great military knowledge applied to the design. In 1901 he would also have had no real frame of reference for his design either, so some of the failings may be forgiven from a technical perspective.

Perhaps though, that is the point. Maybe Kubin was trying to convey the pointlessness of such a vehicle or parody the ridiculousness of it all. Art critique may provide the answers as to why, but what matters in terms of tanks is a different question.

What Kubin produced does not need to be a practical or even a viable armored vehicle in any sense. What it was, was an alternative vision of an armored machine, maybe purposeless, and maybe useless, but one predating the origins of tanks in 1915 and even before his more famous Austrian forebear, Günther Burstyn.

Sources

Mitchell, J. (1969). Alfred Kubin. Art Journal, Vol. 28 No. 4 (Summer 1969).

Gallery Henze , Ketterer, & Triebold, Bern. http://www.artnet.fr/galeries/henze-ketterer-triebold/traumgestalten-und-nachtmahre-/

Museum of Modern Art https://www.moma.org/collection/works/33912

History of Art http://www.all-art.org/symbolism/kubin1.html

Art Encyclopedia http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/kubin_alfred.html

Art of Eric Wayne.com https://artofericwayne.com/2018/01/29/eerie-alfred-kubin-forgotten-pioneer-of-symbolism-expressionism-and-surrealism/