Austro-Hungarian Empire/United States of America (1916-1918)

Austro-Hungarian Empire/United States of America (1916-1918)

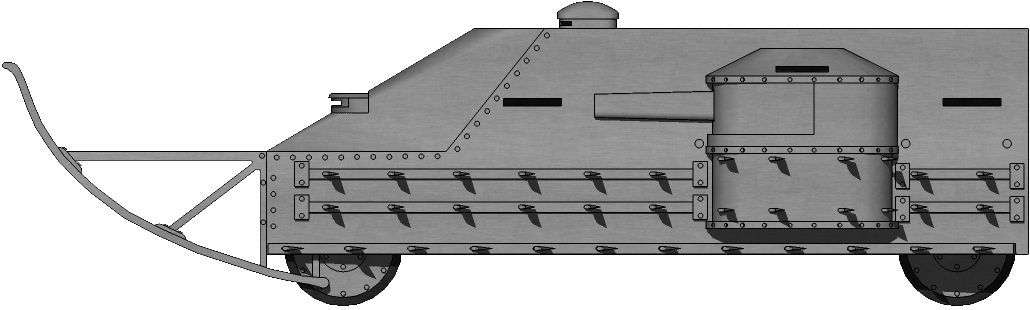

Armored Car – Blueprints Only

World War One had started much along the lines of previous wars. Political saber-rattling, followed by posturing, declaration of war and mobilization. Despite the growth in industrial potential across Europe at the turn of the century and the perfection of the machine gun as a practical weapon of war, the armies of Europe in 1914 went to war in much the same way as they had done in the previous century and yet were quickly faced with a new reality. Their men were easy prey to the rapid-firing effects of the machine guns.

There had been numerous ideas before the war for armored machines, but there was little impetus to develop one until the slaughter of WW1. That fate had befallen an Austrian called Gunther Burstyn, who had patented a very crude form of armored vehicle before the war but had done little with it. Another Austrian, Karl Kempny, far less well known or remembered, was living in Cleveland, Ohio, USA during the war. Kempny was not the visionary that Burstyn was, but was certainly quick to see the potential of armor. In 1916, he submitted his own ideas for an armored vehicle carrying heavy armament but still mounted on wheels. Future armored power was going to be best deployed on tracks, not wheels as envisaged by Kempny.

Divided Loyalties?

Little is known of Karl Kempny and any attempt to research the man online is sadly frustrated by a hockey player of the same last name playing for Cleveland. What is known of him, therefore, comes only from his patent applications. His name was given as Karl Kempny and he described himself as a subject of the Emperor of Austria, albeit living in Cleveland, Ohio, USA at the time. Whilst WW1 had started in the summer of 1914, and Austria-Hungary had been involved in military action right from the start, it was not until 1917 that the United States had come into the war. It was not, in fact, until 7th December 1917 that the US actually declared war against Austria-Hungary, even though it had already done so against Germany that April. At the time that the patents were submitted, therefore, between 20th November 1916 and 1st February 1917, there was no state of war between the USA and Austria-Hungary for Kempny to worry about. What is more interesting though is that this Austrian citizen was granted two patents for military designs in 1918 (including this armored automobile) at a time when the US was at war with his home country. To whom was the design intended then? Was Kempny, filing in 1916, suggesting his design was for use by Austria? If so, then he did not file an application for it there. It seems more likely that Kempny, a first-generation immigrant from Austria, not yet naturalized as a US citizen, filed his patent in his new adopted country for use either by them or for commercial purposes. Whilst Austria might have a claim on Kempny via ancestry, it would appear his vehicle is more appropriately assigned as an American one.

The Patents

As alluded to in the preceding paragraph, there was more than one patent. In fact, Kempny submitted three patents, two in 1916, and one in 1917, all for military equipment. The first, titled ‘moveable shield’, was one of dozens of wheeled, armored shields being suggested by a myriad of inventors, commentators, and military men throughout the First World War. Almost without fail, the designs were crude, clumsy and found no use. A man-propelled shield which was thick enough to be bulletproof was simply too cumbersome and heavy for even a small number of men to move. And that is before consideration is given to moving it over the tortuously muddy conditions of the battlefields of WW1 on the Western Front or the often vertigo-inducing mountainous terrain of the Southern (Italian) Front. Despite its flawed utility, his shield was nonetheless granted a patent in July 1917.

During the war, he filed his application for his armored automobile that December, followed three months later in February 1917 with a design for a bulletproof helmet. The helmet is certainly a novel design and one really has to wonder if Kempny was even serious with it given the design. Ludicrously tall and covered with spikes, the helmet consisted of a protective dome over the top of the head over which a taller helmet was fastened by means of springs. As if that was not impractical enough, the outside of this design was then clad all round the outer surface with spikes. All of that weight, precariously perched on top of the wearer’s head, was secured by just a single thin chin strap, meaning that as soon as the wearer might run or duck for cover, this spiked affair on top of his head would simply fall off and either impale him, another nearby soldier, or just get stuck in something. Truly, there can not be any helmet design which was less practical or realistic and perhaps that is why Kempny stopped submitting patents. He was just wasting his money on pure fantasy silliness.

The design between the shield and the helmet though certainly has some elements of fantastic and impractical thinking, but also of some common sense and is worthy of some consideration.

Armored Automobile

Filed in December 1916, the design was not approved until October 1918, just before the end of hostilities. His design was specifically intended as a vehicle for repelling attacks by enemy infantry but also for mounting rapid-fire guns in bullet-proof mounts. The overall layout is clearly that of a standard truck with an engine at the front, directly over the front axle, mounting a pair of steered-wheels. A further axle at the back was also fitted with a pair of wheels.

The body of the vehicle was essentially a large rectangular prism, flat vertical sides and rear and a flat horizontal roof. The front though was different. A large rounded section angled steeply backwards, going from above the engine to the roofline with a large horizontal viewing cupola halfway up. This cupola was for the driver to see out of and appears to have been located centrally behind the engine. A second cupola, fully rotatable, was mounted behind the point where the angled front met the roof and would provide the vehicle commander with all-round vision. Located centrally and at the front, the driver should have had good visibility of the ground in front of the vehicle, but he would have been unable as Kempny drew on a large curved shield extending from the front of the vehicle and up to a level above that of his cupola. Thus, the driver’s view ahead would be severely limited. The purpose of that large curved section at the front was to primarily force down barbed down as the vehicle approached but it also served as armor for the front of the vehicle, deflecting bullets away from the men inside.

Access to the vehicle was to be via a single large rear hatch with vision provided by the cupolas and by various vision slots in the side of the hull and in the sponsons.

No mention is made of armor except it would presumably have been armored to at least the level of being reasonably well protected against a service rifle. This would mean protection in the region of 8 mm or so of steel. As far as crew goes, there would need to be at least 4 men inside, a driver, a commander, and one man per gun. There is a lot of space inside the body and one use Kempny envisaged involved the removal of weapons and use as simply an armored lorry. This would suggest enough space for half-a-dozen or so more men even when armed.

Armament

The first and most obvious weapon on the vehicle are the spikes. These are actually sword bayonets mounted in rows along the side of triangular extensions attached to the side of the vehicle with the intention of making it harder to approach/climb when stationary and also to scythe through enemy troops when mobile. Thankfully, Kempny decided that these bayonets should be able to be folded away when not in use, or else the number of enemies they would be killing would surely only have been outweighed by the numbers of its own men, passers-by, and animals which would have been cut limb from limb as it went by. Despite the appearance of having a large cannon in each of the sponsons sticking out of the side, the Kempny design was to rely instead upon a pair of ‘rapid fire guns’ which could be machine guns or a cannon of some description with one in each sponson. Each gun was mounted on a rotating pedestal providing fire to the front, sides, and even to the rear. This type of mounting in an armored car, a sponson projecting from the side, was most likely the result of seeing exactly the same manner of armament carried on the first British tanks which were receiving a lot of press coverage at the time. As these were projecting from the side, it would mean the vehicle would be able to deliver fire straight ahead as well as to the sides. It would also affect lateral stability, as significant weight would be placed outside the wheelbase.

A Lithuanian Connection?

One small added mystery to the identity of Karl Kempner comes from the signatories to his armored automobile patent, acting as witnesses: Stanley Stanslewicz, and A.B. Bartoszewicz. Bartozewicz was also a witness on his shield patent and appears to be Apdonas B. Bartoszewicz (also known as Apdonas B. Bartusevicius) who ran a Lithuanian-language publishing company in Cleveland which included the printing of the newspaper Santaika (Peace) in 1915 and which changed name to Dirva (Field) in 1916. The fact that Bartozewicz witnessed two of Kempny’s designs suggests that they knew each other reasonably well, although the nature of the relationship is unclear. Perhaps they were related or business partners, or that Bartozewicz was a notable person locally, we may simply never know. Nothing today remains of Kempny’s legacy and even Bartoszewicz is almost forgotten. Only his name remains on a building in Cleveland.

Conclusion

Kempny’s shield added nothing new to the multitude of such designs and met with much the same fate. His helmet is memorable because it is simply such a totally impractical concept. His armored car however, is a different story. It was never built, never saw combat, and made no effect on the pursuit of the war so could easily be dismissed, but this would be wrong. His vehicle’s design clearly shows a popular mindset amongst designers at the time and just how little was understood about the true conditions at the front. Designs which could only operate on good surfaces and not the mud of Flanders are common, a complete misunderstanding of the conditions despite plenty of photographs available.

Yet, despite that misunderstanding, Kempny did foresee a multi-purpose vehicle, one suitable for carrying men and goods as much as for combat, a vehicle with weapons mounted in sponsons projecting from the side in the same manner as was used on tanks and an appreciation of the problems of barbed wire.

Kempny wanted to simply crush it down and roll over it, things which were tried and failed. The influence of the British tanks of 1916 can even be seen in the design, yet overall the design was still a retrograde one.

It is not known who, if anyone, may have seen Kempny’s design at the time and it is unlikely that it had any influence on following designs, especially the wholly impractical idea of the sword bayonets on the side, but Kempny’s design illustrates the time well – a no doubt well-meaning amateur designer, a first generation immigrant to the US trying to have his voice heard during the maelstrom of war. Whilst his design for an armored automobile went nowhere, received no orders, and was never built, Kempny’s armored automobile provides an insight into how the war was still being seen on the home front at the time.

Illustration of Kempny’s Armored Automobile produced by Mr. C. Ryan, funded by our Patreon Campaign.

Specifications |

|

| Crew | est. est. 4 driver, commander, 2 x gunners) + ~ 6 men |

| Armament | multiple rows of sword bayonets, 2 x rapid-fire guns |

| Armor | Bulletproof |

| Engine | a ‘suitable motor’ |

Sources

US Patent 1234174 ‘Moveable Shield’, filed 20th November 1916, granted 24th July 1917

US Patent 1251537 ‘Bullet Proof Helmet’, filed 1st February 1917, granted 1st July 1918

US Patent 1282235 ‘Armored Automobile’, filed 18th December 1916, granted 22nd October 1918

‘Dirva’, Ohio History Central

One reply on “Kempny’s Armored Automobile”

Please estimate the speed.