Italian Republic (1945-Early 1950s)

Italian Republic (1945-Early 1950s)

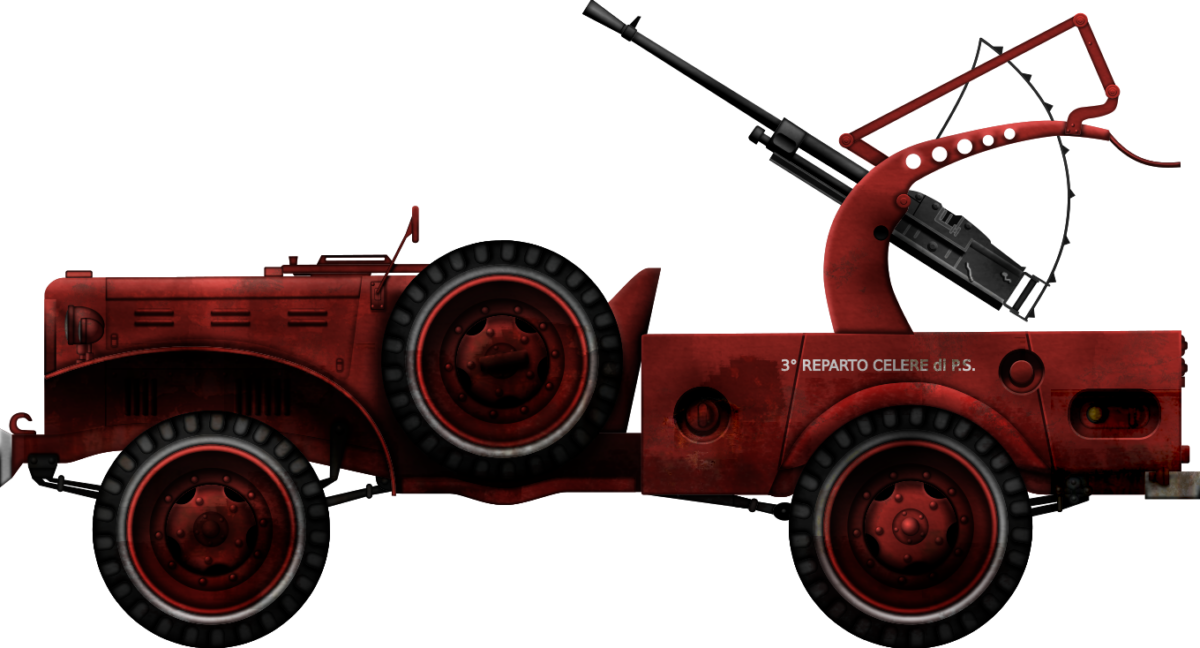

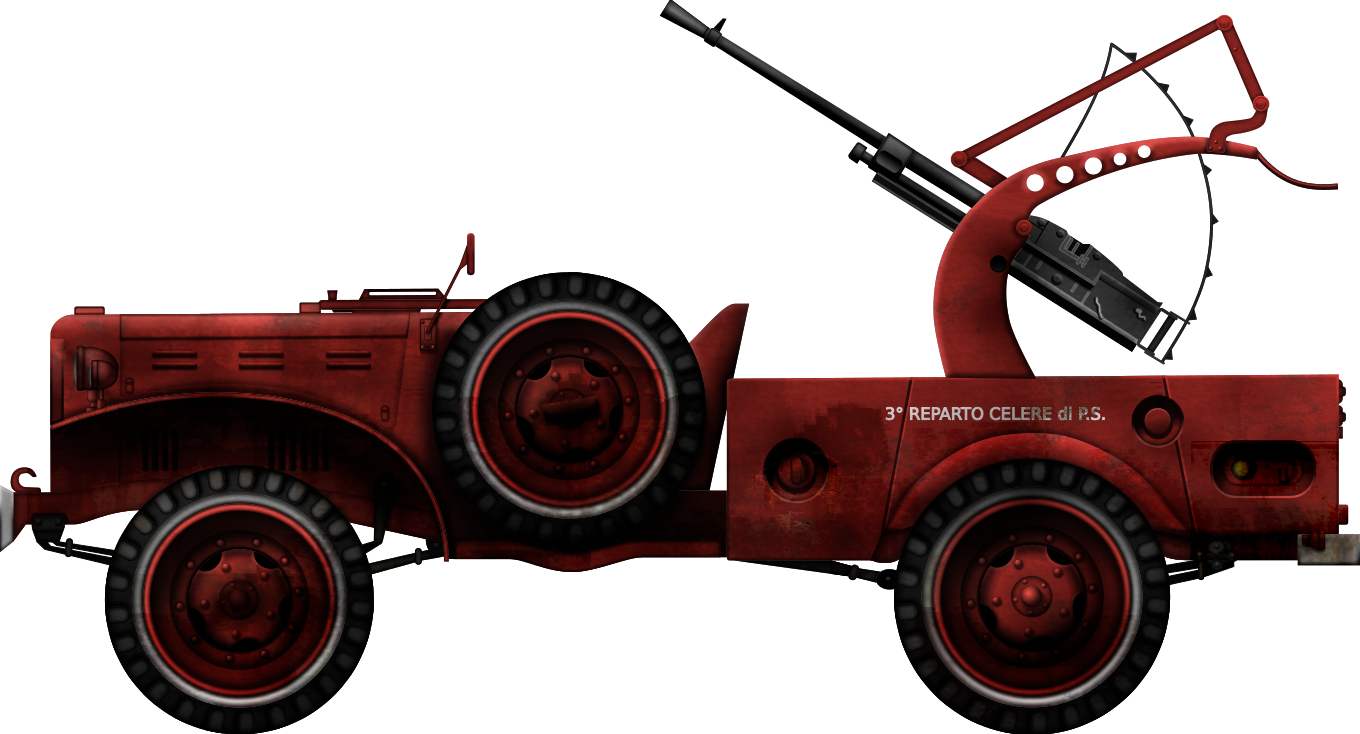

Truck-Mounted Artillery – Unknown Number Modified

The Autocannone da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51 was the last truck-mounted self-propelled gun modified by the Italians after the Second World War. A few were produced and used by the Corpo degli Agenti di Pubblica Sicurezza (English: Corps of Public Safety Officers), which was renamed Polizia di Stato (English: State Police) after 1947. It was used as a public order vehicle in urban operations.

It is perhaps one of the least famous Italian-produced autocannoni, probably in large part because it entered service after the war and its service is poorly documented. In Italian, ‘Autocannone da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51’ means Truck-mounted 20 mm L.65 on Dodge WC-51 [chassis].

Context

The Corpo degli Agenti di Pubblica Sicurezza (English: Public Safety Agents Corps) was the main Italian police corps, alongside the Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali (English: Royal Carabinieri Corps), between 1851 and December 1922. When Benito Mussolini came to power and disbanded the corps (most police officers joined the Carabinieri), substituting them with Fascist militias.

There were a total of 16 Fascist militias, such as the Milizia Confinaria (English: Border Militia) with border police duties, Milizia Artiglieria Contraerea (English: Anti-Aircraft Artillery Militia) with the task of defending Italian airspace, Milizia ferroviaria (English: Railway Militia) with the task of supervising railways, Milizia portuaria (English: Harbor Militia) tasked with the supervision of the ports and maritime domains, Milizia della Strada (English: Street Militia) in charge of traffic, etcetera.

Another important corps was the Polizia dell’Africa Italiana or PAI (English: Police of Italian Africa), which was in effect a military corps. It was created in 1936 and was under the direct command of the Italian Ministry of the Colonies.

On 10th June 1940, the Kingdom of Italy entered the Second World War alongside the Axis powers. After a series of defeats, on 25th July 1943, the Italian king, Vittorio Emanuele III, had Mussolini arrested, but maintained an alliance with Nazi Germany.

In August, the new Italian head of government, Marshal of Italy Pietro Badoglio, began negotiations for an armistice with the Allies. This was signed by his delegate on 3rd September 1943 and made public only on 8th September 1943 at 19:42 (Rome time zone).

The German reaction was immediate. The same day, they initiated Fall Achse (English: Operation Axis), which led to the complete occupation over a few days of the Italian territory not yet occupied by the Allies. This was accompanied by the killing of 20,000 Italian soldiers and the capture of over a million other Italian soldiers, as well as a war booty of almost 1,000 armored vehicles and tens of thousands of artillery pieces and other materiel.

The head of government, Pietro Badoglio, along with King Vittorio Emanuele III, their families, and some politicians and generals, reached the allied positions in Brindisi, southern Italy, during the early morning of 9th September. In early 1944, a new government was created in Salerno and was composed of a total of six anti-fascist political parties.

During this period, in the territories freed by the Allied forces, the Italian Government needed to govern and maintain public order. With the legislative decree n. 365 of 2nd November 1944, issued during the lieutenancy of Umberto II di Savoia (son of the king who, in the meantime, had retired to private life), the ‘Corpo delle Guardie di Pubblica Sicurezza’ was established again with the status of a military corps.

The Polizia dell’Africa Italiana was disbanded when Rome was liberated by US soldiers in early June 1944. Its police officers, guns, and vehicles were delivered to the Corpo delle Guardie di Pubblica Sicurezza in November, together with staff cars, trucks, and motorcycles of different origins. These were Italian civil and military ones, some captured from the Germans or vehicles donated by the Allied powers.

After the war, the inevitable judgment fell on the Kingdom of Italy. It had to abandon its colonies and cede territory to France and Yugoslavia. According to the clauses of the Treaty of Paris, the army could have a maximum of 185,000 soldiers, 200 tanks, and could not have long-range artillery pieces.

Because of the constant risk of a pro-Communist coup d’état, especially in the period of 1945 to 1950, the British and US authorities allowed Italy a significant margin to maneuver. In fact, the Corpo delle Guardie di Pubblica Sicurezza and the Copro del Carabinieri Reali were not affected by the organizational or equipment restrictions.

Furthermore, shortly after the end of the Second World War, Italy and Communist Yugoslavia clashed over the sovereignty of territories on the border between the two countries. The British and US leniency allowed the Italian Government to equip its public duty corps as a military corps with heavy armored cars, automatic cannons, mortars, and even light and medium tanks.

The fears of the Allies were not unfounded. The Italians were not confident in the initial temporary government. Many were in favor of the monarchy, some wanted to become a Soviet-backed nation, while others, after years of oppression from the Fascist government, no longer trusted the institutions.

After 5 years of war, 2 of which were on Italian territory, it was easy to find weapons and explosives on the black market. This allowed organized crime to be well equipped. Also, during demonstrations, protesters often took guns with them for self-defense, as Italian police, during the first years of the Italian Republic, clashed with demonstrators with violence, often shooting at them.

In southern Italy, banditry, for many a problem from the past, returned, especially in Sicily, where, in 5 years, 21 policemen and 12 other soldiers and Carabinieri lost their lives. Between 1948 and 1960, a total of 90 protesters and 6 policemen were also killed during strikes. In addition to these internal problems, the eastern border with Yugoslavia was threatened with attacks by independent units of Yugoslav criminals.

After the end of the war, members of the 16 Fascist militias, now dissolved, flocked to the new policed corps. They were joined by personnel from the former PAI, former Polizia Ausiliaria Partigiana (English: Partisan Auxiliary Police), the dissolved Polizia Repubblicana, and members of the Italian Co-Belligerent Army, all with a military education. Former members of Fascist units formed after the signing of the Armistice and particularly faithful to Mussolini and his ideologies, such as the Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana (English: Republican National Guard), the Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano (English: Republican National Army), and the Black Brigades were forbidden from joining the new police force.

In 1946, the secessionist movement in Trentino Alto Adige (a region in the northeast of Italy) wanted to join Austria. The social and political tension in the region was very high and clashes broke out, which resulted in several deaths and injuries. On 22nd August 1946, in Turin, former Partisans took up arms again and entrenched themselves outside the city and in some buildings, without shooting. In their opinion, the state was too forgiving of former soldiers and Fascist higher-ups who had committed war crimes.

Quickly, the revolt flared up throughout central and northern Italy and arrived in Rome, where clashes between police and Partisans resulted in gunfights with deaths and injuries. In October 1946, in the industrial cities of northern Italy, violent clashes broke out in the streets, with protesters demanding higher wages and better working conditions.

In 1945, the Polizia Stradale (English: Street Police) was formed to ensure compliance with traffic regulations and the Polizia Ferroviaria (English: Railway Police) to enforce public order across the rail network.

In 1946 and 1947, the Reparti Celeri (English: Fast Departments) of the police were formed. There were the I° Reparto Celere (English: 1st Fast Department) in Rome, II° Reparto Celere (English: 2nd Fast Department) in Padova, and III° Reparto Celere (English: 3rd Fast Department) in Milan. In Italy, these units are, to this day, depending on the context, but often derogatorily, called ‘Celerini’.

These units had the task of intervening quickly where there was a need for public order, for help after natural disasters, or in case of a clash with a foreign army or organized guerrilla. For this reason, they were positioned at strategic points of the Italian peninsula. The one in Padova was near the border with Yugoslavia, the one in Milan was in the center of northern Italy and could intervene in a few hours throughout the north and north-west, and the one in Rome was used to intervene near Rome, but also as a defense unit in case of an attack or coup d’état in the capital of Italy.

During the following years, other Reparti Celeri were created in Turin, Bologna, Genoa, Florence, Naples, Reggio Calabria, Bari, Palermo, Catania, and Cagliari, in order to allow quick intervention across the Italian peninsula. Within the Mobile Departments, in 1949, the Reparto Speciale Paracadutisti della Polizia di Stato (English: Special Parachute Department of the State Police) was created and stationed in Cesena.

It was composed of volunteer police officers and former members of the dissolved 185ª Divisione paracadutisti ‘Folgore’ and 184ª Divisione paracadutisti ‘Nembo’ (English: 185th and 184th Parachute Divisions). The unit was created to quickly deal time with serious and unexpected disturbances of public order.

On 2nd June 1947, the Italians went to the polling stations to vote in a referendum on whether to remain a monarchy or become a republic. Although not with an overwhelming majority, the republic option won and the Kingdom of Italy became the Repubblica Italiana (English: Italian Republic). During the same period, the names of the police corps were changed. The Corpo delle Guardie di Pubblica Sicurezza became the Polizia di Stato (English: State Police) and the Corpo del Carabinieri Reali became the Arma dei Carabinieri (English: Arm of Carabinieri).

In 1948, the Reparti Mobili (English: Mobile Departments) of the police were created. These units were quite similar to the Reparti Celeri, with the only difference being that they were less well equipped.

There were a total of twenty Reparti Mobili stationed in the bigger cities of Italy and where the possibility of a revolution was larger, such as the I° Reparto Mobile in Turin and the XX° Reparto Mobile in Cesena. These units were rarely used by the Italian governments until the mid-to-late 1950s when the fear of coups had diminished and the army was finally becoming well equipped.

Each Reparto Mobile consisted of a command and service company, an 81 mm mortar platoon, a transport platoon, and two mobile companies with a command platoon, a machine gun squad, and three mobile platoons with 3 rifle squads each. Finally, there was an armored company with a command squad, a motorcycle platoon, and two armored car platoons.

In total, each unit was composed of 17 officers, 57 non-commissioned officers, 406 policemen, 12 armored cars, and an unknown number of other vehicles. Some departments were then divided into nuclei (the equivalent of platoons) and sottonuclei (equivalent to squads) or detached companies, which were often deployed to other cities close to the headquarters in order to speed up interventions.

These units still exist in Italy, even if their employment is limited and their staff has drastically changed. By the late 1950s, the Polizia di Stato returned to being a simple police and public security corps. Today, there are 15 Reparti Mobili, with a total 4,633 police officers, that usually intervene with public order duties during student or worker strikes. Their usual equipment does not go further than a police IVECO Daily truck with protected windscreens and headlights.

Design

Truck, Cargo, 3⁄4-ton, 4×4, Weapons Carrier WC-51

The Truck, Cargo, 3⁄4-ton, 4×4, Weapons Carrier WC-51 was a light military utility truck developed by Dodge in late 1941 from previous ½-ton trucks. The acronym WC does not stand for ‘Weapons Carrier’, but was a general Dodge model code: ‘W’ for 1941, and ‘C’ for a half-ton payload rating. Even if this code was initially used for the ½-ton trucks from which the vehicle was derived, the code was kept for the more powerful WC-51 and WC-52.

The WC-51 and WC-52 differed. The Dodge WC-52 had the powerful Braden MU-2 winch driven by the Power Take-Off (PTO) and a towing payload of 3,400 kg, mounted on the front bumper. To accommodate it, the WC-52 was built on a 20 cm longer chassis than previous models.

In total, 123,541 trucks were built without a winch as WC-51s and 59,114 with a front winch as WC-52s, a total of 182,655 weapon carriers, troop transports, or cargo vehicles. The total production run of these vehicles was 255,195 units when also considering ambulances, Gun Motor Carriages, and other variants.

During the Second World War, the Dodge WC-51 and WC-52 were provided under the Lend-Lease Act to other Allied powers. The Soviet Union received 24,902, 10,884 to Britain, 3,711 to China, 3,495 to the Free French forces, and about 1,200 to Brazil and other Latin American countries.

The WC-51 was a total redesign from the earlier 1⁄2-ton models, but it shared many components with these. The main differences were the jeep-shaped bodywork, a 1.64 m track width compared to 1.56 m of the 1⁄2-ton models, and a shorter 2.49 m wheelbase instead of the 2.95 meters of the earlier models. The tires were also changed. The previous 7.50 × 16” (19 x 60.5 cm) were substituted with the bigger 9 x 16” (22.8 x 60.5 cm), giving better off-road capabilities to the new 3⁄4-ton trucks.

The Dodge WC-51 had left-hand drive, with 2 seats in the open-topped cab without doors. The driver’s seat was on the left. The spare wheel was also placed on the left. The windshield could be lowered to the front, on the engine hood, allowing the vehicles equipped with guns to have a full 360° of traverse.

The cargo bay had two lateral benches where eight fully equipped soldiers could be seated. Alternatively, 800 kg of cargo could be loaded. An M24A1 gun mount was optionally mounted on the cargo bay to arm the vehicle with a 7.62 mm or 12.7 mm Browning machine gun or 57 mm M18 recoilless guns. After the Second World War, it was used during the Korean War or was donated to many allied United States nations.

In Italy, after the war, the Azienda Recupero Alienazione Residuati or ARAR (English: Company of Recovery and Alienation Survey) society was entrusted with the task of reconditioning and selling military vehicles confiscated from the enemy or abandoned by the Allied armies on Italian territory by the Italian Government of National Unity after the Second World War.

The police had the possibility of buying hundreds of those vehicles after 1945, mainly Willys MB jeeps and Dodge ¾-ton trucks. Many other vehicles were also acquired, such as US GMC 353 and Dodge T-110 trucks, German Opel Blitz, British CMPs, and the ubiquitous FIAT and Lancia trucks. Some of these vehicles were also delivered to the Polizia di Stato by the Allied armies in 1945 when they left Italian territory, since it was costly to repatriate them.

Between 1945 and the early 1950s, Willys MBs were the most used vehicles by the Italian police force. These were fast and always ready to transport a small police unit anywhere. In case of major law and order problems, the Dodge WC-51s and WC-52s, which could carry up to 10 police officers on board or some detainees, were also used.

The Dodge ¾-ton trucks were nicknamed ‘Jipponi’ (English: Big Jeep) by the Italian units, since the bodywork was similar to that of the Willys Jeeps, even if they were light trucks.

The police units used the ¾-ton trucks produced by Dodge mainly as ready-to-use police cars, but also in other roles. Today, all police cars are equipped with radios to contact the police station at any time. In the 1940s and 1950s, radios were too large and heavy to be carried by all vehicles, and some Dodges were transformed into radio centers. Radio equipment was mounted on the loading bay, just behind the cabin, as were a radio transceiver station of Italian or American production and an antenna to stay in touch with the police station.

These vehicles were rarely used, mostly during demonstrations or natural disasters, in order to request reinforcements or make reports. Most of the WC-52 models were assigned to disaster relief units because of their powerful winches. Others were employed as armed trucks, mounting 8 mm Breda Modello 1937 or Modello 1938 machine guns on a pintle mount or 20 mm automatic cannons.

Engine and Suspension

The vehicle was powered by a Chrysler T-214 L-head, 6-cylinder, in-line petrol 3,772 cm³ engine delivering a gross power of 92 hp and a net power of 76 hp at 3,200 rpm. The carburetor was a Zenith Model 1929.

It offered a maximum speed of 85 km/h. The 135-liter tank offered an on-road range of 440 km, with a fuel consumption of 1 liter every 2.25 km.

The manual gearbox had sliding gears, with 4 forward and one reverse gears. It had a single dry disc clutch with hydraulic drum brakes. The suspensions consisted of leaf springs on the front and rear axles. The front leaf spring suspensions were coupled to Monroe telescopic shock absorbers. The 6 Volt electric system was connected to the front and rear headlights, dashboard and horn.

Main Armament

The autocannone’s main gun was the Cannone-Mitragliera Breda da 20/65, mainly the Modello 1939 version, but at least six vehicles in service in Padova were also equipped with the Modello 1935 version.

The Breda gun was a gas-operated automatic cannon chambered for the powerful 20 x 138 mm B cartridge, the same as used by the German FlaK 30 and FlaK 38 AA guns, the Swiss Solothurn S-18/1000 anti-tank rifle and the Finnish Lahti L-39.

Its theoretical rate of fire was 500 rounds per minute, but the practical one was about 220 rounds per minute due to the 12-round feed strips that were loaded manually.

It had a muzzle velocity of 830 m/s with anti-aircraft rounds and a bit faster for the armor-piercing rounds. Its maximum firing range was 5,500 m, while the practical range was 2,000 m in the anti-aircraft role and about 3,000 m against ground targets.

The Modello 35 mounting had a -10° depression and +80° elevation, while the Modello 1939 had a depression of -10° and an elevation of +90° thanks to its manual aim. The gun used 12-round feed strips loaded from the left side. This made the loading slower, because it was not equipped with large-capacity magazines like the 60-round drum magazine of the Oerlikon 20 mm autocannon or the 20-round box magazines of the German 2 cm FlaK guns. The loader had to manually load each strip.

The Modello 1939 was the fixed gun version produced during the Fascist regime, made mainly for the Milizia della Difesa Territoriale (English: Militia for Territorial Defense), the equivalent of the British Home Guard during the Second World War.

The 72 kg heavy automatic cannon was mounted on a particularly shaped trunnion that offered 360° traverse and simplified the use of the gun. The guns used by the III° Reparto Celere in Milan were probably taken from the Arsenale di Torino (English: Turin Arsenal), which had overhauled and returned to service hundreds of armored vehicles, artillery pieces, and machine guns after the war. The II° Reparto Celere in Padova probably took these from the MLI Battaglione Carristi Autieri (English: 1051st Tank Driver Regiment) in Padova, which overhauled hundreds of pieces of military equipment as well.

The Modello 1935 was the towed variant of the automatic cannon. It was lower than the Modello 1939 and equipped with a seat and aiming wheels. It was the most produced variant and was the most used by the Regio Esercito during the Second World War. It was also used on the cargo bay of medium trucks as an anti-aircraft portée, using chassis such as the FIAT 626NM and FIAT-SPA 38R. The latter was tested in 1938 the Autocannone da 20/65 su FIAT-SPA 38R that was never officially adopted by the Regio Esercito but was modified by the soldiers on the battlefields to defend themselves from enemy aircraft attacks.

One problem with the Italian autocannone was the removal of the water-proof tarpaulins that protected the cargo bay from rain. When not in use, the 20 mm Breda’s breech and barrel had to be covered by small waterproof tarpaulins.

The ammunition was transported in metal boxes placed in the cargo bay’s floor. It was common practice for crews to transport more ammunition within crates loaded in the cargo bay or wherever there was sufficient space. More ammunition was transported by supply vehicles and ammunition carriers, probably Utility Truck ¼ t 4×4 Willys MBs.

Ammunition

The gun fired the 20 x 138 mm B ‘Long Solothurn’ cartridges, the most common 20 mm round used on 20 mm guns of the Axis forces in Europe, such as the German FlaK 38, Finnish Lahti L-39 anti-tank rifle, and Italian automatic cannons.

It could fire various types of rounds, although it is not clear exactly which types of rounds were used by the Polizia di Stato. After the Second World War, lots of different stocks of ammunition were used by the Italian troops. Italian 20 mm shells produced before 1945, German-made 20 mm bullets captured or abandoned on Italian territory and returned to service with Italian units, or 20 mm ammunition produced in Italy after the war could all have been available.

| Cannone-Mitragliera Breda da 20/65 Modello 1935 ammunition | ||||

| Name | Type | Muzzle Velocity (m/s) | Projectile Mass (g) | Penetration at 500 meters against an RHA plate angled at 90° (mm) |

| Granata Modello 1935 | HEFI-T* | 830 | 140 | // |

| Granata Perforante Modello 1935 | API-T** | 832 | 140 | 27 |

| SprenggranatPatrone 39 | HEF-T*** | 995 | 132 | // |

| Panzergranatpatrone 40 | HVAPI-T**** | 1,050 | 100 | 26 |

| Panzerbrandgranatpatrone – Phosphor | API-T | 780 | 148 | // |

| Note | * High-Explosive Fragmentation Incendiary – Tracer ** Armor-Piercing Incendiary – Tracer *** High-Explosive Fragmentation – Tracer **** Hyper Velocity Armor-Piercing Incendiary – Tracer |

|||

Crew

The Autocannoni su Dodge had a crew of 4 or 5: commander, driver, gunner, and one or two loaders. The driver was on the left side of the vehicle. The vehicle’s commander, generally an officer, sat on the right side. The gunner and one or two loaders sat on the benches on the cargo bay’s sides. In some cases, these had foldable backrests.

The vehicles could also transport some police officers on the benches and employed to maintain public order and to protect the vehicle from strikers.

The crew members were all armed with pistols, but probably, in some cases, they could also transport carbines or submachine guns for self-defense, even if in photographic evidence, none of the crew members are armed with these types of guns.

Operational Use

On 27th November 1947, the Minister of the Interior, Mario Scelba, removed the Prefect of Milan, Ettore Troilo, a former Partisan with clear Socialist tendencies. This act unleashed protests through the entire city and the government was forced to deploy the police departments, which at the time were not well seen by the population due to their violent actions during demonstrations, even peaceful ones.

Minister Scelba was a promoter of a hard-line approach against leftists. After initially opening police ranks to former Partisans, Scelba changed plans. He tried to identify all those who, in his opinion, were dangerous Communists. He forced leftist former Partisans and left-leaning police officers to resign through continuous harassment and non-stop transfers from one city to another.

On this occasion, the Corpo delle Guardie di P.S. was deployed in Milan together with the Army. It deployed in force despite the climate of extreme tension that many journalists had defined as a “coup d’état clime”. Barbed wire was placed together with autocannoni and tanks in some streets to prevent attacks from the protesters.

Luckily not a single shot was fired and there were no injuries during the demonstrations, a very rare occurrence, as the workers’ demonstrations often ended with deaths and injuries. Thanks to the political intervention of Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi and Secretary of the Partito Comunista d’Italia or PCI (English: Communist Party of Italy) Palmiro Togliatti, the situation returned to normal within a few days.

Some Dodge WC-51’s armed with 20 mm automatic cannons were positioned to defend the police headquarters in Milan, together with Carri Armati L6/40s and a Carro Armato M13/40. Fortunately, they did not have to intervene.

On 14th July 1948, Palmiro Togliatti, General Secretary of the Italian Communist Party and former Deputy Prime Minister of Italy, was shot at by Antonio Pallante, a strongly anti-communist fascist student. A general strike broke out all over Italy. At first, the worst was feared, as Togliatti was seriously injured after being shot at three times. In some cities, during the protests, armed former Partisan and revolutionaries occupied factories and other industrial and political strongholds.

The Polizia di Stato was deployed in all the squares of the main cities of the peninsula. In order to avoid a bloodshed, the government kept the Army in its barracks, but was ready to intervene.

In Genoa, Livorno, Naples, Rome, Taranto, and in the cities of the north, violent gun fights broke out, which left 14 dead and 204 wounded, many of them police officers. In Genoa, on 15th July, the demonstrators got the better of the police officers, some of whom were disarmed and taken prisoner. The fiercest demonstrators created railway and telephone blockades that paralyzed the country. In Milan, in Piazza Duomo, the situation had become uncontrollable.

The Autocannoni da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51s were deployed in the square but, despite this, the demonstrators showed no fear and were ready for a battle. In the afternoon, however, news that cyclist Gino Bartali, much loved by Italians, had won the Tour de France, changed the fate of Milan. Incredibly, as some journalists described, the tense situation suddenly turned into joy and the demonstrators began to rejoice together with the police. Togliatti survived his wounds and remained active in politics until his death in 1964.

On 12th March 1949, the Reparti Celeri of the police were again deployed in Bologna, Milan and Rome to quell protests against the Italian government’s adhesion to the US sponsored Marshall Plan. Even during these events, the State Police proved to be up to the task and there was a limited number of injured. In Milan, the Dodges did not have to intervene ever again.

An issue that the previous Fascist government had ignored was the agricultural problem. Most of the cultivated land in Italy was in the hands of landowners who exploited the laborers, making them work hard and paying them very little. During the Fascist period, any kind of protest was forbidden and the few that took place in the countryside were viciously repressed, the instigators deported, and was never reported in the media.

After the war, however, the situation changed. The salaries of laborers decreased due to the post-war crisis. In 1946 and 1947, farm workers began large strikes in Emilia Romagna and throughout southern Italy, where most of the farmland was located.

In 1946, Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi proposed a law, the ‘Lodo De Gasperi’, which required large landowners to compensate the laborers for the damages suffered during the war and forced them to hire unemployed laborers. On 7th January 1948, however, a commission issued a ruling that granted the peasants of Friuli (a region of Italy) only one third of what was provided by the law at the national level.

This led to a popular uprising that, fortunately, did not claim any victims. After some demonstrations and rallies in the squares during the first days, some peasants attacked some of the landowners’s residences.

The police were immediately called to intervene and the Dodges WC-51s were deployed, fearing that the laborers could become violent or barricade themselves in the residences or in the farms with guns. It did not come to that. All the laborers were cleared out and, in the few residences they did manage to enter, only some food was stolen.

In 1950, the Italian Parliament passed Law no. 841 of 21st October, also known as the ‘Legge Stralcio’. It was financed with the money from the Marshall Plan. The law proposed, through expropriation, the distribution of land to farm workers, making them small entrepreneurs and no longer subject to the large landowners.

In the summer of 1953, the reparti celeri were deployed to the border with Yugoslavia, at the height of the political crisis over the city of Trieste. This location was under Anglo-American rule and claimed by both Italy and Yugoslavia. Milan’s and Padova’s Autocannoni da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51 were involved in these actions. On 5th November 1954, a detachment of the II° Reparto Celere of Padova was the first Italian unit to enter Trieste.

The exact number of Dodge WC-51 Autocannone built is impossible to determine, they could range from 6 vehicles (only 2 license plates are known) up to several dozens. From the black and white photos, it is possible to deduce that the few modified vehicles were painted in amaranth, a reddish-rose shade of red, with white bumpers and wheels, and the word ‘POL’ for Police on the rear left bumper.

The amaranth color was chosen after the war as the livery for all police vehicles. This decision was made for two reasons. First and foremost, at the time, there were no police sirens and a red vehicle was very visible on city streets. Second, this particular shade of red covered very well the military camouflage paints previously used on former military vehicles. Each police unit then used a specific shade of amaranth, as they were painted by private companies that were given the contract.

It is possible to speculate that the windshield support also had the marking ‘Reparto Celere’, as on other vehicles used by the celere departments.

Conclusion

The Autocannone da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51 was the last autocannone produced by the Italians, shortly after the war. It was produced in small numbers and used only by the Italian police which, due to the restrictions on the Italian Army of the Peace of Paris, was used as a paramilitary unit to maintain the peace and order in the Italian territory.

Information about these vehicles is scarce. They were only rarely photographed in moments of maximum tension between the Italian state and population in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

There is no police or army documentation on this vehicle and it is also rarely mentioned in the most authoritative military history books covering Italy. Because of its rarity, most Italian military history enthusiasts are unaware of its existence.

Autocannone da 20/65 su Dodge WC-51 specifications |

|

| Dimensions (L-W-H) | 4.24 x 2.11 x ~2.5 m |

| Total Weight, Battle Ready | 3 tonnes |

| Crew | 5 (driver, commander, gunner and 2 crew members) |

| Propulsion | T-214, 3,772 cm³, 76 hp at 3,200 rpm |

| Speed | Road Speed: 85 km/ Off-Road Speed: 50 km/h |

| Range | 440 km |

| Armament | Cannone-Mitragliera Breda 20/65 Modello 1935 or Modello 1939 |

| Armor | // |

| Production | unknown |

Sources

Gli Autoveicoli da Combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano Volume III, Tomi I and II – Nicola Pignato – Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito

https://polizianellastoria.wordpress.com/