Kingdom of the Netherlands/Royal Dutch Shell (1929)

Kingdom of the Netherlands/Royal Dutch Shell (1929)

Armored Car – 2 Built

In 1929, Venezuelan revolutionaries performed a successful surprise attack on a Dutch fortress on Curaçao in order to capture the fortress’ arsenal. The goal was to use these weapons to overthrow Caudillo Juan Vicente Gómez in Venezuela. The Dutch governor and the military commander of the island were both taken prisoner. During the chaos, the director of the oil refinery on the island ordered the construction of two armored cars which would be used to defend the refinery against a potential attack by the revolutionaries.

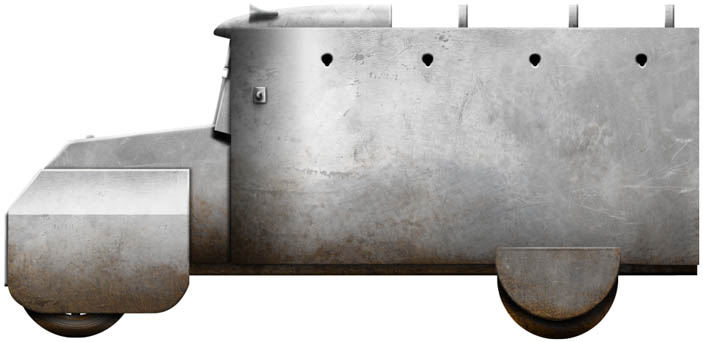

One of two armored cars, note the crude fitting of the metal sheets.

Short history of Curaçao

Curaçao is a 144 km2 island which is part of the Lesser Antilles and located above the coast of Venezuela. In 1499, the island was discovered by a Spanish expedition which enslaved most of the native Caquetio people, who were later sent to the island of Hispaniola. Together with the small neighboring islands of Aruba and Bonaire, Curaçao (the ABC islands) was considered ‘useless’ by the Spanish, as there were not many natural resources, such as gold deposits. Furthermore, the soil was not suited for agricultural exploitation, but cattle thrived on the island. In 1634, only around 30 Spaniards remained on the island, when it was successfully invaded by the Dutch West-Indische Compagnie (West India Company, WIC for short).

The island was quickly fortified to defend it against a potential Spanish attack.

The Spaniards indeed tried on one occasion to recapture the island, but due to the wind heading in the wrong direction, they could not land, and a renewed attempt was never made. As such, the island remained in Dutch possession. In the meantime, the population grew steadily, plantations were built, and the island became an important trading post due to its deep natural harbors and close proximity to the Venezuelan coast. Slave trade began in 1665 and, in 1674, Curaçao became a free-trade zone, increasing its position in the international trade network. However, during the 18th century, French and English colonial possessions in the Caribbean, became more and more powerful, decreasing Curaçao’s role in trade with revenue dropping and, in 1791, the WIC had to file for bankruptcy.

The island became an official Dutch colony and property of the Netherlands. In 1800, due to the French occupation of the Netherlands, Curaçao was invaded by the British. They were expelled from the island by the local inhabitants in 1803, but returned in 1807 and kept control of Curaçao until it was returned to the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1816. The economy mostly depended on trade (the slave trade was abolished in 1863), agriculture, and fishing. After 1816, the island was defended by a garrison of nearly 370 men with the primary task of defending against a surprise attack and the secondary task of preventing domestic unrest, but their number dropped over time.

A map of Curaçao, including its surrounding area, roughly 70 km from the main coast of Venezuela. Source: hubpages

Oil Reserves

The economic situation would make a drastic turn after 1914 when oil deposits were discovered. Within a year, the Curaçaose Petroleum Industrie Maatschappij (Curaçao Petroleum Industry Company), CPIM for short, a subsidiary company of Royal Dutch Shell, settled on the island. After a century of standstill, there was a sudden increase in employment opportunities, which attracted many workers from the Caribbean, as well as people from Venezuela. The sudden increase of the working class also meant an increase in unrest, mainly in the capital Willemstad. The civilian police corp could not cope with the problems and two slums on the island were no-go areas for any law enforcement.

To deal with these problems, the Dutch government decided in 1927 to replace this police corp and the garrison, which had been gradually scaled down to around 80 men, with 150 men from the Korps Politietroepen, a military police unit from the Netherlands. So, unlike the previous garrison, this unit had as a priority the maintenance of order, and only secondary to defend the island against an attack. The unit arrived during 1928-1929. Nevertheless, the two slums on the island, Rio Canario and Suffisant, were still no-go areas for the police.

Rafael Simón Urbina (right) and Gustavo Machado Morales (left). Source: Maritiem Digitaal

Venezuelan Revolutionary Rafael Simón Urbina

It was in those two slums that the Venezuelan revolutionaries, Rafael Simón Urbina, Gustavo Machado Morales and Miguel Otero Silva, managed to gather a great following among the Venezuelan workers. Although they united to overthrow Caudillo (a military president-dictator) Juan Vicente Gómez in Venezuela, they had different motives. Some, including Urbina, where part of a group of patriots who wanted to liberate Venezuela from Gómez, the others, including Machado, were communists and wanted to establish a communist regime.

After causing too much unrest on Curaçao, Urbina was expelled from the island in 1928, but he managed to return in 1929 under a different name and with a Mexican nationality, which had been given to him by the Mexican consul in Panama. The group of revolutionaries led by Machado had already made extensive plans for an attack on the fort to capture the fortress’ arsenal when Urbina returned on June 1. For unclear reasons, he was directly appointed the leader of the group.

The Attack

On Saturday night, June 8, between 21:15 and 21:30, two trucks with 45 men drove at full speed into the fort. Because the fort also functioned as a police station, the gates were always opened. One group of revolutionaries, armed with two automatic pistols and machetes took the guards by surprise, killed the officer and wounded two other policemen. Simultaneously, another group entered the messroom, where they fatally wounded a Sergeant. A third group, led by Urbina, went to the dormitory, while a fourth group went to the arsenal. At the moment of the attack, the fort was manned by 26 policemen and 9 soldiers. Three soldiers were killed and six other people were wounded. The alarmed Commander in Chief of the military police, Captain A.F. Borren, was taken prisoner when he arrived at the fort.

The loot consisted of 197 rifles, 4 machine guns, 1 binocular, 38 pistols, 75 klewangs (bladed weapons of Indonesian origin), 7,000 cartridges, some machetes, leather clothing, and a reasonable amount of money. After the fort was secured and sealed off from the city by the revolutionaries, Urbina came in contact with the governor of the island, L.A. Fruytier. Threatened by Urbina that the petrol depot would be set on fire, the governor agreed for a free retreat. Just after midnight, 154 revolutionaries (other sources state up to 250) boarded the American freighter S.S. Maracaibo, taking the governor, commander, and several policemen as hostages with them, as well as their loot.

During the early morning of June 9, the revolutionaries unboarded at La Vela del Coro (the capital of Falcón State and the oldest city in the northwest of Venezuela), using the ships’ lifeboats. The Maracaibo was allowed to return to Willemstad with the former hostages, who were humiliated up to the bone when they arrived during the afternoon. If it was up to Urbina, they would have been killed, but Machado prevented that from happening. In the meantime, Urbina’s followers who had stayed on the island were still in large control of Willemstad. The remaining 90 policemen, assisted by civilian volunteers started to recapture the city. Reinforcements were sent during the following days in the form of 40 KNIL soldiers from Suriname, later followed by more marines and KNIL soldiers. The voluntary civilian support would be formed into the Vrijwilligers Korps Curaçao (VKC), 143 men strong.

One of the barricades made by employees of the CPIM. Source: Royal Tropical Institute

Illustration of the C.P.I.M. Improvised Armored Car by Yuvnashva Sharma, funded by our Patreon Campaign

Defense of the C.P.I.M.

Going back to the night of the attack, when the director of the CPIM heard about the attack on the Waterfort, he realized that the refinery was a potential target as well. He immediately arranged defenses in the form of sandbags, iron plates, and similar kinds of obstacles behind which the employees could take defensive positions. He also ordered the construction of armored cars. They were made by adding steel plates to postal trucks, which were largely available at the company. A small attack did indeed occur on that same night, which was successfully dealt with, but the armored cars were not finished yet. A second attack never came, so when the armored cars were ready the next morning, there was no need for them anymore.

One of two armored vehicles near a CPIM building. Note how the mudguards are visible through the gap and the crude way how the armor is cut. Source: Royal Tropical Institute

The second vehicle, the main differences from the other are the installation of the front armor plate, the protection of the headlights and the removal of the canvas roof. Source: Curacao in Ansichten, derived from Overvalwagen.nl

The Armored Cars

In several newspapers and the like, there are mentions of several postal trucks being converted (specific model unknown). Based on photo evidence, there indeed appears to be at least two vehicles converted. It is clearly visible that the vehicles were very hastily assembled, in fact, they were completed in one night. Firstly, steel plating was added over the engine compartment which then folded over the mudguards down to roughly 10 centimeters above ground, protecting most of the wheels, shod with pneumatic tires. Another trapezoid shaped piece folded down over the front, in which two holes were made for the headlights. Another rectangular plate was added below to protect the lower part of the chassis and the front of the wheels. An opening was left so that the front of the mudguards were still visible.

The front of the driver’s compartment was protected by one large sheet of metal with one large horizontal vision slit. The sides of the vehicle were covered in one large plate on each side which was slightly curved at the front. A total of eight shooting holes, four on each side, were also made. Unfortunately, there are no photos of the back of the vehicle, but it can be safely assumed that the doors were in the back. The roof was not armored, as the canvas roof of the original truck was retained.

The postal trucks of the CPIM, two of which would be temporarily converted into armored cars. Source: Royal Tropical Institute

Aftermath

How long the vehicles remained active is unknown, but given their improvised state, they were probably dismantled soon after the threat of an attack was gone. The vehicles were the first armored vehicles ever built in the Dutch colonies, which is made more impressive by the fact that they were built by a private company and not ordered or used by the Dutch government.

The aftermath of the embarrassing attack on the fort was mainly felt by the governor, Fruytier, who got fired in November, and the commander-in-chief, Borren, who was sentenced to one day of prison. However, it was also acknowledged that it could also have been prevented if there was a larger Dutch military presence, which led to an increase in this regard in the area. Only during World War II would armored vehicles serve on the island again, in the form of the Marmon-Herrington CTLS tank, meant to defend the large oil refinery which was a vital oil supplier in the American war effort.

This was the third attempt by Urbina to overthrow Caudillo Gómez, but like the previous two times, he failed. After the Dutch hostages were freed to return to Curaçao, they immediately sent a message to the Venezuelan government in Caracas with information about the number of revolutionaries and their weapons, which allowed the government troops to respond and sent a force to defeat Urbina and his revolutionaries. Both Urbina and Machado managed to escape. Urbina would again try to overthrow the Venezuelan authorities in 1931 and would be involved in several other plots and coups until his assassination in 1950 after a failed kidnapping.

Sources

In de West de Nederlandse Krijgsmacht in het Caribisch gebied, Anita van Dissel, Petra Groen, Van Wijnen, 2010.

De rijke geschiedenis van Curaçao Indianen, de WIC en invasies, Jack Schellekens, Carib Publishing, 2012.

“De overval op Willemstad.”. Haarlem’s Dagblad. 09-08-1929. Consulted at Delpher.

“De blamage van Curacao. Hoe Willemstad in staat van verdediging werd gebracht.”. Haagsche courant. 11-07-1929. Consulted at Delpher.

“De verdediging van de C.P.I.M.”. Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant. 10-07-1929. Consulted at Delpher

Overvalwagen.nl and Overvalwagen forum

One reply on “C.P.I.M. Improvised Armored Car”

I think this is armored truck, not car.