Kingdom of Italy (1932-1943)

Kingdom of Italy (1932-1943)

The tiny concession of Tianjin (written as Tien-Tsin or Tientsin in many period sources) in China was one of several small Italian possessions in the area and was run by Italy between 1901-1947. Italy had been granted the territorial concession in the Xinchou Treaty (also known as Boxer Protocol) on the 7th September 1901 by the Chinese Government following the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) and was occupied the following year. It was just 46 hectares (114 acres) and had a population of only a few thousand ethnic Chinese and under a thousand Italians and other foreign nationals. The shape was roughly rectangular with the southern border on the White River (Pei Ho) (the Italians sometimes had gunboats stationed there); Trieste Street on the west bordering the Austro-Hungarian concession; and Trento Street on the east bordering the Russian concession; Fiume Street formed the northern border and linked to the Beiping (Peking – modern-day Beijing) – Mukden (modern-day Shenyang) railway line through the city, very close to the East Station.

Map of Tianjin from 1912 showing (in green) the small Italian concession

The value of such a small concession is questionable, except that it served as a mark of international prestige for the Italian Empire and allowed the political legation to the Chinese Government to be properly protected.

Ermanno Carlotto Barracks. Sources: Public domain and Battaglione San Marco

In 1925, Italian leader Benito Mussolini created the 600 strong Battaglione Italiano in Cina (Italian Battalion in China) based in this concession. These new troops replaced the slightly more ad-hoc protection for the concession provided previously by the Regia Marina (RN). It was formed from soldiers of the San Marco, Libya, and San George Company’s who were housed in the Ermanno Carlotto Barracks (Italian: Caserma Ermanno Carlotto) named after a fallen Italian hero from the Boxer Rebellion. Along with these troops was a police force of Chinese police led by Italian officers. This constituted a very large military presence for such a small territory, and it was tasked with ensuring that the concession would not be able to be cut off from either Beiping or the sea.

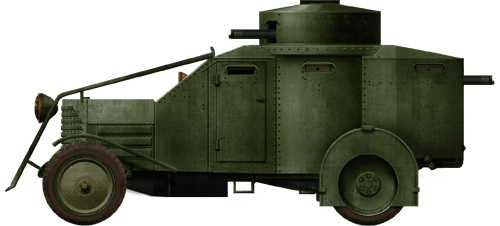

Weapons at the concession around this time included at least two 76mm guns and a quantity of machine-guns, but no heavy weapons. There were continuing problems around the concession and incidents in the years following this (1926) lead to concerns over the safety of Italian citizens living there. To bolster defenses still further, four Ansaldo-Lancia 1ZM armored cars were sent to the concession in 1932 to help maintain law and order.

Four Series 3 1ZM’s on parade on 4th November 1932 in Tianjin. Two 76mm mountain guns are visible by the altar. Source: trentoincina.it

A close up of the 1ZM’s shows them fitted with 3 machine-guns. Source: trentoincina.it

Still from a newsreel of celebrations held in 1935 with a parade of equipment including the 1ZM’s. Source: Luce. This newsreel can be found at the end of this article.

By 1936 though, some troops were transferred away from the concession to Africa, leaving the force much reduced. The events of 1937 changed this situation when Japanese forces attacked the Chinese held part of the city of Tianjin and occupied it. This led once again to significant fears for the concession being attacked by either Chinese or Japanese troops, and consequently, a new delivery of soldiers – a battalion of the Grenadiers of Savoy (Granatieri di Savoia) – from Italy arriving in the concession. As things settled down by the end of 1938, most of these troops were once again withdrawn or relocated. By the end of the 1930s, the entire Italian military presence in China amounted to less than a 1000 men divided between Tianjin (~400), Shanghai (215), Shanhaiguan (25) and Beiping legation and radio station (15), along with an unknown number of naval personnel.

Some of the soldiers of the Granatieri di Savoia arriving by lighter to the riverside on 14th September 1937. Photo collection Karl Kengelbacher

The Lancia 1ZM. Illustration by David Bocquelet, modified by Bernard ‘Escodrion’ Baker.

World War II

Italy entered World War Two on the side of the Axis in June 1940. Initially, this did not affect the concession of Tianjin significantly, as the now-enemy forces of Great Britain had abandoned its concessions in August 1940. Only in the middle of 1941, was the concession once again felt to be under threat, and as a result, and consequently, reinforcements were despatched.

Nonetheless, the concession, being surrounded by the Japanese with whom they were allied, was relatively calm, but the events of September 1943 changed everything. Italy had signed an armistice with the Allies and officially capitulated on the 7th, becoming a co-belligerent force fighting with the Allies against a mainly fascist loyalist force called the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (RSI) and the German occupiers in what was effectively a civil war in Italy. What this meant for Tientsin, was that the former Japanese allies now became potential enemies. The Italian troops stationed in China were given specific orders not to cause any trouble or engage with the Japanese forces and to scuttle any ships which would otherwise not be able to reach an Allied controlled port. Thus, the Lepanto, the Carlotto, and the Conte Verde were scuttled in Shanghai.

Unusual overhead view of the four Lancia 1ZM’s lined up in the concession.

Despite efforts not to aggravate the Japanese, the position in Shanghai changed on 9th and 10th September 1943, when the troops stationed there were seized by the Japanese. Those who chose to collaborate were put to hard labor, with the remainder of the men being sent to POW camps along with other Allied soldiers. The troops stationed at Beiping radio station, despite orders not to resist, fought against the Japanese until they could destroy the station and all documentation which might help the new adversary. The tiny force of just 100 sailors and soldiers led by Captain Baldassare held-off over 1,000 Japanese soldiers and some light tanks until surrendering on the 10th. They received very harsh treatment from the Japanese for their defiance, but given the equally harsh treatment given to some troops who ‘stayed loyal’ to the Axis, perhaps it did not matter anyway.

In Tianjin, the situation was equally confusing. The troops in China had no knowledge about the armistice of the 7th September and thus had no time to prepare. The senior officer commanding Italian forces in Tianjin at the time was the Captain of the Frigate Carlo dell’Acqua, who had at his disposal about 600 men, 300 rifles, some pistols, and about 50 machine-guns of various types. Four 76 mm guns made up the most powerful weapon in their arsenal along with the four ancient Ansaldo-Lancia 1ZM armored cars fitted with the FIAT Model 1924 6.5 mm machine-gun, and some unarmored motor vehicles. With plenty of ammunition and food for a week, he was going to have to face down the Japanese.

The Japanese under Lt. Col. Tanaka had over 6,000 men with numerous light armored vehicles and reportedly some tanks, as well as two gunboats. The Japanese provided an ultimatum to the Italian defenders to surrender, but this was rejected resulting in the Japanese firing some light artillery to attempt to intimidate the defenders. The Italian loyalty was fractured, with about a third of the troops wishing to remain loyal to the fascist regime but the rest not. Surrounded, outnumbered, and facing annihilation by the Japanese, the contingent surrendered. To have resisted would have been futile as it would have resulted in a lot of damage to the area and deaths of civilians for no purpose. The troops who surrendered elsewhere were often treated very badly by the Japanese by either being sent to POW camps or forced to carry out hard labor, so there was no good option available for the soldiers.

Having surrendered, their weapons and armored cars would have therefore fallen into Japanese hands, as at this time there was little time to destroy the equipment. No pictures are known to show the Japanese using these vehicles, although it is possible they would have been reused within the city for policing. No trace of them survives, so they were most likely scrapped then or subsequently.

Therefore, by 10th September the Japanese had completely occupied the Italian concession of Tianjin. Shortly afterward, the RSI chose to officially cede the concession over to the Chinese puppet state of Wang Jingwei. That Japanese puppet state would eventually fall to the forces of Chiang Kai-Shek. All rights to Tianjin were formally ceded by Italy on 10th February 1947 by the government of the Republic of Italy to the government of the Republic of China. Those Italian troops who survived the treatment of the Japanese finally returned to Italy in 1946.

Sources

Automitragliatrici Blindate E Motomitragliatrici nella grande guerra, Nicola Pignato

Cronologia.leonardo.it

Marina.difesa.it

Italy’s Encounters with Modern China: Imperial Dreams, Strategic Ambition: ‘The Italian presence in China: Historical trends and perspectives 1902-1947, Guido Samarani

From the Bulletin of the Historical Office of the Navy March-June 1989, (written in 1933 by the Ten. Fanteria Amleto Menghi), San Marco

Italian Armed Forces in China 1937-1943

Self-portrait in a convex mirror: Colonial Italy reflects on Tianjin, Maurizio Marinelli

Making concessions in Tianjin: heterotopia and Italian colonialism in mainland China, Maurizio Marinelli

Italian Surface Units in Far East 1940-1943, Alberto Rosselli at www.icsm.it

2 replies on “Lancia 1ZMs in Tianjin, China”

Fiume street was named after the city of Fiume (nowadays called Rijeka and part of Croatia), which at time was under Italian control, and not after a generic river.

Fascinating story!