United Kingdom (1914-1915)

United Kingdom (1914-1915)

Landship – Design Only

Overlooked by most histories of the era of early armor, Robert Macfie was a visionary who first pressed the use of tracks to the Landships Committee at a time when ‘big-wheel’ machines were seen as the solution to the problems on the Western Front, namely barbed wire and machine guns. Almost unknown today, Robert Macfie designed what was to be one of the first tracked Landships.

Born on 11th November 1881 in San Francisco, the American-born son of a sugar baron, Macfie took an early interest in military matters outside of the family sugar business. Aged just 17 or 18 years old, he enrolled in the Royal Naval Engineering College, at Davenport, England studying naval design. After this, he went back to help with the family’s sugar business before settling in Chicago in 1902.

Around this time, he began an interest in aviation and was back in Britain by 1909 building his own aircraft and testing them at Fambridge in Essex. It was during his endeavours in the then brand-new field of aviation that he met Thomas Hetherington, a man later connected with landships in his own right.

His attempts at getting into the aviation business, however, were not a success. He was back on the family sugar plantations in the years before the outbreak of war and it was there that he became acquainted with the Holt agricultural tractor.

When war was declared in August 1914, Macfie returned to Britain once more. He immediately sought out his contacts from his aviation days advocating for the use of Holt-based tracked vehicles, and was referred on to Commodore Murray Sueter, in charge of the Royal Naval Air Service (R.N.A.S.), which at the time was operating armored cars, the primary mobile armored force for the Army.

Macfie had a design for a tracked vehicle sketched out and, even without official sanction or support, was seeking a manufacturer. As such, he approached Mr. Arthur Lang, a well-known manufacturer of propellers, who gave Macfie an introduction to Captain Swann, Director of the Air Department. Armed with the previous referral and a recommendation from Mr. Swann, Macfie got to see Commodore Sueter and presented to him a design for an armored vehicle based upon the Holt agricultural tractor, identified as a ‘caterpillar’.

Despite his engineering training and education, he was still an outsider in military terms. Wanting his designs and ideas to be taken seriously, Macfie made what could easily be his greatest professional error. He enlisted in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (R.N.V.R.) under a temporary commission as a Sub-Lieutenant in the belief that doing so would provide him with the contacts and credibility or ‘standing’ he might need. What it did though was to stymie his work and pigeon-hole him into armored car work and within a rigid military command hierarchy. On the plus side though, within this hierarchy, his immediate superior officer was his old friend Captain Thomas Hetherington, who he knew from his days with aircraft at Brooklands before the war.

Layout

The original sketch presented to Sueter in 1914 by Macfie was described as:

“triangular in side elevation, with a long base on the ground and a cocked-up nose to help it get a grip on banks or parapets. It even had a pair of trailing wheels aft, to keep it from swinging – just as our tanks had when they went into action two years later” and with a “comparatively long track and a comparatively short nose, and the nose is of such a nature as to give a climb…. There are three wheels, and the caterpillar goes round the third so that you get a flat base and a nose”

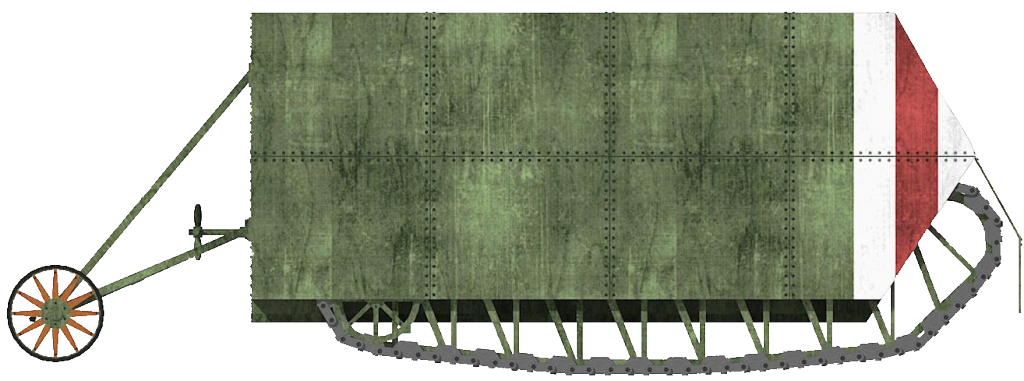

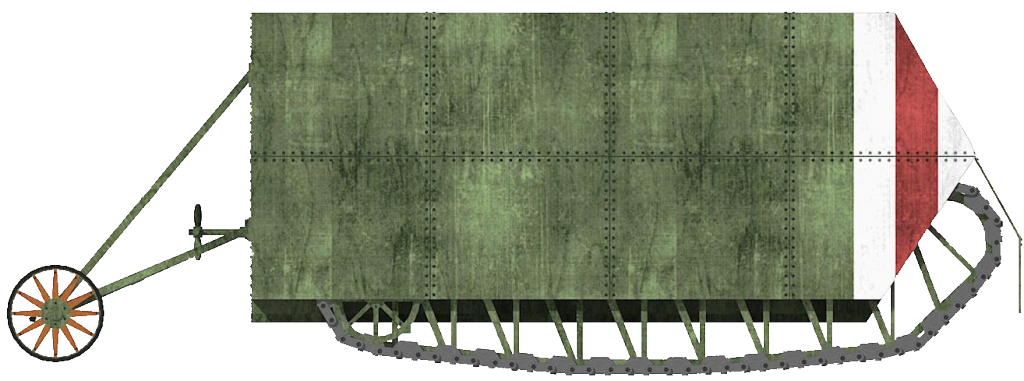

The vehicle was of a simple outline, being a rectangular box with a flat rear and sides and a wedge shape at the front. Hanging from the front was a large armored panel that descended at the same angle as the glacis until approximately two-thirds of the way down the height of the body. Below this, panel was a hinged flap allowing the tracks to be protected but flexible so as to not interfere with obstacle crossing.

At the back of the vehicle was a single fixed propellor intended to provide drive in the water and connected directly to a power take-off from the drive shaft.

Drive for the tracks was provided by a single-engine located centrally inside the hull, with the driving position directly behind. Steering for the driver was affected by means of a large steering wheel to his front but connected via a linkage to a pair of retractable trailing wheels at the back fitted with an Ackermann steering system.

The vehicle itself was fabricated from a framework to which panels of armor plate were fastened, presumably by means of bolts and rivets but creating a watertight body. This body was buoyant in water and the drawing identifies the metacentric height as very slightly below the centre-line of the vehicle’s body.

The most unusual element of the design though was the tracks. Despite being based on the Holt system, the track system designed by Macfie did not use wheels. Instead, it used a unique system whereby the tracklinks were a flattened ‘U’ shape with a square base. The base fitted onto a single smooth track guide running the full circumference of the track unit which was supported by spars, much in the same style of an aircraft. The track was driven though in a similar manner to the Holt system with a large 12-tooth drive sprocket at the back driven by a chain from the transmission located at the back of the vehicle.

No armament was specified for the Experimental Armoured Caterpillar, possibly because it was intended to be an experimental vehicle on which a future landship-of-war would be developed. As it stood though, with the driver at the back, it would have required a minimum of at least two men, a driver and a commander (who could see where to go, to operate the vehicle) and then more men for any weapons being carried.

Hauling Guns

Macfie had no success at persuading the authorities to accept his Holt-based caterpillar design, but on 2nd November 1914, whilst working as a Field Repair Officer at Wormwood Scrubs and then the nearby Clement Talbot Works, he saw a clipping from that day’s Daily Mail newspaper. The newspaper had an image showing a Holt Caterpillar in use headed ‘German Convoy entering Antwerp’ with the caterpillars hauling heavy naval guns. This article inspired a report from Macfie on 5th November 1914 to Sueter, once more pressing Macfie’s conviction over the use of tracked vehicles, albeit this time for hauling guns.

The plan was not armored though. Effectively, it was a train of 6 Holt tractors working together to haul a 85-ton (86.4 tonnes) load (the weight of a 12-inch naval gun and limber).

Further to the gun-hauling idea was that one of these Holt tractors could be gainfully employed in recovering the armored cars of the R.N.A.S., which had a habit of getting stuck when off-road or on what still passed as roads.

Sueter, however, had no interest in either option for the Holt tractor, but the die had been cast by Macfie and he had succeeded in convincing Hetherington of the validity of his ideas, although Hetherington too had his own ideas quite apart from those of Macfie.

Holt Redux to the Committee

Despite having discounted the idea of the Holt tractor for any use regarding an armored vehicle, a gun-hauler, or as a recovery vehicle, Sueter, in January 1915, asked for a report on Holt tractors. When he got the report back at the end of January 1915, Sueter must have been interested in the potential of the Holt track idea at least in principle, as he records in his own memoir that he saw Churchill several times bemoaning the problems of the tyres of his armored cars off-road and suggested that tracks might be more suitable.

It was then perhaps Macfie’s prior badgering about the merits of the Holt that proved most influential then, because when, in February 1915, a Landships Committee was being formed, Macfie was invited to attend at the behest of Hetherington. The 22nd February 1915 meeting was the first official meeting of the Landships Committee and it was to be the only time Macfie was in front of the committee.

The most significant person there other than Macfie with relevant experience to the problem of traction off-road and in mud was Colonel Rookes Crompton, a leading expert in wheeled traction. Crompton brought an idea for a giant wheeled machine and he would not be the last to suggest such a wheeled scheme, but Macfie was different. Macfie once more suggested the advantages of a tracked vehicle and was persuasive enough that Crompton acknowledged the advantages of tracks over wheels. Thus the die was cast, tracks were to be the primary solution to off-road traction for an armored vehicle and the man primarily responsible for this was Macfie.

The meeting was also a split between Hetherington and Macfie. Hetherington had his own wheeled battleship scheme he wanted to pursue and Macfie was wedded to tracks. Macfie then took his plans to Commander Boothby (R.N.A.S.).

Bootby was also won over by the idea of tracks and via Sueter arranged for Macfie to pursue a tracked vehicle as a test. Not a landship as originally planned, but the conversion of an old lorry into a tracked vehicle following a report from Macfie in April 1915.

April 1915

Macfie had no success with his traction schemes other than in persuading the Landships Committee of their virtue. He did have a task with the tracked truck but his mind was still on a tracked landship. To this end, on 13th April 1915, via Boothby, he made yet another submission, this time envisaging how the as yet non-existent landships could be used in combat suggesting:

“One form of attack I would suggest is as follows:

At dawn two columns of caterpillars would seize a zone of the enemy’s trenches – previously surveyed by Aeroplane – by getting astride them and killing everything in Zone A by enfilading fire. Immediately after this a horde of cavalry and horse artillery could pour through and seize the enemy’s base… I am aware that machines are proposed which will be armoured against rifle and Maxim fire which are to carry parties of soldiers to the trenches whereupon doors are to be opened and the men pour out. I would submit that this plan fails to deal effectively with the enemy’s artillery and that further only the front line of enemy’ can be dealt with in this way. Again caterpillar construction and operation like other branches of engineering is not as easy as it looks. Engineers without any experience of this work, no matter how distinguished in their own fields, are no more likely to succeed at it than a locomotive expert would be likely to succeed at hydroplane construction at the first attempt, or vice versa, without previous study or experience”

As well as this theory of attack, Macfie had also given serious consideration to the problems of steering saying:

“steering with wheels is easy, because a wheel touches the ground at one point, whereas a caterpillar presents a whole surface to the ground. Again, in a wheel the only rubbing surfaces are at the centre, well away from grit and dirt, which is also thrown away from the hub by centrifugal force”

Macfie was presenting his idea for a tracked and armored vehicle steered by wheels at the back and the truck conversion was as much a test of tracks as technology as they were to consider the issues of steering a tracked vehicle.

Nesfield’s

The work on the tracked truck took place at Messrs. Nesfield and Mackenzie along with the works director there, Mr. Albert Nesfield. The relationship between Nesfield and Macfie though was a thoroughly dysfunctional one and was the subject of acrimony during the post-war enquiry into the invention of the tank. The primary cause of the dysfunction seems to have a relatively straightforward clash of ideas. Macfie had to construct a tracked truck at the Nesfield and Mackenzie works and at the same time he was working on his landship idea. At the same time, Nesfield, with no previous involvement in matters, created his own ideas for a tracked vehicle borrowing extensively from Macfie.

When Macfie finished his model of his landship in June 1915, he took in to Sueter to show him. To his dismay, Macfie found that the very same model had already been brought to his offices on 30th June and shown to the Landships Committee (a fact disputed during the post-war commission). Two models were in fact made, a wooden one, and an aluminium one made on Macfie’s orders, and for security reasons, according to Macfie, these were later destroyed. Another model, powered by a pair of electric motors, was presented to the Royal Commission in 1919/1920. Macfie explained exactly why this model, even without trailing wheels was his:

“the model was never finished at Messrs. Nesfield and Mackenzie’s… but the state into which it had finally got when it disappeared was a body, open at the top, to represent the armoured body and two triangular tracks on either side made out of ordinary bicycle chain. Each track was driven by a small electric motor…I adopted that form of steering [one electric motor for each track] because it made a good demonstration form of steering. It would be very difficult to make a model which would be an effective demonstration model by using any other form of steering”

On or about 2nd or 3rd July, Macfie came to speak with senior officers at the Admiralty about his tracked vehicle ideas and asking for them to be taken over under the Defence of the Realm Act (D.O.R.A.). When he walked into the room to speak with them he found senior officers examining his model and sternly rebuked them saying:

“where on earth does this come from; this is mine, and I spent the last week looking for it”

Macfie was informed that the model brought there by some representative of Messrs. F.W. Berwick and Company, (colleagues of Mr. Nesfield) but Macfie’s anger was understandable. This unfinished model, still missing the trailing wheels, had been locked in a safe beforehand in Mr. Nesfield’s office and now had, after vanishing from there, mysteriously turned up at the Admiralty, delivered by colleagues of Nesfield. Macfie promptly seized the model back.

Macfie took this model back to the Clement-Talbot Works, the Headquarters for the Armoured Car Squadron and complained directly to Commander Boothby about what had happened. Boothby then sanctioned and approved for all work at Messrs. Nesfield and Mackenzie to cease immediately and Macfie set about finding a new site to finish his project. The working relationship between Macfie and Messrs. Nesfield and Mackenzie was to be dissolved. Boothby was thus in absolutely no doubt as to what was going on and acted decisively.

Macfie, with an armed guard to accompany him, then seized all of the remaining elements of the tracked work, and the as-yet unifinished tracked truck from Messrs. Nesfield and Mackenzie. For security reasons, all of the remaining drawings and models which were not handed in were burned, although in hindsight, this move, whilst efficient to maintain operational security, left Macfie with very little evidence in the post-war enquiry to refute the claims of Mr. Nesfield.

Angularization

The important element of Macfie’s design and the one over which Mr. Nesfield was claiming invention was referred to as ‘angularization’. This term referred to the shape of the track at the front of the vehicle. On the Holt track system, the track was effectively flat with the leading section close to the ground, but Macfie’s design had a raised front end. This raised front end would permit the vehicle to climb a higher parapet or cross a trench which was wider than that which could be crossed by a low-fronted track.

This development was later summed up by Sueter during the enquiry into the invention of tanks saying:

“No one regretted it more than I did that Lieutenant Macfie failed me in producing an experimental landship, but the angularized track invention I am certain made the Tank the great success it became on active service. What an opportunity Lieutenant Macfie and Mr. Nesfield had. It was no fault of mine that they did not become as successful as my other Armoured Car Officer Lieutenant Wilson and Mr. Tritton of Messrs. Foster and Company were with their tank work”

Sueter refused to take any blame for the problems between Macfie and Nesfield, but Macfie was also undoubtedly an abrasive man in his own right and had rubbed Alfred Stern (the growing power within the Landships Committee) up the wrong way.

He would not see his unfinished tracked truck again, and in December 1915, his commission was ended. Macfie was to have nothing more to do with the official development of Landships or tracked vehicles of any kind during the war.

Conclusion

Despite the failure of Macfie to have the Landships Committee adopt his original design, he did have one significant success, namely convincing the authorities to pursue tracked vehicles instead of wheeled schemes for a landship albeit basing his ideas on the Holt chassis at the time. His design was not a success and the plans he burned for security purposes could have provided him with the evidence he needed to properly submit his claim in 1919 to the subsequent Royal Commission. As it was, he was awarded just a fraction of the money he may have been properly entitled to which Nesfield had also laid claim.

Despite being denied the chance to finish his tracked truck or to see his landship come to fruition, Macfie was not finished with tracked vehicles. In fact, he would go on to design more tracked vehicles, but sadly for him, these too were failures. Macfie returned to America after the war and died in New York on 9th February 1948.

Illustrtion of Macfie’s 1915 design, produced by Mr. R.Cargill

Specifications |

|

| Crew | 2 (driver and commander) and weapons crew as required |

| Armament | At least 2 Machine guns |

| Armor | Bulletproof |

Sources

Hills, A. (2019). Robert Macfie, Pioneers of Armour Vol.1. FWD Publishing, USA (Available on Amazon)

Proceedings of the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors: tank 1918-1920

Service Record Royal Naval Air Service 1914-1916: Robert Macfie

Robert Macfie (Pioneers of Armour)

By Andrew Hills

The foundations and principles of modern armoured warfare did not appear out of a vacuum, and nor did the machines of WW1 and WW2. Their development was full of false starts, failed ideas, and missed opportunities. Robert Macfie was a pioneer in aviation at the turn of the century followed by work with the Landships Committee on tracked vehicles to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Although his tank designs never saw combat the work he started was carried on by other pioneers and helped to usher in a dawn of armoured and mechanised warfare.

6 replies on “Macfie’s Landship 1914-15”

It is odd that the RNAS were initially involved in tank development, as their armoured cars had only one role – to rescue downed pilots!

Thank you for doing an article on these! I have been researching them for a while and had trouble finding information.

The new layout it’s eye hurting!

please change new color scheme back white hurts eyes

I second DMD and randal! The new site-layout is hard on the eyes. I liked the old one better.

That’s my grandfather you’re writing about and I have plans of some of his inventions. Excellent article. Would love to connect!