Czechoslovakia (1933-1945)

Czechoslovakia (1933-1945)

Tankette – 74 Built

The Tančík vzor 33 (Tankette pattern 1933), also known as the P-I, was a Czechoslovak tankette that started life as a license-produced copy of the Carden-Loyd Mk.VI. Due to the British vehicle’s bad performance, the Tančík vz.33 ended up as an improved version. Despite this, it was still not up to the standards the Czechoslovak Army wanted it to be, but political pressure caused an order to be placed at the manufacturer. Including four prototypes, a total of 74 Tančíks were built at the factory of Českomoravská Kolben-Daněk (ČKD) where the vehicle was also known as AH. Although designed as a light reconnaissance and combat vehicle, it failed to live up to the standards required for these tasks. Serving in the Czechoslovak Army from the beginning of 1934 onwards, forty vehicles fell in German hands in 1939 after the occupation of Czechoslovakia. The other thirty remained with the Slovak Army throughout the Second World War.

Origins: the British Carden-Loyd Mk.VI

In October 1929, a Czech delegation, led by Lieutenant Colonel Bedrich Albrecht, visited the Vickers-Armstrong Ltd. plant in Britain. Albrecht was head of the III. Department of the Military Technical Institute (Vojenského technického ústavu, shortened to VTÚ). This department was responsible for evaluating military innovations and advised the army whether or not to follow up on these innovations. One of these new innovations was the Carden-Loyd Mk.VI tankette, which was described as a cheap and effective lightly armored vehicle to support infantry divisions. Albrecht, impressed by the small and cheap vehicle, strongly recommended the Ministry of Defence (Ministerstvo národní obrany, shortened to MNO) to put this kind of vehicle into service.

After consideration, the Ministry agreed to let the domestic firm of ČKD obtain the license and buy three vehicles from Vickers. After these vehicles had arrived in Czechoslovakia during the spring of 1930, ČKD was ordered on May 14 to build four copies, designated CL-P (Carden-Loyd-Praga). Production commenced immediately and, while all four were ready by the end of September, they came too late to participate in the autumn field trials. Despite this setback, the three Carden-Loyds bought from Vickers were tested extensively.

Field Trials with the Carden-Loyd Mk.VI

During the 1930 autumn field exercises of the army, the CLs participated as a platoon and their performance, both on a tactical and technical level, was reported in detail. On a technical level, the vehicles performed very poorly. Their low ground clearance caused the ride to be very rough and it proved very difficult to ride on roads with deep ruts. In the countryside, roads were often nothing more than cart tracks. In most cases, the tankettes were too wide to drive on these tracks and had to go off-road, where large rocks easily caused damage to the low engine housing. Furthermore, driving along slopes was almost impossible, as the tracks were very easily thrown off. This also often happened when the tankettes tried to overcome obstacles. For instance, during one maneuver, when a vehicle tried to drive from the road onto the terrain, a track was thrown off by a bump on the side, which meant twenty minutes had to be spent to get the vehicle back on track. Another vehicle got stuck when the bottom of the vehicle slid on the middle part of the road while the tracks lost traction in deep ruts.

This bad performance caused both mental and physical suffering to the crew, who were gusted inside the vehicle during movement and the technical problems caused the crews to distrust their vehicles which lowered their morale. During movement, there was so much noise inside the vehicle, caused by the suspension and engine, that communication was practically impossible. Another problem was that the crew could not see each other. The large vision openings in the front, although providing a reasonable amount of vision, also reduced the safety of the crew. A rather bizarre anecdote claims that, while several officers, including Lt.Col. Albrecht, were examining the vehicle at the courtyard of the VTÚ, an officer noted that enemy bullets would easily go through the large vision openings, hitting the crewmember in the head, to which Albrecht seems to have replied: ‘you are right, but that man would have been miserable anyway, it is better if he was taken by God’.

Another problem with the vehicle was the machine gun. Its placement only provided a very narrow firing arc which reduced its effectiveness significantly. Furthermore, whenever the gunner had to reload the machine gun, he became partially exposed because the ammunition was stored in the storage compartments on the outside of the vehicle, greatly reducing his personal safety. It was reported that the best solution to this problem was to place the gun in a small turret which would also increase the gunner’s protection.

On a tactical level, it was concluded that the vehicles could be successfully used in conjunction with infantry or cavalry to attack unorganized enemy positions and were able to target positions over a greater range, but it was revealed that the vehicles did not meet the requirements for a reconnaissance vehicle, let alone it being used in the role of a conventional tank or deployment against enemy armored vehicles, which were fully out of the question. Comparative trials with wheeled armored vehicles, namely the OA vz.30 built by Tatra that was in development around the same time, concluded that the armored cars performed better in almost every case.

The End?

With the tankettes performing this badly, ČKD feared no orders would come in, which would result in a financial problem. To prevent this from happening, a quick promise was made to make an improved design and rebuild one of the CL-Ps after this new design. Work was undertaken over the course of 1931 on the vehicle which bore registration number NIX-225. To differentiate from the CL-P, the vehicle was designated P-I, according to the new naming system the Czechoslovak Army had adopted. P stood for the manufacturer, in this case, Praga, part of ČKD, and I represented the type of vehicle, in this case, tankette.

Starting from the bottom, the track guidance system was reworked in order to decrease the number of times the tracks were thrown off. The armor layout was completely reworked, the radiator at the rear was protected by adjustable blinds instead of doors, the crew compartment was enlarged so that ammunition could be stored inside the vehicle and the crew was now able to see each other, which improved their communication possibilities. Compared to the CL and CL-P, the crew positions were swapped around, with the gunner now sitting on the left and the driver on the right side. However, the original driving controls were also retained on the left side, so when necessary, the gunner could drive the vehicle as well. The gunner received a 360-degree rotatable periscope, greatly improving his visibility. The vz.24 heavy machine gun was replaced by a ZB vz.26 light machine gun in a new sliding armored shield, providing a much larger firing arc, but this decreased its firepower. 2,400 rounds could be stored inside the vehicle in magazines of twenty rounds stored in larger boxes. The armor was thin, with only 9 mm at the front, 6 mm at the sides, and 3 mm on the bottom.

Trials, Again

After completion, the rebuilt vehicle was soon subjected to extensive trials in the period 1931-32 by the military administration. Special attention was given as to whether the faults in the original Carden-Loyd design had been resolved. The vehicle drove 4350 km, during which it was observed that faults were still common, but overall the vehicle performed much better. Due to the enlargement of the wheels, ground clearance was increased by 3 cm, from 20 to 23, and although a small change, it was received positively by the VTÚ.

After these trials, the other prototypes were rebuilt according to the first one, but the armor thickness was requested to be increased from 9 to 12 and from 6 to 8 in other places, and a second machine gun to be added on the driver’s side to increase the firepower, which was considered too low. The three army prototypes were handed over to the armored division based in the city of Milovice on October 17, 1933. The fourth was kept at the factory.

The Order

Despite the better performance, army officials had still not found a tactical use and questioned the vehicle’s value. As such, a group of officers, led by Colonel Antonín Pavlík, commander of the armored unit at Milovice, argued that the vehicles were tactically worthless, technically not satisfactory and should therefore not be acquired. They were opposed by Albrecht, who was backed up by Minister Bradáč and, as the minister had the most influential voice in decision making, it is no surprise the opponents fought a lost cause. According to Albrecht and thus the Minister, the design was ready to be implemented and they did not want to let down the firm of ČKD, which was heavily invested in the project at the time and thought the denial of a contract would cause a scandal.

An order for seventy P-I tankettes was placed on April 19, 1933, which were after June 30 referred to as Tančík vzor 33. A price was negotiated with ČKD of 131,200 CZK a piece and 32 pounds for the license fee. ČKD promised to deliver 40 vehicles by the end of the year and the other 30 by September 1934. However, due to problems with the quality of the armor plating, production could only be initiated until November 9, and the first 10 were only accepted on January 9, 1934, and taken into service on February 6. In March, two batches of 10 each were accepted, followed by a batch in April, two batches in August, and the last batch in October. The vehicles passed the driving tests on the road from Prague to Milovice and back. However, some failed the armor tests and were penetrated by regular bullets. Despite this being a problem, the holes were riveted and never looked at again. The vehicles were declared ready for service.

The Final Design

The basic layout of the chassis and suspension still closely resembled that of the Carden-Loyd. It featured front driving sprockets, with thirty teeth and a jaw brake system that was mass-produced and used in the Praga Alfa car. The tensioning wheels at the back were mounted in spring-loaded brackets. These tensioning wheels were ordered to be made out of bronze but, in the end, an alloy of two different materials was used. On each side, four steel wheels, shod with rubber, were placed. They were grouped together in pairs and suspended by leaf springs. On the top, the tracks were guided by an ash wood beam with a 6 mm thick steel strip. The tracks consisted of 128-130 links, depending on how far the tensioning wheel was placed, which were connected to each other with individual pins.

The vehicle was propelled by a Praga AH 1.95 liters engine (bore 75 mm, stroke 110 mm) which produced 23 hp (16.9 kW) at 1700 rpm. At 3000 rpm, the power went up to 31 hp (22 kW). At full throttle, the tank could reach a speed of 32 km/h on-road, reduced to 20 km/h on dirt roads, or 15 km/h off-road. The air to cool the engine could enter through the blinds both at the front and rear of the vehicle. Just behind the engine, a beehive-type cooler was placed and behind this, a fan that sucked air in. The fan was protected by mesh, in case anything would enter the vehicle through the blinds. The exhaust muffler was mounted beside the rear right fender and above it. An exhaust siren was mounted which could be controlled by the driver. The sirens could be used to communicate with other vehicles in the platoon. The gearbox came from the Praga AN truck and featured four forward, and one reverse gear. The differential and drive axles came from the Praga Alfa cars. In front of the differential, a reduction was placed that could be enabled in case of off-road driving.

The fuel tank, with a volume of 50 liters, was placed behind the gunner’s seat. It supplied the carburetor in two independent ways with fuel, either by gravity or with an electromagnetic ‘Autopulse’ pump. The pump was needed to ensure enough fuel would reach the engine if the vehicle was tilted, while if the pump would fail, there would still be the gravity method. The engine could be cranked up. The crank was slid into a hole under the rear blinds which was protected by a hinged cover but a small electric starter engine was located inside the vehicle as well.

The crew compartment, which doubled as the engine compartment, was cramped and uncomfortable. The engine produced a lot of noise, bad air, and high temperature. Furthermore, a wide variety of equipment had to be stored inside the vehicle, including tools, spare parts, parts for the weapons, and ammunition, which reduced the movement capabilities of the two crew members, the driver on the right and the gunner on the left. Both could enter through hatches on top of the vehicle. The driving controls were duplicated on both sides. It featured three foot pedals for clutch, brake, and throttle. The vehicle could single-handedly be steered by a lever which, when moved either to the right or left, would cause braking of either the right or left differential shaft. This system was a direct copy of the British system in the Carden-Loyd. The driver had direct vision through an opening that could be closed with a small hatch. This hatch could be fixed in any position. The hatch itself featured a smaller vision slit that was covered with bulletproof glass. The gunner could look out through two vision slits placed in the movable gun shield. These were protected with bulletproof glass as well. If the bulletproof glass would be damaged, the slits of both the driver and gunner could be covered with an additional armored plate with a very narrow and long vision slit. Besides these front-facing viewing slits, there was one on either side and two at the back. Furthermore, the gunner had a monocular periscope, placed in a ball mount in the top hatch. It had a 35 degrees field of view. They were made by the German company E. Busch Opt. Werke and delivered by the firm of J.Krejčí, apart from ten that were delivered by Optikotechna from Přerov.

Further features on the outside of the vehicle were the headlight that could be placed on the front of the vehicle above the blinds, towing hooks on both the front and back capable of withstanding a force of 2000 kg, and engineer equipment that included a shovel, a pickaxe, and a five-meter long rope.

Armor and Armament

The armored hull, with the plating provided by Huť Poldi (Poldi ironworks), with various thickness, was of riveted construction, except on a few places where it was bolted to the frame if the armor had to be able to be removed for maintenance. The vertical plates in front of the crew, the lower glacis and the extruding differential cover were 12 mm thick. The blinds at the front were 10 mm thick. The sides and the rear, including the blinds, were 8 mm thick. The sloped parts of the roof and the upper glacis were 6 mm thick, while the underside and mudguards had a thickness of 5 mm. The roof, including the hatches, was the thinnest with only 4 mm. Fire testing proved that the frontal armor could withhold 7.92 mm bullets from a distance over 125 m, the sloped sheets from 100 m, the bottom from 150 m and the top from 250 m. The armor would resist regular infantry ammunition from 50 m onwards.

The original armament of the CL-P consisted of a Schwarzlose re-chambered to fire Mauser 7.92 mm ammunition. This machine gun was known as the vz.24, but due to the problems with it mentioned earlier, a replacement was sought. When production was ordered in April 1933, the armament was considered to consist of one light vz.26 machine gun and a heavy machine gun, but by November, it was still unknown which heavy machine gun was to be chosen. Several options failed, the air-cooled CZ vz.30 overheated during a continuous fire and the heavy ZB-32 machine gun was too large. As such, the decision was made to temporarily replace the heavy machine gun with a second vz.26 light machine gun. However, a replacement was never found, which made the armament of two light machine guns a permanent feature.

The main gun was placed in a movable armored shield that had a firing arc of fifty degrees and an elevation of 16 degrees. Directly to the right of the gun, a small aiming hole was located. The secondary gun was operated by the driver with a trigger in front of him, connected to the trigger of the machine gun to his right. 2,600 rounds of ammunition were carried in boxes. Of these, 400 were fitted with a steel core which were to be used against lightly armored targets. When fired, the cartridges fell into canvas bags attached to the guns to be disposed of later.

Registration Numbers and Camouflage

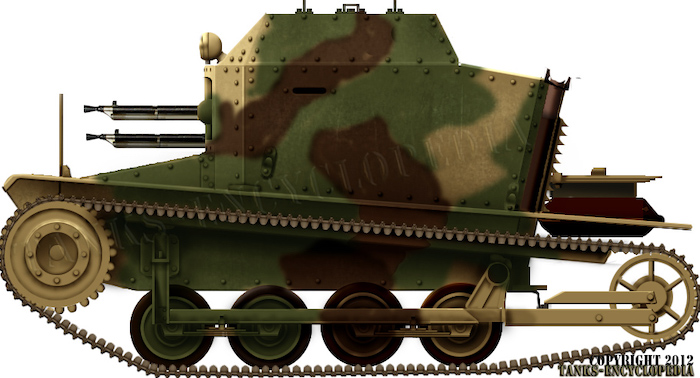

The four initial CL-P prototypes were painted in a regular army green color and painted ivory on the inside. Apart from the factory prototype, the other three received army registrations: NIX 223, NIX 224, and NIX 225. In December 1932, these registrations were changed to 13.359, 13.360, and 13.361 respectively. The serial produced vehicles received registrations from 13.420 to 13.489. When taken into service, all vehicles received a brown-green-yellow camouflage pattern. The pattern was identical on all vehicles which makes it near impossible to identify an individual vehicle on a photograph when its registration is not directly visible.

A Problematic Start

While the vehicles were gradually taken into service over the course of 1934, it was quickly proven that the Minister should not have listened to the vehicle’s greatest advocate, Albrecht, but to Pavlík and the other officers who did not believe the tankette would be a valuable addition to the army in its envisioned role. When most of the 70 vehicles took part in the big army exercises at the end of 1934, the concerns raised during the development process again became reality. Firstly, the crew could not properly function. The driver was busy driving, and could not operate his machine gun in any effective way, while the gunner could not effectively use the machine gun when a speed of 10 km/h or more was reached. Furthermore, the vehicles still experienced difficulty on rough terrain and when operating in platoons of five. Cooperation with the help of signal flags and horn signals proved to be very difficult and thus ineffective, rendering the vehicles basically useless for any effective well-organized and cooperative combat. While the crew was busy performing their tasks, they could not give enough attention to their surroundings, rendering the vehicles useless for reconnaissance as well.

There were also serious problems with the propulsion of the vehicle. To sort things out, a meeting was held on November 23, which was attended by representatives of the Ministry of Defence, the VTLÚ (former VTÚ), and ČKD. ČKD announced it would modify the gearboxes and replace the differential shafts on its own expense, but opinions were divided who should pay the costs for the necessary engine repairs and modifications. ČKD wanted the Ministry to pay for repairs. A proposal to equally share the costs between the Ministry and ČKD was turned down by the VTLÚ, which wanted ČKD to pay for everything. According to ČKD, the heavy wear on the engines was caused by improper handling of the starter engine by the tankers and the usage of oil with too high viscosity. This was disputed by the VTLÚ, whose research pointed out that the engine was not suited for the tank. The production vehicles compared to the initial prototypes had seen their weight increased with 640 kg, which was not compensated with a more powerful and reinforced engine and the material for the cylinder blocks was too soft which caused them to heavily wear down in a short time. They noted that high-quality oil was used in the vehicles and ČKDs accusation of too high viscosity oil usage was incorrect. By 1936, the problems with the starter engines were eliminated when they were modified. The only deficiency after this were the air-filters, the effectiveness of which was found to be unsatisfactory, but due to lack of available room inside the vehicle, other filters could not be fitted. After the military representatives had read the reports, they concluded the faults to be caused by constructional malfunctions and as such, all repair costs had to be paid for by ČKD.

Note on VTÚ and VTLÚ

The Military Technical Institute (Vojenského technického ústavu, shortened to VTÚ) was founded in 1925 and until 1932 based in the barracks at Pohořelec. Per January 1st, 1933, the institute was moved to Dejvice and merged with the Military Aviation Institute (Vojenský letecký ústav studijní, shortened to VLÚS). They went further under the name Military Technical and Aviation Institute (Vojenský technický a letecký ústav, shortened to VTLÚ), hence the name change.

Destined For Export?

In 1934, ČKD tried to export the P-I to other countries, but without success. It is said that conversations were held with Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, China, Estonia, Lithuania, Persia (Iran), Sweden, and Yugoslavia, but to what extent these conversations progressed is unclear, especially in the case of the South-American countries. In January 1935, both Škoda and ČKD received letters from the Iranian purchasing commission in Paris. The Iranian Army wanted to acquire approximately 100 light tanks (2-3 tons class) for which it had contacted manufacturers in other countries as well, including Marmon-Herrington in the US. Škoda offered their S-I tank, ČKD both their AH-IV and TNH. To increase the chance of getting the deal, ČKD donated its P-I prototype to the Persian Shah. If this was a friendly gesture or a blatant bribery is up for debate. Although paid for by the Czech Army, the vehicle was the property of the company and it had no use in the factory anymore. The vehicle raised the Iranian interest for the tanks offered by ČKD. Pleased with the quality of the P-I, by May 14, a deal was secured for 30 AH-IVs and 26 TNHs. After successful trials with the prototypes of these vehicles at the end of 1935, the order was enlarged to 50 tanks of both. To that end, the P-I helped exporting other tanks, but was an export failure in itself. How long the Shah held on to the P-I is unknown, but it was likely scrapped long before 1945.

Service

From 1934 onwards, fifteen tankettes each were assigned to the 1st and 2nd Tankette Companies. Another ten were assigned to the 3rd Light Tank Company, where they were used to train the crews of the LT vz.34 light tanks which had yet to be delivered. The remaining thirty were put in storage and could be activated anytime in case of need. The three prototypes remained with the training unit (Učiliště útočné vozby, shortened to UÚV). With the reorganization of the armored units after September 1935, new units were created including PÚV-1 (Pluk útočné vozby, Assault Vehicles Regiment) in Milovice, PÚV-2 in Vyškov, and PÚV-3 in Martin. Twenty tankettes remained in Milovice with PÚV-1 and were divided over the two companies of the 1st Battalion. A further sixteen went to PÚV-2 in Moravia of which five were stationed in Olomouc, nine in Vyškov and the remaining two in Přáslavice. The thirty tankettes that were previously in storage were attached to PÚV-3 with fourteen in Martin, eight in Bratislava, and eight in Kosice. The last four vehicles were assigned to the training unit in Milovice.

Political Background

When the Czechoslovak state was created in October 1918, not only ethnic Czechs and Slovaks lived within the border, but other ethnic minorities as well, most notably Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, and Poles. Most of the Germans lived in the Sudetenland which roughly encompassed the northern, western, and southern border areas of Czechoslovakia. Although all citizens of the Czechoslovak state had the same rights under their constitution, the minorities still felt disadvantaged, including the Slovaks, as the Czechs were most prominently represented in government. This feeling of mild oppression was especially present with the Germans during the Great Depression as the industrialized Sudetenland was hit the most. This led to a growing demand for economic improvements and local autonomy. This nationalist movement was politically represented by the ‘Sudetendeutsche Partei’ (SdP), founded in 1933 by Konrad Henlein as Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront.

Germany’s Thirst for Czechoslovak Soil

After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, Adolf Hitler found the next territory to be added to the Third Reich, the Sudetenland. He expressed this to Goebbels on March 19. Fueled by German propaganda, the nationalist movement in the Sudetenland became more apparent each day, with the slogan ‘Heim ins Reich’ (back to home) becoming very popular. A military invasion was planned by the German General Staff, known as Operation Green. However, any military action was to be preceded by extensive diplomatic foreplay. The following events eventually lead to the signing of the Munich Agreement by Germany, France, Britain, and Italy. Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union were not consulted. The Agreement called for cession to Germany of the Sudetenland. With the loss of this territory, Czechoslovakia lost most of its industries and defensive lines, as well as a large portion of its population, considerably weakening the country.

The Agreement also directly led to territorial claims from both Poland and Hungary. On October 1, Czechoslovakia accepted ceding the area of Zaolzie to Poland. On November 2, it was followed by the First Vienna Award, which ceded most of Czechoslovak Hungarian-dominated territories to Hungary. The Munich Agreement had also granted autonomy to Slovakia within the Czechoslovak State.

The Tankettes During This Period

With the political situation worsening in 1938, the Czech Army decided to use the tankettes as infantry support, and when the army was partially mobilized during the spring, 23 platoons of three tankettes each were formed which were to strengthen the units on the border of Czechoslovakia. In July, fifteen special emergency units were established directly located in the border areas and to these units, three tankette platoons were assigned, six vehicles from PÚV-1 and three from PÚV-2. During August and September, the army got involved in fighting with members of German nationalists during which the tankettes were involved in combat missions 69 times.

During these missions against the lightly armed insurgents, the vehicles were quite successful in the sense that they provided moral support to the Czechoslovak troops and demoralized the hostile troops. The vehicles did not receive any combat damage, due to the German nationalists lacking any anti-armor capabilities. However, the vehicles often broke down, which meant the platoons went into action with regularly missing one or even two tankettes. After the Munich Agreement was reached on September 30, 1938, the Czechoslovak Army was forced to leave this part of their nation. All tankettes that were deployed in this area were returned to their unit’s headquarters.

At the end of the year, tankettes from PÚV-3 saw some service in Carpathian Ruthenia against Hungarian nationalists, but only on isolated occasions. As such, their action was quite limited. On October 10, an infantry unit, supported by two tankettes, captured members of a Hungarian paramilitary unit (Szabadcsapatok, similar to the German Freikorps). Later that month, both tankettes and light tanks supported an attack on such a unit with the size of roughly a battalion, 300 men were captured. After the first Vienna Award of November 1938, the army had to abandon this area as well.

German occupation

On March 14, the Slovak Republic was created out of the autonomous Slovak part of Czechoslovakia. The next day, on the 15th, German troops occupied Czechoslovakia, meeting virtually no resistance. Concerning the tankettes, the thirty vehicles of PÚV-3 were located in the former Slovak part of Czechoslovakia and were transferred to the Slovak Army. The 43 vehicles located in the former Czech part, were taken over by the German Wehrmacht but what they used them for remains unclear. It is possible that they were used in auxiliary and training units but concrete proof is lacking. Either way, it seems like all of them were scrapped during the war. One vehicle with registration 13.444 was on display at the Army Museum in Munich for some time but this vehicle disappeared as well.

In Slovakia

After Czechoslovakia was split up, a total of thirty vz.33s (registrations 13.460-13.489) ended up with the Slovak Army. A ‘V’ (for vojsko, meaning army) was added in front of the registrations, for example, 13.480 became V-13.480. Some were used as training vehicles for some time, but by the beginning of 1941, all vehicles were put in storage. In January 1944, the Slovak Ministry of Defence assigned the vehicles to the Military Training Command of the State Defense Guard (Veliteľstvu brannej výchovy – Stráže obrany štátu, abbreviated to VBV-SOŠ).

On March 21, 1944, three tankettes were reassigned. V-13.480 to the 1st Engineer Battalion (Pionýrsky prapor), V-13.468 to the 2nd Engineer Battalion and V-13.477 to the 3rd Engineer Battalion. In April, the ministry ordered PÚV to train drivers for 22 vehicles which were to be handed over to VBV-SOŠ, their training was completed on the 25th. The other five remained at the PÚV garages in Martin.

Of the 22 VBV-SOŠ vehicles, five tankettes were assigned to equip the border companies 1 to 5, three to both Automobile Battalion 2 and 11, three remained with PÚV in Martin, three went to a carpark in Trenčín, and five went to the 1st Cavalry Reconnaissance Division in Bratislava. After the outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising in August 1944, several Tančíks saw some use. The uprising was organized by the Slovak resistance movements and aimed to overthrow the collaborationist government and defeat the German occupation forces. The uprising failed and Slovakia was only liberated from Germany in 1945.

At the time of the uprising, ten vehicles were at the Martin barracks, but these were in bad condition and fell in German hands. Several Tančíks were used by partisans at the Tri duby airfield serving as ammunition transporters. The Slovak government had eleven Tančíks to their disposal, of which three were used by German troops. Two were used in fighting against partisans, while a third ended up as a range target at the local garrison. Around seven Tančíks were used by German troops, four of them were used by the 357. Infanterie Division to pull 7.5 cm Pak 40 anti-tank guns, they were still around in 1945. It is said that at least one was used by German troops in its original role, as an infantry support vehicle in Austria. It is presumed that some vehicles that survived in Slovakia up until the end of the war saw some limited use in the post-war Czechoslovak army but to what extent is unclear, maybe just as range targets. Over time, all vehicles disappeared and none are known to have survived.

Conclusion

The Tančik vz.33 sometimes appears in top ten lists of the worst armored fighting vehicles ever and for valid reasons. It was technically unsound and had a low fighting value, resulting in a low tactical value as well. Financially, the vehicle was a burden, both to the Army and ČKD, nevertheless, its development would provide a firm base for ČKD to work from and resulted in the far better AH-IV which became an export success, as well the TNH series of tanks. The vehicle would also prove that it was logistically very favorable to use shared parts with other vehicles, in the case of the Tančik parts commonly used in Praga trucks and cars.

One of the three prototypes of 1933, kept for training recruits. Olive khaki was the standard factory livery between 1933-34.

A regular unit of the borderguard platoons in the summer of 1938. Such units fought against Polish and Hungarian infiltration as well as the Freikorps paramilitary units of Konrad Henlein’s SDP pro-Nazi movement. The three-tone camouflage was the new standard adopted in 1935.

Germany captured forty tankettes when they invaded the Sudetenland. There is no record of any units being equipped with these tanks. They could have been used by some local training units. Here is a prospective example of one of these, in the standard feldgrau paint.

The Slovakian army, allied to the Germans, retained thirty vz.33 tankettes. They were kept for police duties, but records show that, by 1940, most of them were used for training only. However, in September 1944, during the Slovakian insurgency against the Nazis and their local supporters, they had a late opportunity to be used in combat. Here is one of these, fielding the Slovakian cross.

Tančík vz.33 specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 2.7 x 1.75 x 1.45 m (8.86×5.74×4.76 ft) |

| Total weight, battle ready | 2.30 tons |

| Crew | 2 |

| Propulsion | Praga WC 4-cyl, 30hp |

| Speed | 35 km/h (22 mph) |

| Range (road/off road) | 100 km/70 km (62.13/43.5 mi) |

| Armament | 2x Skoda ZB vz.26 7.92 mm (0.31 in) machine-guns |

| Armor | From 6 to 12 mm (0.24-0.47 in) |

| Total production | 74 |

Sources

Československá těžká vojenská technika: Vývoj, výroba, nasazení a export československých tanků, obrněných automobilů a pásových dělostřeleckých tahačů 1918-1956 [Czechoslovak heavy armored vehicles: Development, production, operational use and export of the Czechoslovak tanks, armored cars and tracked artillery tractors 1918-1956], PhDr. Ivo Pejčoch, Charles University Prague, 2009, p.47-53.

Československá obrněná vozidla 1918-48 [Czechoslovak armored vehicles], V. Francev, C.K. Kliment, Praha, 2004.

Export Tankettes Praga, Vladimír Francev, MBI Publications, 2004.

Czechoslovak Fighting Vehicles 1918-1945, H.C. Doyle, C.K. Kliment.

Závady motorů Tančíku VZ.33 [Failure of Tančík VZ.33 engines], Jaroslav Špitálský, Rota Nazdar.

Konstrukce Tančíku VZ.33 [Construction of the Tančík VZ.33], Jaroslav Špitálský, Rota Nazdar.

Zavedení Tančíků do výzbroje [Introduction of tankettes to the Army Equipment], Jaroslav Špitálský, Rota Nazdar.

Tančík vz.33 database on Valka.cz.

Tančík vz.33, Martin Vlach, March 28, 2011, fronta.cz.

VTÚ and VTLÚ on vhu.cz.

Histocialstatistics.org used to convert currency.

One reply on “Tančík vz.33 (P-I)”

This article is very harsh on this vehicle though I do not believe that it is deserving of such reputation. Most of its faults were fixed and tankette became an acceptable vehicle. It served its purpose of cheaply introducing armed forces into realities of armor warfare which even during start of WW2 nations were still learning and making same mistakes as here. This vehicle had served purpose of boosting national economy, gaining industrial capacity, gaining military expertise. In the end, this tankette was not all that much poorer in terms of reliability with most vehicles of that era as they are generally unreliable and lacking characteristics to fulfill its primary functions.