Commonwealth of Australia/United Kingdom (1939)

Commonwealth of Australia/United Kingdom (1939)

AFV – None Built

Budgong Gap may not be the sort of world-famous location associated with great architecture or magnificent structures of the ancient world. Nor is it a place with any association in the world of armored fighting vehicle manufacturers, yet this somewhat obscure location, lying nearly a 3-hour drive south of Sydney, New South Wales in Australia, does have one claim to armored vehicle fame – the Gerreys. World War 2 broke out for Great Britain on 3rd September 1939, when it declared war on Germany after the Wehrmacht had invaded Poland. Australia followed suit, with Prime Minister Robert Menzies announcing that Australia was also once more at war. Within a month, the Gerreys had submitted a design for their own tracked and turreted weapon of war. Looking like a tracked motor car with a turret, the Gerrey design is perhaps yet another of those well-intentioned designs submitted in wartime but is also one of, if not the first of Australia’s homegrown armored vehicle designs of the war.

The Gerreys

The Gerrey family were ranchers/farmers from a very rural part of Australia and had been established in the area from at least the turn of the century.

The two inventive members of this family were Bernard Bowland Gerrey and James Laurence Gerrey. Although it is not known what their relationship was, it is surmised that they were brothers. Both men gave their occupations in Budgong Gap in 1939 as Timber Hauliers. Bernard had previously been in the National Press in 1931, relating of a possible sighting of the wreckage of the Southern Cloud, an Avro 618 which was lost in bad weather in March that year over densely forested wilderness. There would be no fame or reward for Gerrey for that foray into the public eye and the plane was not found until 1958.

The Design

In October 1939, when the Gerreys (both Bernard and James) submitted their design, the vehicle was intended to fulfill a single simple objective – to provide a “motor propelled armoured vehicle” with a turret “in which a series of automatic machine guns are mounted in superposed groups”.

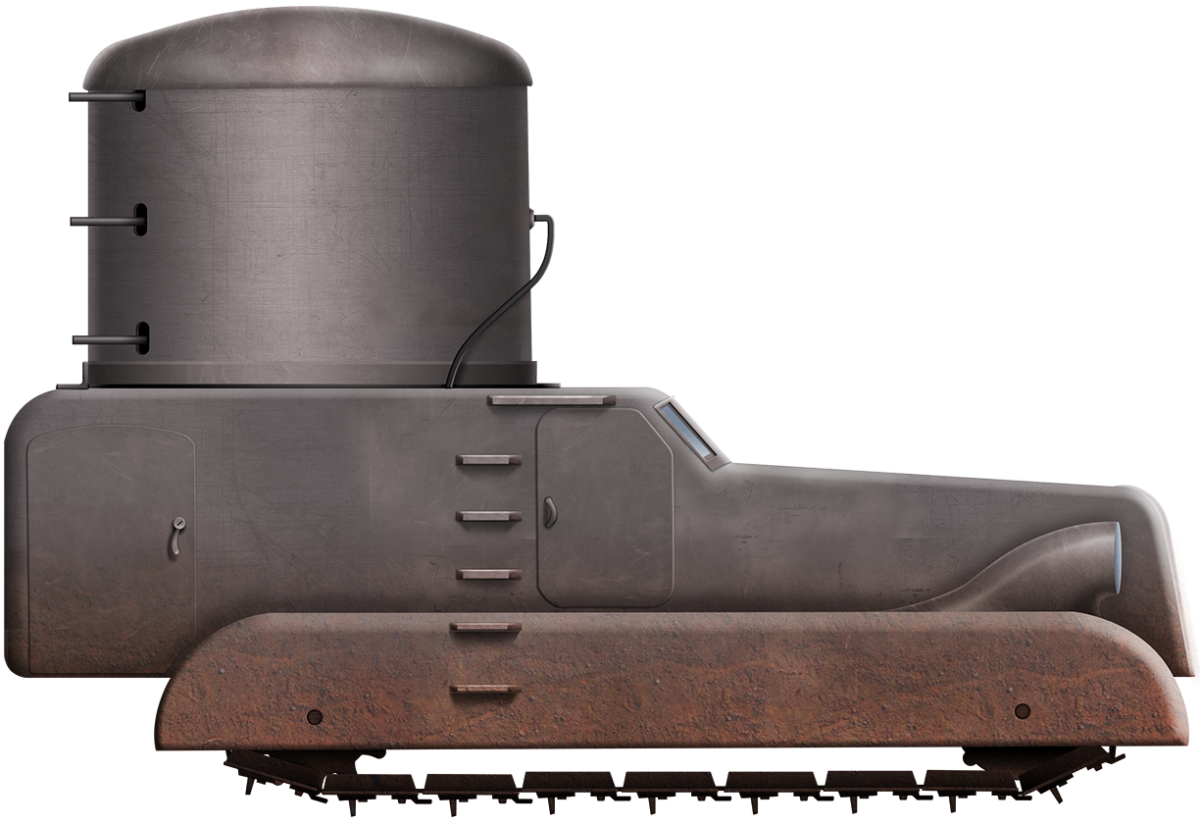

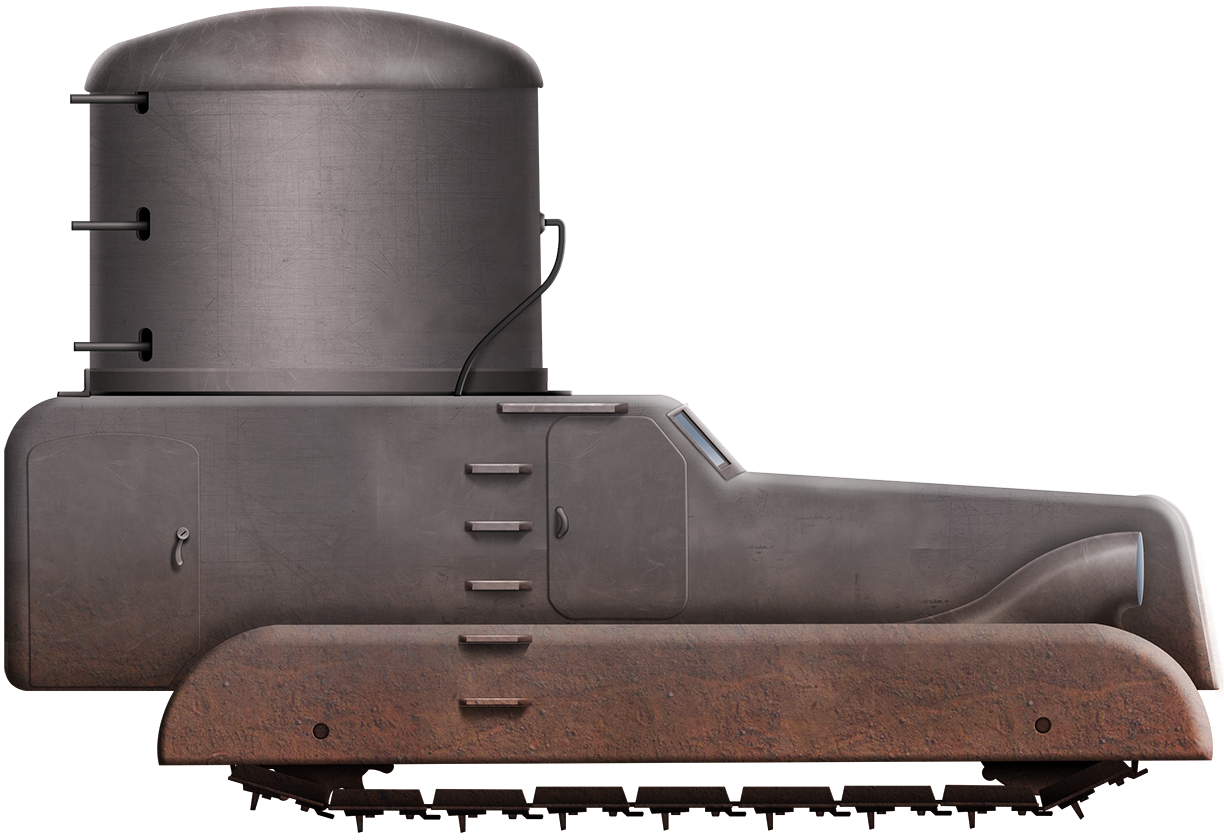

Shaped like a giant boot, the vehicle effectively had the appearance of a tracked saloon car with a giant cylinder sticking up on the back of it. Access to the vehicle was via a pair of large rectangular doors on the right-hand side of the vehicle. The left side is not shown in the drawing, but it can be assumed that these doors were duplicated on the left side as well. The first door was directly accessing the cab area of the ‘car’ part of the vehicle, roughly halfway along the side. The second door was at the back of the vehicle, below the cylindrical turret. Judging from the size of the doors, it would indicate enough space inside for perhaps as many as three men, although a crew of two is perhaps more reasonable as only one man would be needed to drive the vehicle and another to operate the weapons. One final note on access is what appears to be a series of 5 or 6 parallel steps on the right-hand side (and presumably the left as well to match). These steps were on the sides of the vehicle running vertically just behind the door to the driver’s position and running up to the roofline. There appears to be a third hatch shown on the side view just above and behind the side door as well, although it is neither mentioned in the text of the patent application nor in the plan view drawing.

The other very notable feature of the design is the very elegantly sculpted cowls for the pair of headlamps on the wings of the vehicle over the tracks. Such a design feature provided zero military advantages and was clearly inspired by a civilian style of automobile instead.

A crew of two would also match the plan view of the vehicle, which shows just a single opening in the front for the driver and no such opening or weapon on the left of the cab to indicate the need for a second crewman in the ‘car’. Likewise, in the turret, the plan view clearly shows a tractor-style seat for the weapon operator to sit on, indicating just a single man in the turret. At most, therefore, a crew of three could be hypothesized with the third man presumably languishing inside the passenger side of the ‘car’, occupied perhaps with managing a radio.

Both the 1931 report of a possible aircraft sighting and their employment as Timber Hauliers in 1939, as well as the rugged terrain in which they lived, indicate that they should have had at least a working knowledge of vehicles off-road, such as log-hauling tractors. This may account for the flat style of tracks used, as they have the appearance of the type more associated with industrial plant-like crawler tractors and even tracked cranes than the sort of tracks associated with military vehicles, which usually have a well-defined and raised leading front edge for the track.

Indeed, the flat style of track selected is not usually a problem on industrial machines, as the front and back of the bodywork rarely project the way they do on this vehicle. The projection over the back of the vehicle would, for this design, severely limit the steepness of a slope that could be climbed and likewise, at the front, the projecting bodywork would foul on the ground reducing trench crossing ability. This is perhaps the most surprising weakness of the design of the machine from the Gerreys.

Automotive

The ‘car’ shape of the body of the vehicle is misleading, as the means of propulsion is decidedly not-car-like. Instead of running on rubber-tired road wheels, like a normal passenger motor car, this vehicle instead used a pair of full-length and rather narrow tracks. The Gerreys described the means of propulsion for these tracks as consisting of an “internal combustion motor of ordinary type and associated with the usual driving and change speed gear”. However, despite showing the vehicle on tracks, the Gerreys also suggested that this type of turret and armament system could be mounted upon “any kind of transport vehicle”.

The side view available from the patent indicates 20 or so large flat links per track with power delivered via a toothed sprocket located at the back. Each link is overly large for such a small vehicle with a large pitch and would indicate that the vehicle would have serious limitations on its top speed. Likewise, the positioning of the drive sprocket and idler, both in contact with the surface, would create a most uncomfortable ride even if there was any suspension shown or described, which there was not.

The engine, as shown in the plan view, lay at the front, under the bonnet, as would in the case of an ordinary passenger motor car, with the radiator in front of it. In order to protect the radiator from enemy fire, a set of hinged and moveable plates were fitted to the front, which could be opened in order to access the radiator and also allow more air in to improve cooling. Although the lines of the front of the car suggest a bonnet that could be opened in order to access the engine, there is none showed, which would mean a difficult time for anyone trying to do maintenance on the vehicle.

Armament

The primary weapons for the Gerrey design were a series of automatic machine guns. All of them were connected together in the wall of the turret and provided with a slot or other opening through which the barrels could protrude. All of the machine guns could be operated by a single crewman using a simple one-pull trigger, firing all of them at the same time. This wall of fire was no doubt an impressive thought. Assuming perhaps a rate of fire of 600 rounds per minute from each of the unspecified machine guns, it would be essential that each one was fed by a belt, or else the only job of the gunner would be changing magazines. With three rows of machine gun pairs fitted within the large cylindrical turret, a total of at least 6 machine guns (and as much as 18) are shown with their barrels projecting from small loopholes. Six machine guns firing 600 rounds per minute would be 3,600 rounds per minute fired in the general direction of an enemy through a narrow opening, allowing for very limited vertical movement of the guns.

As the vehicle, as drawn, would be using weapons compatible with British supplies, it would suggest weapons like the Browning machine gun and a bullet caliber of .303 or 7.92 mm, like that fired from the BESA machine gun. Belts for the Browning machine gun came in lengths of 500 rounds with two belts to a crate. Assuming the crates or boxes were dispensed off, the weight of the ammunition alone to serve these weapons is a significant burden the Gerreys failed to take into account, as one belt alone weighed in the region of 7 kg. One minute of sustained fire therefore would demand:

((No. of guns x rate of fire) / rounds per belt) x weight of belt

((6 x 600) / 500) x 7 kg = 50 kg of ammunition per minute

That is 50 kg of ammunition per minute, so even a modestly useful combat load of just 10 minutes-worth of fire would mean carrying half a tonne in ammunition alone. For anything other than perhaps anti-aircraft work, the six machine guns were simply adding the weight of the guns, complexity of the mechanism, and weight of the extra ammunition for no particular benefit. Given that the design of the Gerrey vehicle would preclude the anti-aircraft option due to the limited elevation of the guns, it has to be considered that a far more useful and practical arrangement of the firepower from this vehicle would have been served with just a pair of machine guns.

It was, however, these superimposed rows of automatic weapons, all operated by a single person, which was the crux of the patent invention, as they felt that this style of turret was both novel and important. Thus, the Gerreys patented something novel but inherently unusable.

Protection

Few specifics of the armor on the vehicle were described in the patent application, other than to say that the chassis was relatively lightly armored. From this, it can be inferred to be protection against small arms fire rather than the type of protection that would be needed against anti-tank shell fire.

The turret was sat recessed slightly into the body of the vehicle, which would reduce the chances of it being jammed by enemy fire and prevent splash from entering the vehicle through the gap.

Conclusion

The vehicle submitted by the Gerrys was a simple one, well within the technical abilities of the day to produce, but it was also redundant and somewhat naive. Even assuming the engine would have had sufficient power to propel the machine off-road, it was poorly laid out in terms of using space and was therefore going to be heavier than it needed to be. The same is true of the mechanism in the turret – heavily burdened with large gearing more akin to a heavy drive system than one for simply moving and firing machine guns.

They may be excused for some lack of knowledge when it comes to tank design, but it is hard to explain how they might see this vehicle moving across the sort of terrain they would have been familiar with. Overall, the design is crude and relatively poor, showing a great deal of naivety when it came to military vehicle design, with poor use of space and layout. The inherent problems of command and control between the driver and gunner and the excessive multitude of weapons would make any serious operation of the Gerrey vehicle problematic, to say the least, and likely one which would not be able to be operated efficiently under the stresses of combat. Indeed, only the US Army of the era might have been interested in a machine with such a preposterous number of machine guns, but regardless of the military faults, it is the tracks that are the biggest surprise.

For a pair of men who clearly have experience outdoors and almost certainly had seen or used vehicles in that terrain, it is easy to imagine the inspiration for the shape of the tracks they selected. What is less clear, however, is why the overhangs were not identified as a problem.

Nothing became of the design from the Gerreys, which is not really much of a surprise. As skilled as they may have been as timberers or as rugged outback pioneers, their ideas, whilst well-meaning, were simply too naive, too crude, and not fully thought-through – they simply were not what Australia or Britain needed in the war. This design, unofficial as it was, at least started the multitude of ideas coming from Australia for its own armored vehicle programs. Forgotten perhaps almost as soon as it was patented, the vehicle is little more than a short misstep in Australia producing what eventually became a very competent independent tank program. What became of the Gerreys is not clear, but they seem to have dropped their military ideas, submitted no more patents, and likely returned to what they knew best.

Sources

British Patent GB537405, ‘Improvements in Armoured Motor Vehicles provided with Machine Guns’, filed 16th October 1939, granted 20th June 1941.

Kangaroo Valley Voice July 2008: An insight to life back then.

New South Wales Parliament, Proceedings of the Legislative council Votes and Proceedings Volume 6

The Sun (Sydney) 11th July 1931 ‘Southern Cloud Search’

Northern Times (Carnarvon) 16th July 1931 ‘Wreckage of Plane Discovered’

Sidney Morning Herald 25th October 2019 ‘From the Archives, 1958: The Southern Cloud mystery solved after 27 years’