United Kingdom (1951)

United Kingdom (1951)

Light Utility Vehicle – 12,000 Built

An army functions on logistics. Logistics to bring food, men, guns to a fight. Logistics to move around the battlefield, and logistics to get from A to B in peacetime. The vehicle to fulfill these functions must be simple, reliable, rugged, and adaptable. Probably the most famous example of a vehicle to try and meet these needs was the WW2 US ‘Jeep’ but, in post-WW2 Britain, reliance on Jeeps was not going to be adequate. A whole new fleet of vehicles was being developed to prepare the British Army for modern war and replace most of the complex myriad of WW2 vintage equipment which was worn out or simply redundant. As part of this rationalization of the Army, it was desired to have a greater degree of compatibility and capability in the armored and unarmored vehicles than had ever been enjoyed before. These goals led to perhaps the finest light utility vehicle ever to come out of the UK, the appropriately named ‘Champ’.

Development – Gutty and Mudlark to Champ

The post-war desire from the British was to meet the needs for commonality and to generally have a vehicle better than the old Jeep. Work began in 1947 on the ‘Car, 4 x 4, 5 cwt. FV1800 Series’. The name said it all, a car (rather than a truck or armored vehicle), with four-wheel drive in the ¼ ton. (Imperial) class.

The prototype vehicle to meet this need was from Nuffield motors and known as the ‘Gutty’, of which just 2 examples were produced. Powered by a horizontally-opposed 4 cylinder ‘boxer’ engine, this neat vehicle came with deep-bodied sides, simple body panels including a radiator grille stamped from sheet steel with 10 slots (one of the two had vertical slots and the other had horizontal slots), and a curved bonnet with a swell in the top. A flat two-panel folding windscreen, with each panel having its own wiper, provided protection for the occupants from wind or rain whilst driving. A folding canvas tilt was used to cover the occupants from foul weather. Simple folding canvas seats provided some comfort for the occupants.

The Gutty was a sound design, albeit one with room for improvement, and served to spur the Fighting Vehicle and Research Development Establishment (F.V.R.D.E.) to continue development.

Source: Austin-Champ.co.uk

Charles Sewell led the design team, which included Alec (later Sir) Issigonis (most famous for his design of the Austin Mini, amongst others) working on the suspension. It set to work on improving the new vehicle, creating the Mudlark. Thirty prototypes of this new vehicle were constructed by the Wolseley motor car company under contract 6/Veh/2387 signed 27th August 1948. 12 of them were built with a hardtop as a saloon version and another with a 1-ton Turner winch. The power plant for the Mudlark was one of the key successes of the design which would become the Champ. It used a Rolls Royce B40 No. 1 Mk.2A petrol engine. The Mudlark, however, was perhaps a bit too car-like and not Army-like enough, although one Mudlark was shipped to the USA for government evaluation. The body had become more complex than the Gutty, with a more pronounced and rounded bonnet and a small radiator grille with 5 ovaloid holes. The Gutty had relatively simple curved mudguards projecting slightly from the sides, but the Mudlark adopted a large curved mudguard over the front. Whilst this would no doubt have been more effective at stopping mud being thrown up by the front tires when driving off-road, they would also add to the weight, complexity, and cost of the vehicle.

Once more, the design used a flat-bodied design and a folding two-piece windscreen, although the Mudlark was only fitted with a single windscreen wiper for the driver’s side.

Source: Silodrome

Source: David Busfield on Flickr

The Mudlark was simply not adequate to the needs of F.V.R.D.E., which now had fully adopted the idea of commonality of engine parts. Tests of the Mudlark found problems with oil leaking from the differentials into the wheel hubs and it was clear that the Mudlark needed some additional improvement.

Twelve pre-production Champs were made for evaluation, with half as the Cargo version and half as the Fitted For Wireless (FFW) model. These vehicles tested very well in trials and little was needed for this vehicle to be put into production, although the most distinctive change would be the addition of pioneer tools to the outside and a more refined dashboard.

The ‘Car, 4 x 4, 5 cwt. FV1800 Series’ became the ‘Truck ¼ ton, 4 x 4 CT’, indicating it was now going to be more than just a car, but was still going to be capable of four-wheel drive and in the same weight class. However, now, by virtue of the ‘CT’ designation, it was suitable for use in a combat theatre, although CT stands simply for the first and last letters of the word combat rather than as an abbreviation for something specific. It retained the FV1800 series designation. This truck would fill the bottom end of the logistics spectrum compared to its larger siblings, the ‘Truck, 1 ton, 4 x 4,CT’ made by Humber motors, and the ‘Truck, 10 ton, 6 x 6, CT’ made by Leyland as the Layland Martian. Humber and Leyland had both hoped for the production contracts for the Champ, but it was Austin that got it.

Thus, the first of a new breed of light trucks had been born, and contract 6/Veh/5531 was signed for 15,000 vehicles for the Army. Production began on 1st September 1951 by Austin out of their plant at Cofton Hackett near Birmingham as the ‘FV1801A, Truck, ¼ ton, 4 x 4, CT, Austin Mk.1’ in both Cargo and FFW versions. The vehicle for the Army retained that rather complex name, whilst the version available on the civilian market was ‘Champ’. This was quickly adopted by the Army as well and, therefore, from its origins onwards, the vehicle would simply be known as Champ.

Construction

The Champ used a solidly built bodywork made from pressed steel panels from the ‘Pressed Steel Company’. These were welded together on top of an ‘X’ shaped chassis. The bodywork added stiffness to the design with reinforcing ribs pressed into the bodywork to increase integrity. The rear wheel arches were simple curves pressed out of the body, but the front ones were simple pressed extensions from the front, with a horizontal portion at the top turning to a down-angle – no more curves or flared wheel arches like on the Mudlark. The bonnet and grille, however, showed its Mudlark heritage much better, with a 5 ovaloid opening radiator and large rounded bonnet.

The two-panel windscreen, like the Gutty and Mudlark before it, could be folded down over the bonnet and was fitted with a pair of windscreen wipers.

A folding tilt, made from PVC-coated cloth rather than waterproof canvas, kept out the weather without the weight of a canvas title and featured a small vertical plastic window ahead of the door, a larger window in the door, and a pair of triangular windows in the rear. The doors and side panels were separately removable, allowing for the vehicle to operate simply with a title covering the top and rear but totally open sides (apart from the ‘V’-shaped struts holding the roof up) on each side.

On the rear of the Champ, a fitting for a spare Dunlop 6.5 or 7.5 x 16 tire came as standard on the rear right, and a jerry can on the rear left.

Automotives

The 80 bhp 2.838 liter Rolls Royce B40 petrol engine was a solidly built and rugged design. With 4 cylinders (‘40’ means 4 cylinders in the series designation) and a bore of 3.5”, this was a tough and solidly built motor using a carburetor (No. 1 was a carburetor engine in the series designation), cast-iron block, and a cast aluminum cylinder head. The engine had started life in 1936 to make an engine as reliable as could be.

Originally manufactured by Rolls Royce in Crewe, early production vehicles used the same No.1 Mk.2A version of the B40 which still had British Standard Fine (BSF) threads, even though, in 1949, a production switch had been made to use Unified Fine Thread (UNF) as the Mk.5 engine. Later production engines, therefore, moved from that Mk.2A version for the first 30 prototypes to the 2A/4 model for the next 1,477 vehicles, followed by the Mk.5A for the remainder. Some Mk.5 engine production was carried out by Austin Motors under license as the ‘Austin-Rolls’, with some simplifications added in. One of these was a switch from an aluminum cylinder head to a cast-iron one.

Civilian sales of the Champ were not a success, primarily because it was expensive, but the engine was also different. The civilian market Champ was sold with either the Rolls Royce B40 or the more economical 2.66-liter Austin A90 petrol engine. It would also not be sold waterproofed.

On the military version, the engine, along with all of the electrical systems, like the ignition and also the transmission, were completely sealed. This meant that the Champ was waterproof, with the engine perfectly able to run even when completely submerged. Video footage of the vehicle taken in the deep wading tank at Chertsey shows this very well, with the only thing required to wade being the erection of the deep wading air intake on the front right of the bonnet. The driver could then simply stand up to keep his head out of the water and then drive the Champ through water up to 6’ (1.8 m) deep. As long as the air intake was out of the water, the Champ was perfectly able to wade through any depth, although the real limitations of its wading were down to the height of the driver more than anything technical on the vehicle.

In the freshwater deep wading tank at Farnborough, 19th November 1952. The driver has sensibly prepared for immersion. The snorkel is up and the Champ will show its waterproofing to the full. Source: David Busfield on Flickr

The transmission system for the Champ was a robust 5-speed box with synchromesh connected to a Borg and Beck clutch. This made for a simple and robust system, to which a drive shaft was connected running under the truck to the transfer box at the back and thence to the rear wheels. The reversing gearing for the Champ was located in the transfer box at the back, which, in effect, meant that the Champ could go backward at the same speed it could go forwards, although it is unclear who, if anyone, ever tried reversing one at 50 mph (80.5 km/h). The feature of high-speed reverse, whilst hazardous for ‘normal’ use, would have an advantage for the vehicle if it was being used as a weapons carrier or for reconnaissance, where going backward very quickly out of sight of an enemy might be an advantage. One extra thing included on the civilian model was a Power Take-Off (PTO) on the transfer box, as it would be more useful for civilian farm-related tasks.

The suspension for the Champ, designed by Issigonis, used fully independent double wishbones on the front and rear, with torsion bars running underneath down the middle of the vehicle connected to the central meeting point of the ‘X’-shaped frame on which the vehicle was built. This unusual system provided for a superb level of comfort even off-road.

The Champ operated on a 24-volt electrical system allowing for easy fitting of radio equipment to form an FFW (Fitted For Wireless) vehicle, with just the addition of a sliding table and battery mounts. Civilian versions of the Champ operated on a more conventional and simpler 12-volt electrical system.

Operating on a 20 gallon (90.9 litres) petrol tank, this provided the Champ with an operational range of around 300 miles (483 km) at 15 mpg (6.4 km/l), although off-road or harsh driving, or being fully laden, would reduce that number substantially.

Versions

As part of FV1800 series vehicles, there were sub-designations of the Champ in service. Specifically:

FV1801A – Basic cargo version for use by all arms

FV1801A/1 – Basic FFW (Fitted For Wireless) vehicle

FV1801A/2 – Ambulance with modified body

FV1801A/3 – Cable layer for signals use with rear-mounted drum

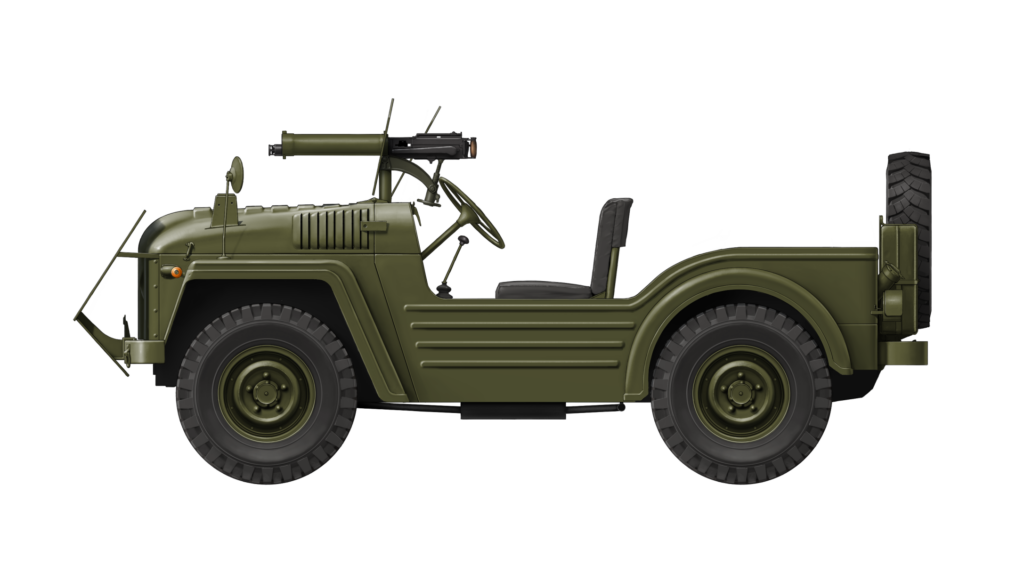

FV1801A/4 – 0.5” heavy machine gun mount (unarmored) – no windscreen fitted

FV1801A/5 – 0.303 Vickers machine gun mount (armored)

Weapons

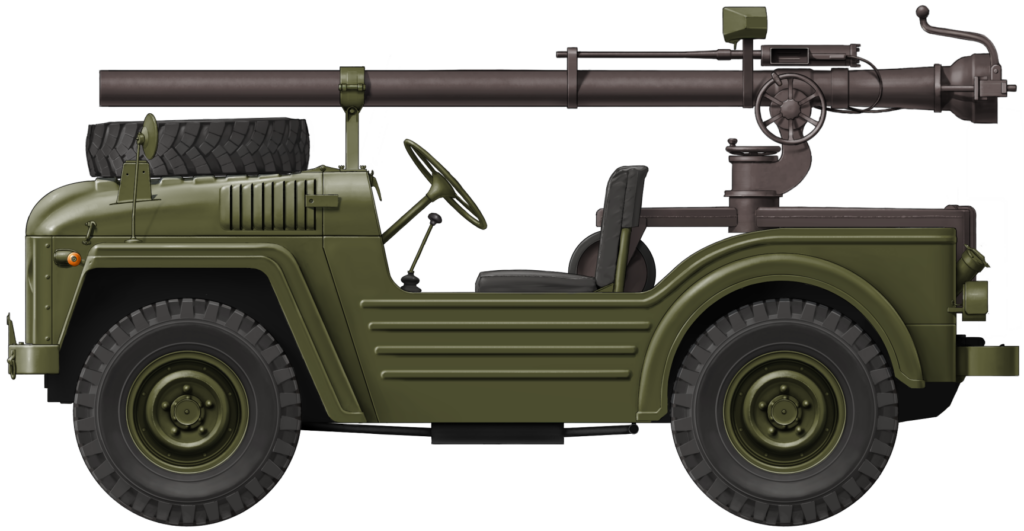

The standard general service Champ was not armed but, like the Jeep before it, could be adapted to carry a variety of weapons for whatever task it might be called upon to fulfill. Weapons carried on various mounts included the .303 caliber Bren light machine gun, .303 Vickers machine gun, 7.62 mm Browning machine gun, a 106 mm recoilless rifle, and even a 3” mortar.

Introduced to the British airborne force in 1956, the 106 mm recoilless rifle, in particular, offered a valuable capability for them, specifically the ability to bring a weapon capable of defeating any known tank at the time on an airborne operation on a mobile platform. This weapon, the M40, was actually 105 mm in caliber, but classed and named as 106 mm to avoid confusion with 105 mm tank ammunition. Loaded with a single shell at the time via a folding breech, it could fire a high explosive anti-tank round capable of defeating up to 400 mm of armor to a maximum range of just under 7 km. With a .50 caliber spotting rifle attached to improve accuracy, the weapon proved its value in Suez 1956, when one was used to knock out a Soviet SU-100 belonging to Egyptian forces.

A Weapon’s Mount that is not

A Champ used in a short TV film from British comedy duo Morecambe and Wise featured a Vickers water-cooled machine gun mounted inside the passenger space. This was not the correct mounting point for the weapon and only seems to have appeared because of the show itself. The Vickers machine gun mount was carried, in the normal position, on the front left of the vehicle and, therefore, would not have to fire over or through the driver to get to the target. The correct positioning of the Vickers machine gun can be seen in the section titled ‘Armor’.

Source: Austin-Champ.co.uk

Armor

Fifty sets of armor plates were produced for the Champ as part of trials for the FV1801A/5 version. Each kit cost GBP£100 (GBP£3,200 in 2020 values) and they were trialed prior to 1959, as they were disposed of from stores starting in 1958. The armor protection was modest. A large single angled plate was mounted on the front, covering the vulnerable radiator extending just above the bonnet, and would deflect bullets upwards over the vehicle or down in the ground. For the men crewing the vehicle, two rectangular shields were provided, with one for the driver and another for the front seat passenger featuring a cut out for a .303 caliber Vickers water-cooled machine gun. Less clear at first glance is what appears to be a semi-circular armor plate riveted over the dashboard bulkhead. Presumably, a cut-out was provided for the dials so the crew could see the speed of the vehicle, but this additional protection would prevent shots that avoided the front deflector plate from injuring the crew by simply passing through the top of the vehicle above the bonnet. No side, rear, or roof armor protection was provided and the arrangement was clearly set out with a reconnaissance version in mind. The total weight of the armor is unclear, but it was not extensive, so it is unlikely to have affected the performance outside of making it harder for the driver to see where he was going. The thickness of the armor is also unknown, but to be of use ballistically, it would likely be 8 to 10 mm thick.

The high mounting position of the machine gun is also of note. Positioned as it was, the front seat passenger would clearly be able to operate the gun from a seated position, firing forwards with complete coverage for their head from the plating. This would not be the most accurate way of firing, as aiming would be very difficult. If accurate firing was needed, the operator could simply stand up and still have their torso behind the plate.

Service

The regular British Army got the Champ just too late for the war in Korea, but in time for the intervention in Suez in 1956. It was also issued to units in Germany with the British Army of the Rhine (B.A.O.R.), Far East Land Forces (F.E.L.F.) in Hong Kong, Malaya, and Singapore as well as units with Middle East Land Forces (M.E.L.F.) in places such as Cyprus, Egypt, Aden, Malta, and Libya. Other vehicles went to British Guiana and Caribbean Command (C.C.) in Jamaica as well as East Africa Command (E.A.C.) in Kenya and Uganda. Basically, everywhere the Army of the era would be stationed, one could expect a Champ to make an appearance.

The British Army was not the only user either. In 1953, 400 brand new Champs were also purchased by the Australian Army from the British Ministry of Supply. They wanted these as a supplement rather than as a replacement to the Jeep. This was followed by the purchase of another 400 used vehicles from British Army stocks. Two other Champs fitted with the Austin A90 engine instead of the Rolls Royce B40 were trialed in Australia but returned after testing. Like the British, who had fitted a recoilless rifle to theirs, one Australian vehicle was also fitted with an M401A1 106 mm rifle, but only on an experimental basis. All of the Australian vehicles were withdrawn from service in the mid-1960s.

The French Army also trialed a cargo version of the Champ in 1953, fitted with a one-ton winch. That Champ was tested by loading it with 400 kg of ballast and driving across various terrain. The Champ passed the French trials very well and performed better off-road than the French Delahaye VLR, but was eventually rejected in preference for the French vehicle.

The End

Automotively, the vehicle was excellent. It had good performance, great riding characteristics, was solidly built, and had a rugged and reliable engine with lots of commonality with other vehicles for a low logistic burden to support it. With that, it might be surmised that the vehicle was a success, but it was not. It was prone to misuse and abuse, being fun to drive off-road, which caused some issues with broken rear axles. The primary problem, just as it had been with the Mudlark, was a lack of attention to oil levels in the axles. The overly complex electrical system and other features also proved hard to service and the benefit of spares interchangeability across other vehicles proved to be less useful than it might have been.

Despite this, the vehicle was popular, comfortable, and fitted with a heater. This was guaranteed to win the hearts of many soldiers but all of these were side issues to the real problem. The Champ was a bit too good. It just cost too much and did more than the Army really needed. The designers had gone too far and really built the Rolls Royce of Jeeps when what was needed was more a Toyota of Jeeps, reliable, but at a better price. The Champ cost a whopping GBP£1,200 (GBP£35,500 in 2020 values) per vehicle. With some 15,000 on order, this meant a huge cost that post-war Britain could little afford to spend on gold-plated vehicles. With the arrival of a cost-effective alternative in the form of the Land Rover from Rover Motor Cars, at nearly half the price and nearly all the capability, the Champ was doomed. In 1955, with 11,732 built, production ended and the 86” wheelbase Land Rovers began to replace the Champ in regular army service as ‘Truck, ¼ ton, 4 x 4, GS, Rover Mk.3’. Around 500 of the civilian version of the Champ were also made.

As they were being phased out through the 1960s, the Champs were pushed through Territorial Army units before the final vehicles were sold off in 1968.

Source: ousewashes.info

The Champ had proved a mixed blessing. It was more capable than the WW2-era Jeep, but it was complex and expensive. Soldiers did not enjoy the additional maintenance burden of looking after the Champ. Many road accidents which had occurred during its service gave rise to an impression of it being top-heavy or having a tendency to roll, although this was more to do with improper training or soldiers who were too used to the poor suspension on the Jeep, misjudging corners.

Survivors

Today, the Austin Champ remains a popular vehicle with military vehicle enthusiasts. Two of the pre-production vehicles were known to have survived into the 1970s, although they are currently of unknown status. One of the two Guttys produced survived at the Heritage Motor Centre in Gayden, Warwickshire. Two surviving Mudlarks are known, with one believed to be in the USA. Two of the 50 Champs built as armored versions still survive, with one in the USA, although neither is fitted with the original armor.

Austin Champ specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 12’ (3.66 m) long, 5’ (1.65 m) wide, 6’ 8.5” (1.87 m) high with tilt erected |

| Crew | 1 (Driver), seating for 5 |

| Propulsion | Rolls Royce B40 2.838 liter petrol engine producing 80 bhp at 3,750 rpm, or Austin A90 2.66 liter petrol |

| Speed (road) | 50 mph (80.5 km/h) |

| Armament | None but optionally fitted with machine guns or a recoilless rifle |

| Armor | None as standard but armor kits available est. 8 – 10 mm thick |

| For information about abbreviations check the Lexical Index | |

Sources

Austin Champ.co.uk

Cecil, M. Champ or Chump: The FV1801 Austin Champ in Australian Service. Army Motors.

Hover Train (Tracked Hovercraft) Experiments, Earth-Sutton Gault. At http://www.ousewashes.info/experiments/hovertrain.htm

Mastrangelo, J. (2008). A Brief History of the Austin Champ

Paradate.org.uk

Remlr.com: Austin Champ

Silodrome Gasoline Culture

6 replies on “FV1801A Austin Champ”

How much did the Austin Champ weigh? also were the seats changed from the Mudlark or did the Champ use the same seats as the Mudlark?

Thanks for your detailed article on the Champ. I learned a lot of new stuff. I had one from 1968-72 and drove from England to Central Turkey to start a job there. Brilliant is the word I use to describe it. Performed without any issues in all terrains including an ascent of Mt Erciyes, elevation 3916 meters, in winter, pushing bonnet-high snow the whole way up. Wish I still had one!

I am working on a 1/72 scale new kit master of the Austin Champ and have a couple of questions:

Did the RAF, Royal Marines or Royal Navy every use the Champ?

Was it only sold to Australia?

Does anyone have good quality images of the Champ in army service (colour photos)

Hi, Enjoyed the read and learnt some more. I have a civilian one in NZ. It has been good although needs TLC now.

Thanks for the article.

1. The engine number of my champ is 5186.

2. The number on the body is 9688

Can you determine the year model of the Champ?

Hi Frank. I look after the Champ Register for the Owners’ Club. If the engine number is correct and complete, it was not fitted to any production Champ and will therefore be a crated unit probably fitted in civilian life. Is the number 9688 stamped on the the bulkhead plates (i.e. the actual chassis number)? There is also a number stamped on the front chassis legs but that is not the chassis number. If you could confirm by email that 9688 is the chassis number, I can give you further information. Regards Ian