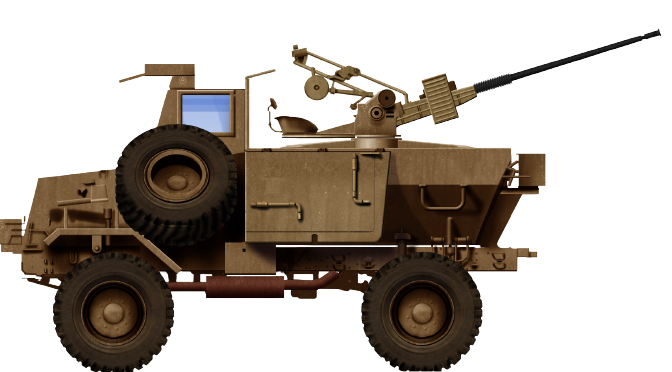

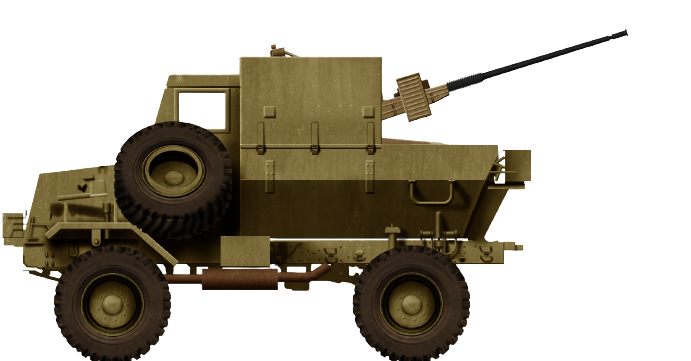

Republic of South Africa (1984)

Republic of South Africa (1984)

Self-Propelled Anti-Aircraft Gun – ~70 Built

“Ystervark” The African Porcupine

The Ystervark takes its Afrikaans name from the South African or ‘Cape’ porcupine. The world’s largest porcupines and an animal with a strong body and protected by an impressive array of spines to defend itself against predators a vehicle named for this animal should embody those characteristics. The Ystervark self-propelled anti-aircraft gun (SPAAG) is exactly that, a sturdy and robust vehicle evolved to suit the harsh Southern African environment.

Development

In 1983/84, the South African Defence Force (SADF) Anti-Aircraft Regiments had to tow their anti-aircraft artillery which consisted mainly of GAI-CO1 20 mm AA guns. With the SADFs transition to mobile warfare, towing was no longer suitable. The first mobile anti-aircraft vehicle incarnation came into being in 1983/84 as the brainchild of Johan Craft. It consisted of a Mercedes Benz gun tractor on which three wooden railway sleepers fitted with bolts and blue wire to mount the gas-operated GAI-CO1 20 mm anti-aircraft gun. From these testbeds, the vehicle operational requirement was developed and tested, and requirements for further development were given to Armaments Corporation of South Africa (ARMSCOR), which included the need for a mine-resistant chassis. The latter testbeds were relegated to a training role.

In 1981, before the need for a mine-resistant light anti-aircraft capability had been decided, Project Sireb had been launched. This project produced three mine-resistant vehicles as possible replacements for the Buffel APC. These prototypes were based on the SAMIL 20 chassis and were fitted with a full-length mine-protected hull which had a much higher and beefier suspension than the basic SAMIL 20 truck, leading to better cross-country performance. Unfortunately, none of the prototypes was found to be significantly better than the Buffel and further work was needed. However, one of the prototypes, known as the ‘Bulldog’, was adopted by the SAAF as an APC for use in airfield patrols. The Bulldog would form the basis on which the Ystervark would be built, by removing the passenger tub and replacing it with a weapons deck.

The Ystervark was developed from the requirements for a mobile self-propelled and mine-protected vehicle to provide a light anti-aircraft capability and which could accompany South African mechanized battalions on combat operations. The Ystervark was also employed to protect strategic assets, such as air bases in South-West Africa (SWA).

During Operation Thunder Chariot (1984), which was a division-sized exercise in South Africa, four Ystervarks were used operationally for the first time for evaluation.

The Ystervark’s first combat use was as part of 32 Battalion (32Bn) in 1986. Its continued presence with SADF mechanized battalions during Operations Modular, Hooper, and Excite in Angola provided a sufficient deterrent against Angolan and Cuban piloted MiGs, who seldom flew very low and preferred to remain at high altitudes.

On 8th October 1987, one of two MiG 23 aircraft bombing the 61 Mechanized Battalion Group (Meg Bn) laager with 500 kg bombs was shot down by 32Bn Ystervark when it pulled up at its end bombing run.

On 17th March 1988, Cuban pilot Ernesto Chavez, flying a MiG 23, was shot down and killed by a Ystervark while flying over Cuito Cuanavale.

The SADF deployed the Ystervark with the permanent forces at 101 Battery and 10 Anti-Aircraft Regiment. With the conclusion of the Border War, the Ystervark was phased out in 1991 and replaced with the SAMIL 100 Kwêvoël mine-protected SPAA truck called the Bosvark. This was armed with a twin 23 mm gun. The Ystervark was officially withdrawn from service in 1997.

It is unclear how many Ystervarks were produced although, it is estimated that at least 70. The Ystervark was only employed by the SADF.

Design features

The Ystervark was designed to maximize its crews` chances of survival when a mine was detonated anywhere under the hull. This was achieved through several key design elements, which included high ground clearance, a V-shaped underbelly, and a purpose-built strengthened upper design which reduced the risk of shattered or buckled hull plates that could become debris.

The African terrain, which in and of itself can inflict severe punishment on a vehicle, necessitates a robust design. The Ystervark’s design and simplicity made field repairs post-mine detonation possible, although very costly. A chassis-based MPV does not provide the same protection to the vehicle driveline when compared to modern monocoque hull design vehicles. Most parts could be obtained commercially, which made the Ystervarks logistical train shorter and specialized maintenance support in the field unnecessary

Mobility

The SAMIL 20 chassis was designed for difficult off-road applications in Africa. The suspension consisted of single-leaf springs on the front axle and double coil springs on the rear axle. The Ystervark had a ground clearance of 460 mm (18.1 in) and could ford 1.2 m (3.9 ft) of water. The Type F6L 913 air-cooled 4 stroke Deutz6 cylinder with direct injection engine produced 124 hp (20.4 hp/t) at 2,650 rpm and was coupled to a five-speed (four forward and one reverse) synchromesh manual transmission consisting of a two-shaft z-65 drive via a transfer case with pneumatically lockable planetary differential gear. The vehicle had permanent 4 × 4 wheel drive. The four wheels were 14.50×20 in size. The Ystervark could cross a 0.85 m (33 in.) ditch at a crawl. The front and rear axle consisted of a portal driving axle with a pneumatically lockable differential with a portal spur gear set.

Endurance and logistics

The Ystervark had a 200 l (52.8 US gal.) fuel tank which granted it an operational range of 950 km (590 mi.) on-road and 475 km (295 mi.) off-road. Its maximum road speed was 90 km/h (55 mph) and 30 km/h (19 mph) off-road. A modular design allowed for easier maintenance and reduced logistical requirements. Additionally, the domestic production of components made replacement easy and lowered the cost for parts. A 100 l (26.4 US gal.) freshwater tank was located inside the V-shaped hull for the crew and was accessible via a tap located at the rear left of the lower vehicle’s V-shape.

Vehicle layout

The Ystervark consisted of three main parts: chassis, armored driver’s cab at the front right of the vehicle, and the weapons deck at the center rear, where the main armament was mounted. The engine was located at the center front of the vehicle and the transmission in-between the engine and the armored driver’s cab. The engine and transmission placement facilitated easy replacement in the event of damage due to a mine detonation.

The driver’s cab was surrounded by three rectangular bulletproof glass windows and had an unarmored high-density polyethylene roof cover. The base was wedge-shaped and secured to the chassis. A single door was installed on the right side of the driver’s cab, as well as two steel steps for ease of entrance. The gear selector stick was located on the driver’s left-hand side, and a spare wheel was kept to the left of the driver’s cab. The crew seating was blast-resistant and designed to protect the spine in case of a mine detonation under the vehicle.

Access to the weapons deck was gained via two incremental pairs of steel steps on either side, above the rear wheels. The weapon deck seating consisted of two seats in between the driver’s cab and weapons deck, each facing towards the rear of the vehicle. The crew commander sat on the seat directly behind the driver’s cab to facilitate communication with the driver through an opening at the rear of the driver’s cab. The gunner sat on the right-hand seat of the weapons deck. Both seats were equipped with harnesses to secure the crew in case of a mine detonation or accidental rollover. The middle of the left and right sides of the weapons deck contained horizontal hinged panels which could be opened outward via quick release when the main armament was to be used. The left and right panels could fold down all the way, while the middle-left panel only dropped down 45 degrees. While crossing uneven terrain at speed, the panels were secured in their upright position.

On the rear of the weapons, the deck was a sizable storage box manufactured from high-density polyethylene. The front lower part of the storage box was used by the passengers to store the spare kit, while the top part was for the driver’s use. At the rear of the V-shape was a water tap that was connected to a 100 l (26.4 US gal.) freshwater tank located within the V-shape. For tactical communication, an A-53 (UHF) man-portable radio set was kept at the front of the weapons deck, between the commander and gunner seats.

Protection

The Ystervark could protect its crew against a single TM-57 anti-tank mine blast under the hull, which was equivalent to 6.34 kg (14 lb.) of TNT, or a double TM-57 anti-tank mine blast under any wheel. Its V-shaped bottom armored hull design deflected blast energy and fragments away from the driver and weapons deck. Plastic fuel and freshwater tanks were located within the V-shaped hull of the weapons deck. These tanks would help absorb explosive blast energy from a mine detonation.

The driver’s cab windows were all bulletproof. The armored driver’s cab and weapons deck side panels were at least 7 mm (0.27 in) thick, offering protection against common small arms fire in the Angolan theatre. These included 7.62 mm NATO and 7.62 mm AK-47 Ball ammunition, as well as explosive fragments. However, the rear of the weapons deck, as well as the top, were exposed.

Firepower

The Ystervark`s main armament weighing in at 512 kg was a gas-operated GAI-CO1 20 mm anti-aircraft gun fitted to the weapons deck on three legs, two facing backward and one to the front. The GAI-C01 made use of a KAD-B13-3 cannon which fired from a single feed 75-round magazine from the right-hand side. The rate of fire was 550 rounds/min, which translated into nine one-second bursts before reloading was required. Available ammunition included APHE, HE, and tracer. The HE ammunition weighed 125 g and had a muzzle velocity of 1100 m/s, while the AP, weighing 110 g, had a muzzle velocity of 1050 m/s. The ammunition had an effective range of 2,000 m and the APHE could penetrate 15 mm of RHA at zero degrees at 800 m. The ammunition performance was more than adequate against low-flying aircraft, helicopters, and soft and lightly armored vehicles. A typical ammunition belt consisted of five or seven rounds of HE followed by an APHE one.

The elevation was achieved with a handwheel and traverse with pumping pedals, making it somewhat limited in engaging fast-moving targets. The gun could elevate between -7 to +83 degrees and could traverse 360 degrees. The full range of elevation was, however, limited to some 270 degrees, as the driver’s cab is in the way.

Ammunition storage was limited to three bins located on the floor of the weapons deck, each of which housed two 75 round magazines (450 rounds total). During operations, this was increased to nine 75 round magazines (675 rounds total). The Ystervark primarily relied on resupply from a Kwêvoël-100 ammunition vehicle for sustained combat operations.

Fire Control System

The mount traditionally included an x1 sight for antiaircraft use and an x3.7 sight for ground targets. The Ystervark’s main armament was fitted with a Delta IV reflector sight which could be set for targets with speeds between 200 km/h and 900 km/h and could be illuminated at night.

Operational Use

Operational Doctrine

“In Sept 1986, the Officer Commanding of 61 Meg Bn Gp, Kmdt K. Smith tasked the Foxtrot Bty Cmdr, Capt Deon Bornman to as a matter of priority formulate and practice the operational and tactical doctrine for the Ystervark to integrate and operate within in Mechanized Columns. The initial ideas were soundly based on the 61 Meg Bn Gp SOP. The concept of movement and manoeuvring with the mechanised forces was tested successfully in exercises that year. This became the new norm of Mobile AA in 1987. The era of AA protecting Echelon’s and static targets ended! This then became the standard operating procedure (SOP) for applying the Ystervark with mechanised units. The doctrine was introduced to the AA School and 101 Bty, 10 AA Regiment in 1989 and the official AA Battle Handling doctrine was updated.

The Ystervark units moved along with their assigned mechanised battalions, either one tactical jump (100-200 m) behind the A Echelon or on the flanks of the force. As per enemy appreciation and the typical formations of own attacking forces, it was envisaged that an enemy air attacked will definitely come from the flank. The Ystervark could not practice fire and movement, as their main armament faced backwards and needed to be stationary to fire. This was a limitation but not a deterrent for operational deployment. Typical target protection was advancing columns and the protection of vital assets, such as headquarters, laagers and harbours, artillery, supplies or medical vehicles. The main advantage of the vehicle that it was in 100% of cases in operations ready to move and/or redeploy with 10 minutes made the system adaptable and efficient as a deterrent.

Only on one occasion, in September 1987, was the Ystervark used in a conventional role during the ‘advance to contact’ with 61 Mech, when they due to the lack of enemy aircraft successfully attacked the People’s Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) 47 Brigade ground forces. The Ystervark effectively engaged the visible vehicles, soft targets and infantry while protecting the flanks of the mechanized force.”

Former Foxtrot Bty Cmdr, Capt D. Bornman

A lack of armor protection necessitated extreme proficiency with camouflage as a passive defense. The Ystervark’s success lay in its presence as a deterrent, which resulted in very few enemy MiG sorties at treetop level. Those who did venture low were engaged.

Conclusion