Czechoslovakia/Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1936)

Czechoslovakia/Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1936)

Tankette – 8 Purchased

In an effort to equip its cavalry divisions with armored vehicles, the Yugoslav Royal Army began a series of negotiations with several European nations. While for a variety of reasons almost all would end up unrealized, one would, to some extent, be successful. After a number of examinations and testing of various armored vehicles, finally, in 1936, a deal was made with the Czechoslovakian weapon manufacturer Škoda for the acquisition of 8 Š-I-d tankettes. These were delivered in August 1937 and remained in service up to 1941.

Need for Modernization

During the 1930s, armies in Europe, such as France, for example, were slowly modernizing their cavalry units by attaching various mechanized elements to increase their speed and combat effectiveness. Horses were being replaced with trucks that could transport soldiers, weapons, and supplies. To increase the offensive capabilities of these new mechanized units, armored vehicles, such as tanks and armored cars, were being attached to them.

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s neighbors also initiated such reorganizations of their cavalry units to some extent. Not wanting to be left behind in this arms race, the Yugoslav Royal Army decided to implement a similar reorganization of its own cavalry divisions. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia originally had only two cavalry divisions, one formed after the First World War, and the second in 1921. These would be supplemented by the cavalry brigade which was attached to the Royal King’s Guard unit. In 1930, a bicycle battalion was also attached to each cavalry division. More serious steps in the motorization of these two divisions were initiated by General Milan Nedić in 1934. It was planned to attach a motorized regiment to each division. However, it was necessary to obtain some light tanks or tankettes for these cavalry units.

The Yugoslav Royal Army had fewer than 60 Renault FTs and its modified M-28 counterpart available in its inventory. Given the obsolescence and poor speed of available FT tanks, another vehicle was necessary to fulfill this role. This was not as easy a task as it seems at first glance. Europe at that time was getting deeper into a political fracture between the Western Allies and Germany. Countries that had a good relationship with Yugoslavia, such as France, wanted to dispose of their older surplus models first, keeping the new models for themselves in case of war with Germany. These older designs were not appealing to the Yugoslav Royal Army officials, so they turned to other potential candidates. These included Poland, Czechoslovakia, and even the Soviet Union.

Search For A Proper Solution

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Poland had relatively good military cooperation, with the acquisition of different military equipment and weapons. In 1932, Poland and the Yugoslav Royal Army signed an agreement for the purchase of some 14 Polish Renault FT tanks. A year later, one TK-3 tankette was tested to see if it satisfied the Royal Yugoslav Army’s requirements. While not much is known about these trials, it appears it was not successful, as no contract was ever signed.

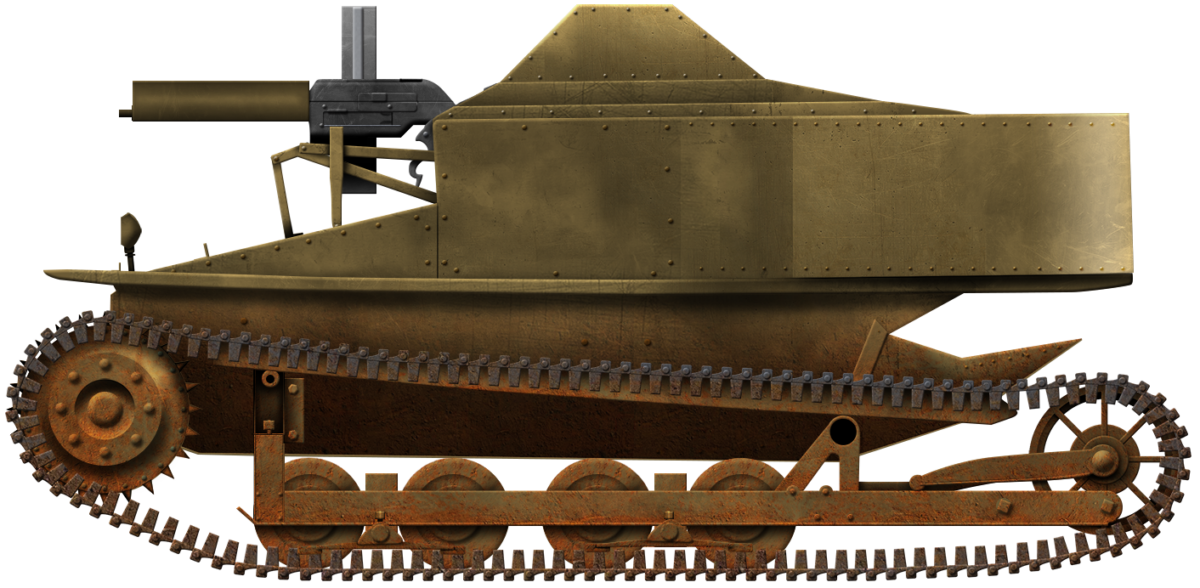

Similarly, Czechoslovakia also had good cooperation with the Yugoslav Royal Army. Both countries were members of the so-called ‘Little Entente’, the alliance formed in 1920-21 between Yugoslavia, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia possessed two well known military weapon manufacturers, Škoda (Pilsen) and Českomoravská Kolben-Daněk, ČKD (Prague). Škoda officials presented their new OA vz.27 armored car to the Yugoslav delegation during 1930. While the Yugoslav delegation was interested in this vehicle, due to its high price, nothing came from this. In 1933, both companies presented their new tankette designs to Royal Yugoslav Army officials. Škoda was the first to deliver its vehicle, which arrived in Yugoslavia in July 1933. A month later, the ČKD vz.33 tankette also arrived. After a series of tests and evaluations, both tankettes performed poorly. While the MU-4 had constant engine problems, the Yugoslav Royal Army showed interest in it, and asked Škoda officials to, if possible, improve its overall performance for new testing. The ČKD vz.33 tankette, on the other hand, was immediately rejected.

The Škoda engineers implemented some improvements on the MU-4, mostly regarding its weak engine, which was replaced with a stronger one. Once this and other minor modifications were done, it was once again tested by the Royal Yugoslav Army in late October 1934. While performing much better, and despite the initial negotiation for 40 such vehicles, nothing came from this.

Much later, in May of 1940, a Yugoslav Trade Delegation negotiated with the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, for the acquisition of military equipment. A total of 300 tanks were requested. While the Soviets initially agreed to this, not a single tank was ever given to Yugoslavia. The Soviets simply did not trust the Yugoslav authorities and constantly postponed the delivery of the promised vehicles.

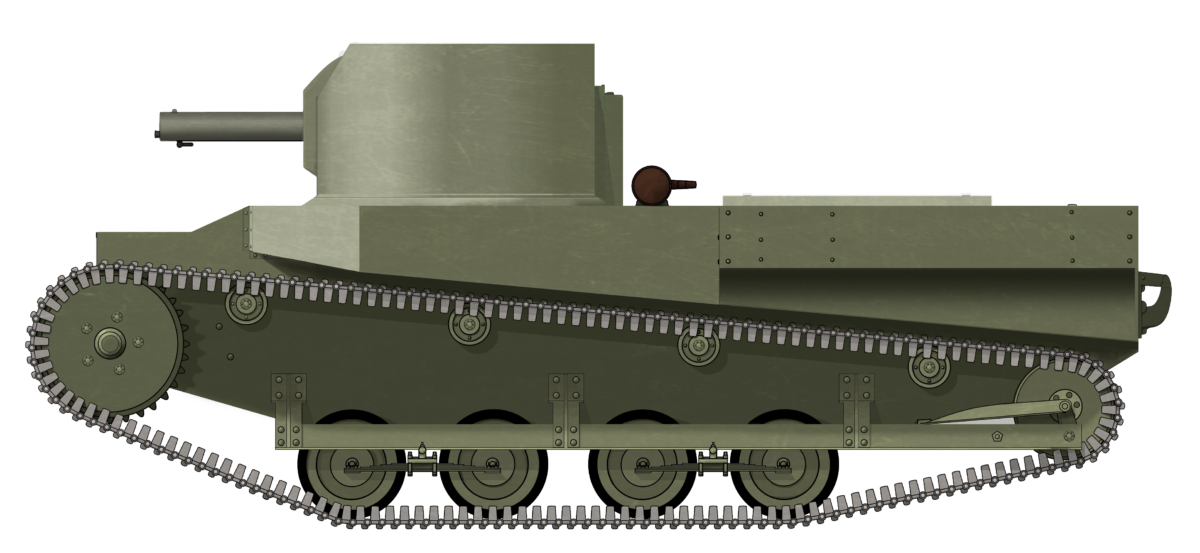

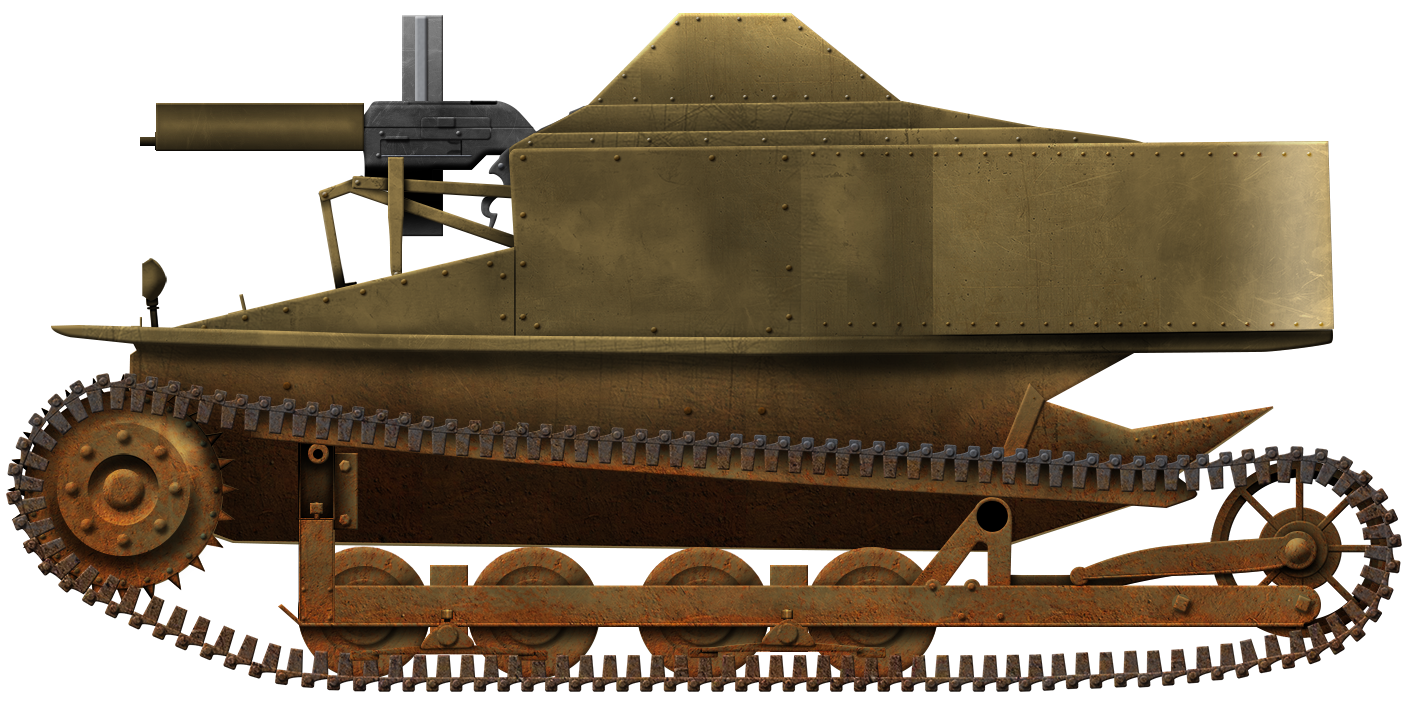

The Š-I-d Prototype

The early Škoda armored designs were mostly armed with machine guns. In 1935, its design teams began working on a new design. This time, however, the new vehicle was to be armed with one machine gun and a 37 mm gun. The prototype of this new tankette, which was designated Š-I-d, was completed by mid-1935.

The Š-I-d suspension consisted of two pairs of road wheels suspended using leaf springs. Three return rollers, a front-drive sprocket, and a rear positioned idler completed the running gear. The crews and the armament were placed in a box-shaped superstructure that had a command cupola on it. The armament consisted of a centrally mounted 37 mm A-3 gun, provided with 25 rounds of ammunition. On the front side of the front superstructure, a single 7.9 mm ZB. vz. 26 machine gun was placed with 2,600 rounds of ammunition. The frontal armored plates, which were fixed using bolts, were 20 mm thick. The sides were 10 mm, the rear 8 mm, and the bottom only 5 mm thick. This vehicle was powered by a 60 hp @ 2500 rpm Škoda engine. With this engine and a weight of 4.5 tonnes, the maximum speed was 41 km/h.

A Deal is Made

The same year as this vehicle was completed, 1935, it was presented Yugoslav Royal Army. The Š-I-d was a great improvement over the previous Škoda works, and the Yugoslav Royal Army showed great interest in it. After evaluation and testing, some changes were requested before an agreement was to be signed. These mainly included increasing the frontal armor protection from 20 to 30 mm. Strangely enough, the later delivered vehicles had a frontal armor that was slightly increased to 22 mm. Why this was not implemented or why the Yugoslav Royal Army accepted this is not clear. Regardless, the Ministry of the Army and Navy of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Škoda finally signed a contract on 30th June 1936. According to this contract, 8 such improved tankettes were bought at a total price of nearly 6 million Czechoslovak Crowns. These were to be completed and transported to Yugoslavia within the next 11 months. Due to delays in production, these were finally delivered in two batches, with the first one arriving on 14th August and the second on 25th August 1937.

While the 8 improved Š-I-d were delivered to Yugoslavia, the prototype remained at Škoda. It would remain there until April 1940, when a German SS delegation bought it. It was delivered to Germany in July 1940, and from that point on, its ultimate fate is unknown, but it was likely scrapped.

Name

The Š-I-d designation is actually an abbreviation. “Š” stands for the first letter of the manufacturer, Škoda. “I”, the Roman numeral for ‘1’, represents the vehicle category, in this case, a tankette (category II was for light tanks and category III was for medium tanks). The “d” stands for “dělový”, which was a gun-armed version designation. The improved Š-I-d was accepted into service under the designation “Брза борна кола T-32” (Eng. Fast fighting vehicle). What precisely the letter ‘T’ or the number 32 meant is not mentioned in the sources. The Royal Yugoslav Army at that time did not use the term tank. Among the soldiers that were operating these vehicles, these were known as Škoda Šid, likely imitating the name of a Serbian town named Šid.

There are some disagreements between different authors about the correct designation for this vehicle. For example, D. Babac (Elitni Vidovi Jugoslovenske Vojske u Aprilskom Ratu) mentions this vehicle’s designation as S id. B. D. Dimitrijević (Borna Kola Jugoslovenske Vojske 1918-1941) describes the prototype being named as Š-1-d, while the production vehicles were named Š1D. To further complicate the matter, H. L. Doyle and C. K. Kliment (Czechoslovak armored fighting vehicles 1918-1945) mention this vehicle as T-3D. To avoid any further confusion, this article from this point on will refer to the vehicle as the T-32.

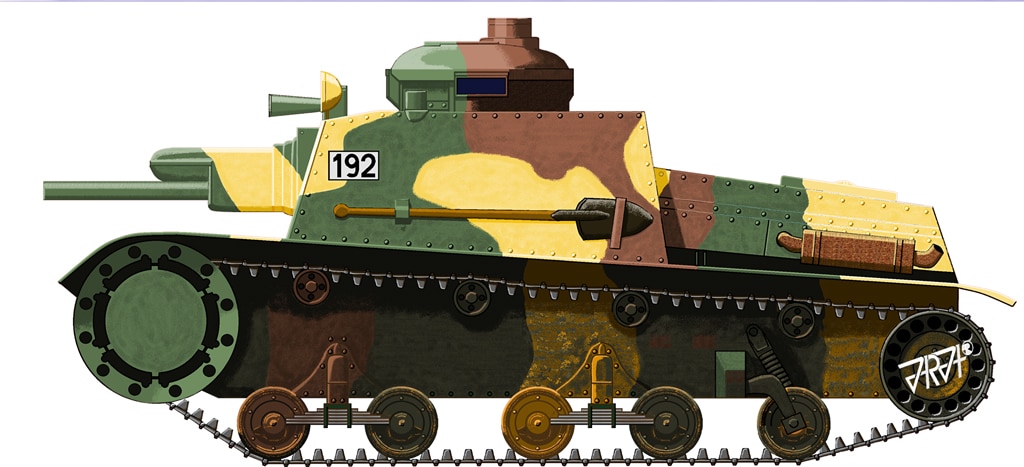

Design

Hull

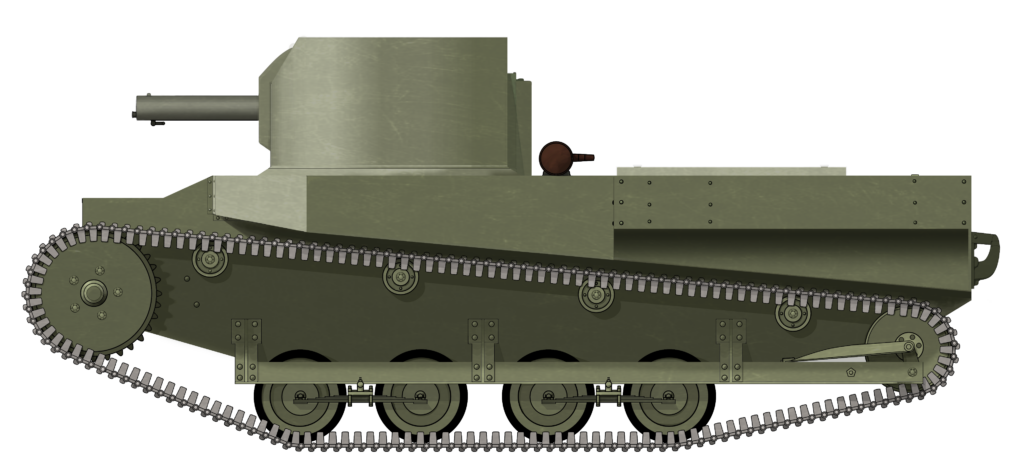

The hull of this vehicle was divided into three sections, the front part, where the transmission was positioned, the center crew compartment, and the rear positioned engine compartment. The hull was slightly shorter in contrast to the prototype, having a length of 3.58 m compared to 3.7 m. The width was almost the same, being 1.95 m, while the prototype was 2 m wide.

Suspension

In comparison to the prototype, the T-32 had a slightly modified suspension. It consisted, per side, of two pairs of road wheels, suspended by leaf-spring units, and one additional road wheel suspended on a vertical spring. There was one large front drive sprocket, rear positioned idler, and four small return rollers.

Engine

The T-32 was powered by a (sources do not give us a precise type or name) Škoda 60 hp (44.2 kW) @2,500 rpm petrol engine. With a weight of 4.8 tonnes, or 5.8 tonnes, depending on the source, the maximum speed was 41 km/h. The T-32 had a fuel load of 115 liters, which provided it with an operational range of 260 km.

The engine compartment was completely covered and protected with armored plates. On the sides of the engine compartment were two exhaust pipes. On top of the engine compartment, a large box with an unknown purpose was positioned.

Superstructure

The superstructure consisted of a simple rectangular armored shape. It was not completely flat, as its sides were slightly angled, though the precise angle is not mentioned in the sources. The front plate had an opening in the center, where the main gun was placed. Left of it was a small observation port. To the right was the much larger driver visor port. If these were additionally protected with armored glass is not mentioned in the sources. There was an additional visor port placed to the right of the driver. The rear plate was used to store two spare road wheels. Additional working tools could be attached to the superstructure sides.

The superstructure top plate was mostly flat, with a small portion of it being slightly curved toward the front of the vehicle. On the left, a large round-shaped command cupola was positioned, with a much simpler hatch for the driver next to it. The commander’s cupola was provided with four large observation ports, each placed to cover one side of the vehicle. On top of the cupola, a cylinder-shaped object probably served as a flag port that was used by the commander to communicate with other vehicles.

Armor

The T-32’s armor consisted of armored plates that were held in place using bolts. The front armor was 22 mm thick. The side armor was 12 mm and the rear was 8 mm thick. The vehicle’s bottom was only 5 mm thick. This vehicle was very lightly protected. Its best protection was its small overall size. These armor values are taken from N. Đokić and B. Nadoveza (Nabavka Naoružanja Iz Inostranstva Za Potrebe Vojske I Mornarice Kraljevine SHS-Jugoslavije). On the other hand, D. Denda mentions that the maximum armor thickness was 30 mm.

Armament

For its small size, the T-32 was remarkably well-armed. Its main armament consists of a Škoda 37 mm ÚVJ gun (sometimes called Škoda 37 mm A3). Part of the gun and its upper recoil cylinder were protected with a steel jacket. The elevation of this gun was -10° to +25°, while the traverse was 15° in both directions. It was a modern gun at that time and could penetrate some 30 mm of armor at 500 meters. The composition of the ammunition load varies between the sources, with authors disagreeing between 25 to 42 rounds.

Secondary armament included a ZB vz.30 J machine gun. It was positioned in a small ball mount on the right side of the vehicle’s superstructure. The elevation for the ZB vz.30 J machine gun was -10° to +20°, while the traverse was 15° in both directions. The ammunition load consisted of 1,000 rounds.

Crew

The T-32 had a crew of two, including the commander and the driver. The commander was positioned on the left side of the vehicle. Besides commanding, the commander was also responsible for operating the main gun, including finding targets, loading the gun, and firing it. The driver, who was positioned on the right side, operated the machine gun. Due to the small size of the vehicle, no more crew members could be placed inside it. This arrangement greatly diminished the effectiveness of the crew, as they were simply overburdened with the different tasks that they had to perform.

Service Before the War

Once in Yugoslavia, these 8 vehicles were used to form the Eskadron brzih bornih kola (Eng. fast combat vehicle squadron). This was divided into two platoons, each with four vehicles, supplemented by two armored cars, and two improvised armored trucks. The squadron was stationed at the Cavalry School in Zemun, near Belgrade.

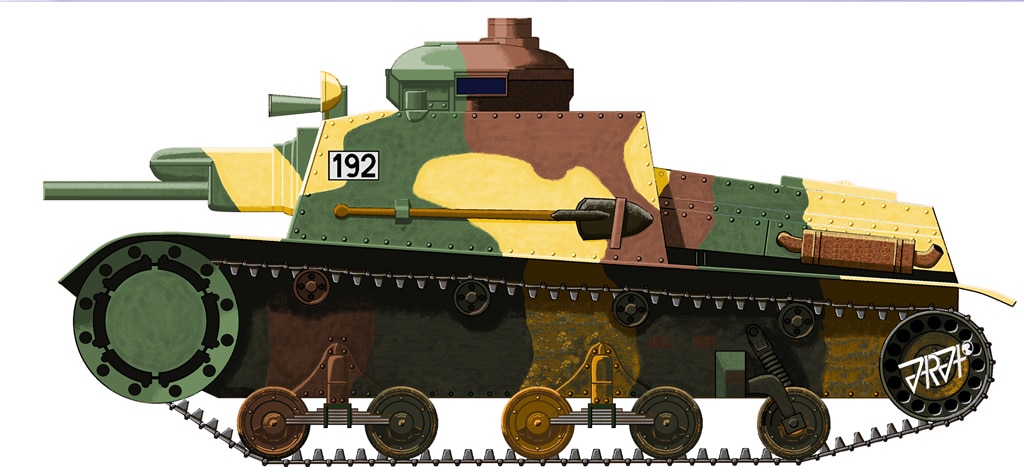

While more modern than other armored vehicles that were in Yugoslav Royal Army service, the T-32’s performance was somewhat disappointing. While it possessed good firepower, its weakest part was the poor suspension design, which made it prone to frequent breakdowns. This, in turn, meant that only a few vehicles were operational at any given time, while the remaining ones had to be sent to an army workshop for repair. In the Yugoslav Royal service, the T-32s were painted in a three-tone camouflage of brown, green, and ochre.

In the lead-up to the war with the Axis powers that began in April 1941, the T-32s were extensively used in various military exercises and occasionally on parades. The T-32s were involved in military exercises at Ada Ciganlija, near Belgrade, in 1940. These exercises were actually the first-ever recorded color documentary videos made in Yugoslavia.

In March 1941, the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was negotiating with the Germans to join the Axis powers. A group of pro-Western Yugoslav Air Force officers, under the leadership of General Dušan Simović, staged a coup on 27th March 1941 in order to prevent this from happening. They were supported by the R35 tanks, which were deployed at key locations in the capital Belgrade. The T-32s were not initially involved but would participate in the parade in honor of the success of the coup later that day.

Tactics of Employment

Despite the appearance of an anti-tank or an assault vehicle, like, for example, the German StuG III series, according to the Royal Yugoslav Army, the T-32 was meant to fulfill the role of a support weapon. It was intended to perform a few different tasks. Reconnaissance of enemy flank positions and attacks on enemy flanks and vital points, but only in cooperation with other units. Frontal direct attacks were to be avoided as much as possible. These were only permitted when the enemy was caught off guard and if sufficient artillery support was available.

The T-32 could act as a vanguard, when a platoon would be divided into two groups of two vehicles. The first group would advance, while the second would remain in reserve. In rearguard operations, the T-32 was to attack enemy flanks and thus slow down their movements.

Thus, the T-32 was not intended as a vehicle that would lead an attack, but instead as a support element for other units. To maximize its effectiveness, the crew were to use its low silhouette, good speed, and firepower, and if possible, with a factor of a surprise to their advantage.

Some sources, such as L. Ness (World War II Tanks And Fighting Vehicles) wrongly identify it as an anti-tank vehicle. Despite having a gun with good anti-tank performance against lighter armored targets, the Yugoslav Royal Army never intended it to solely fulfill this role.

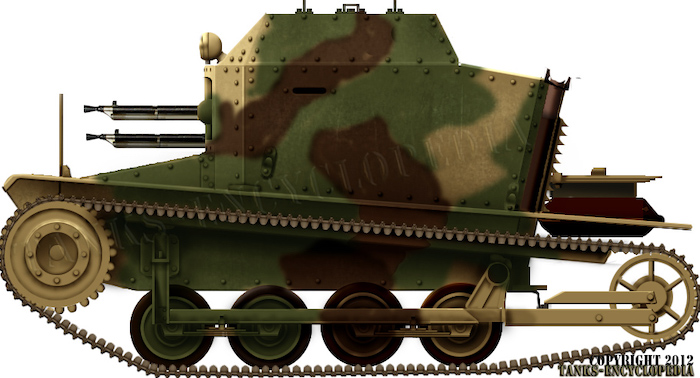

The Improved Š-I-J

After initial experiences with the T-32, the Yugoslav military leadership asked Škoda to develop better armored and armed vehicles with a more reliable suspension. In 1939, Škoda presented an improved tankette designated Š-I-J (‘J’ for Jugoslavsky/Yugoslavia) to the Royal Yugoslav Army. While visually quite similar to the T-32, it incorporated a number of improvements, mainly regarding armament and suspension. The Yugoslav Royal Army was pleased with this new model and was interested in purchasing 108 such vehicles, however, nothing came of this in the end.

In Combat

Just prior to the Axis attack on Yugoslavia on 6th April 1941, the squadron of fast combat vehicles, with all 8 T-32s, was based in Zemun. This unit was also supplemented with an old First World War-era armored car and two indigenously armored trucks. The primary mission of this unit was to protect the capital Belgrade from any possible enemy attack from the north or an airborne assault. The commander of the unit at that time was Cavalry Major Dušan G. Radović.

While the Axis attack was anticipated, the Yugoslav military planners failed to estimate its sheer size and speed of advance. Almost from the start, the Yugoslav Royal Army was in complete disarray and chaos, with the majority of units failing to fully mobilize their manpower. The squadron of fast combat vehicles did not participate in the war up to 10th April. Given the Axis attack from Bulgaria in the east, this unit received an order to move and protect the Belgrade-Niš area. As it moved toward the city of Niš, it was meant to establish a new base of operations there and go under the control of the command of that area. Due to the general chaos, as the unit was leaving Belgrade, it was ordered by the Commander of the Srem Division to proceed toward the Mladenovac-Aranđelovac area and finally to the city of Topola. At least one T-32 had to be abandoned in Belgrade due to a mechanical breakdown. This particular vehicle was captured by the advancing Germans. Interestingly enough, the T-32s were, due to an unknown reason, not supplied with anti-tank rounds at this point, only with high-explosive rounds.

The unit arrived at Topola during the night of 10th April. There, it was placed under the command of the VI Army. On the following day, the unit set up defensive positions around the road that led from Mladenovac to Topola. The same day, at around 10 PM, two T-32s were ordered to carry out a reconnaissance mission toward the city of Kragujevac. The communication lines with this city were lost and the current position of the enemy advance was not clear. Unfortunately for them, the Germans were already in Kragujevac and dispatched a small group of several tanks toward Topola. While on the way to their objective, one T-32 had a mechanical breakdown and had to be abandoned. The second vehicle, commanded by Lieutenant Ljubomir Mihajlović, continued on its own. It unexpectedly got in the path of the advancing German tanks. Both sides were probably surprised for a few minutes before the German tanks opened fire. Lacking anti-tank rounds, Lieut. Ljubomir Mihajlović could do little to oppose the enemy tanks and ordered the driver to pull back to safety. On the way back, this vehicle too had to be abandoned to a mechanical breakdown.

At 1 PM, the Germans attacked the Yugoslav Topola defense positions. By this point, at least 5 T-32s were still operational. In a counter-attack attempt, the T-32s managed to temporarily stop the German advance. The unit commander’s vehicle alone managed to destroy three German tanks, including a command vehicle. Unfortunately, he was killed while trying to escape his burning vehicle, which was hit by return enemy fire. After three and a half hours of fighting, the Yugoslav positions were finally overrun. The fate of the defending T-32s is not clear. Some may have escaped the destruction of the Yugoslav forces in Topola and moved to Mladenovac, where they were finally lost.

In German Hands

The Germans managed to capture at least some of these vehicles in various conditions. In their service, the T-32 was renamed to Pz. Kpfw. 732 (j). The precise fate of these after this point is not known. What is sure is that not all available vehicles were used by the Germans during the occupation of Yugoslavia. It is very likely that all the captured tankettes were eventually sent for scrap metal at some point during the Second World War. None of the T-32s survived the war and their final fate remains unknown to this day.

Conclusion

Compared with the tankettes from other states, on paper, the T-32 was a major step forward. This tankette had a low silhouette, was fast, well-armed, and armored. However, the T-32 suffered from problems with its suspension, which was structurally very weak and prone to failures. As a result, most of the T-32 vehicles spent months in the Army’s repair workshops. The two-man crew was simply overburdened with the tasks that they had to perform. Lastly, and probably their most major issue, was their small production run of only 8 vehicles. This greatly diminished their combat use and made the acquisition of spare parts difficult given the fact that by 1938, Škoda was in German hands. Nevertheless, the T-32 provided the Yugoslav Royal Army with a more modern vehicle than its armored pool of existing vehicles, albeit in limited numbers only.

Škoda Š-I-D (T-32) specifications |

|

| Dimensions (L-W-H) | 3.58 x 1.95 x 1.76 m (11.7 x 6.3 x 5.7 ft) |

| Total weight, battle ready | 4.8 or 5.8 tonnes |

| Crew | 2 (commander, driver) |

| Propulsion | Škoda 60hp (44,2 kW) @2,500 rpm petrol engine. |

| Speed | 41 km/h (25.4 mph) |

| Range | 260 km (161 miles) |

| Primary Armament | Škoda 37 mm ÚVJ |

| Secondary Armament | 7.9 mm ZB vz.30 J |

| Armor | 5 – 22 mm (0.1 – 0.8 in) |

Sources

- B. D. Dimitrijević (2011) Borna Kola Jugoslovenske Vojske 1918-1941, Institut za savremenu istoriju

- B. D. Dimitrijević and D. Savić (2011) Oklopne Jedinice Na Jugoslovenskom Ratistu 1941-1945, Institut za savremenu istoriju

- Istorijski Arhiv Kruševac Rasinski Anali 5 (2007)

- N. Đokić and B. Nadoveza (2018) Nabavka Naoružanja Iz Inostranstva Za Potrebe Vojske I Mornarice Kraljevine SHS-Jugoslavije, Metafizika

- D. Denda (2008), Modernizacije Konjice u Krajevini Jugoslavije, Vojno Istorijski Glasnik

- D. Babac, Elitni Vidovi Jugoslovenske Vojske u Aprilskom Ratu, Evoluta

- D. Predoević (2008) Oklopna vozila i oklopne postrojbe u drugom svjetskom ratu u Hrvatskoj, Digital Point Tiskara

- H. L. Doyle and C. K. Kliment ( ), Czechoslovak armored fighting vehicles 1918-1945

- L. Ness (2002) World War II Thanks And Fighting Vehicles, HarperCollins Publication

- D. Denda (2020) Tenkisti Kraljenive Jugoslavije, Medijski Cetar Odbrana

- http://srpskioklop.paluba.info/skodat32/opis.htm

- http://beutepanzer.ru/Beutepanzer/yougoslavie/t-32.html