Something New on the Western Front

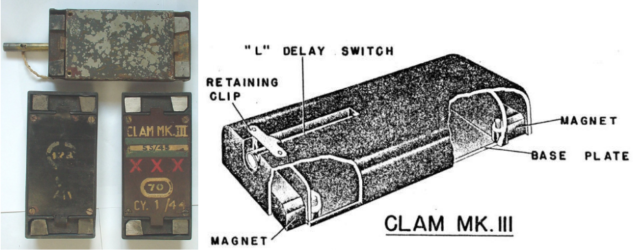

Zimmerit had been deployed ostensibly by the Germans as a counter to magnetic mines. Whether Zimmerit actually worked or not is hard to tell, as neither the US, Soviets or British made any notable use of magnetic charges. The British did have the ‘Clam’ magnetic charge from 1939 and by 1946 had supplied some 159,000 examples to the USSR, but there is no information available as to how much use these may have been put to. This rather small device contained just 8 ounces of TNT (227 grams).

The ‘Clam’ Magnetic charge. Mk.I had a metal body and the Mk.II was Bakelite but a smaller charge than this Mk.III version

The British, first encountered Zimmerit in 1944 and like the Soviets before them were intrigued by this textured coating on German tanks and in particular considered it some kind of clever camouflage. Such textured coatings had been previously encountered on items like helmets at least as far back as WW1, so the theory of camouflage by textured coatings was perfectly sound.

The British way

The British however did not have any Zimmerit material for testing at the time but even so conducted their own experiments into textured camouflage. One of these experiments in August 1944 involved the fitting of ribbed rubber material to the outside of the turrets of Cromwell tanks belonging to C Squadron, 2nd Northants. Yeomanry, 11th Armoured Division.

Cromwell tanks of C Squadron, 2nd Northants, Yeomanry, 11th Armoured Division with rubber material glued to turret

As a camouflage, Zimmerit was drawing attention from Field Marshal Montgomery who expressed the need for improved camouflage. On the 21st February 1945 he remarked that “a satisfactory camouflage is required which will eliminate all shine and reflection from the armour plate. Some form of plaster like the German ‘ZIMMERIT’ should be produced and incorporated in the manufacture of all future tanks”. Stocks of captured German Zimmerit were not available until August 1945 though, and in the meantime further experiments included test applications were carried out. These experiments used a Ram Sexton Self Propelled Gun, a Churchill tank, a Cromwell tank, and the gun shield of a 25 pdr field gun.

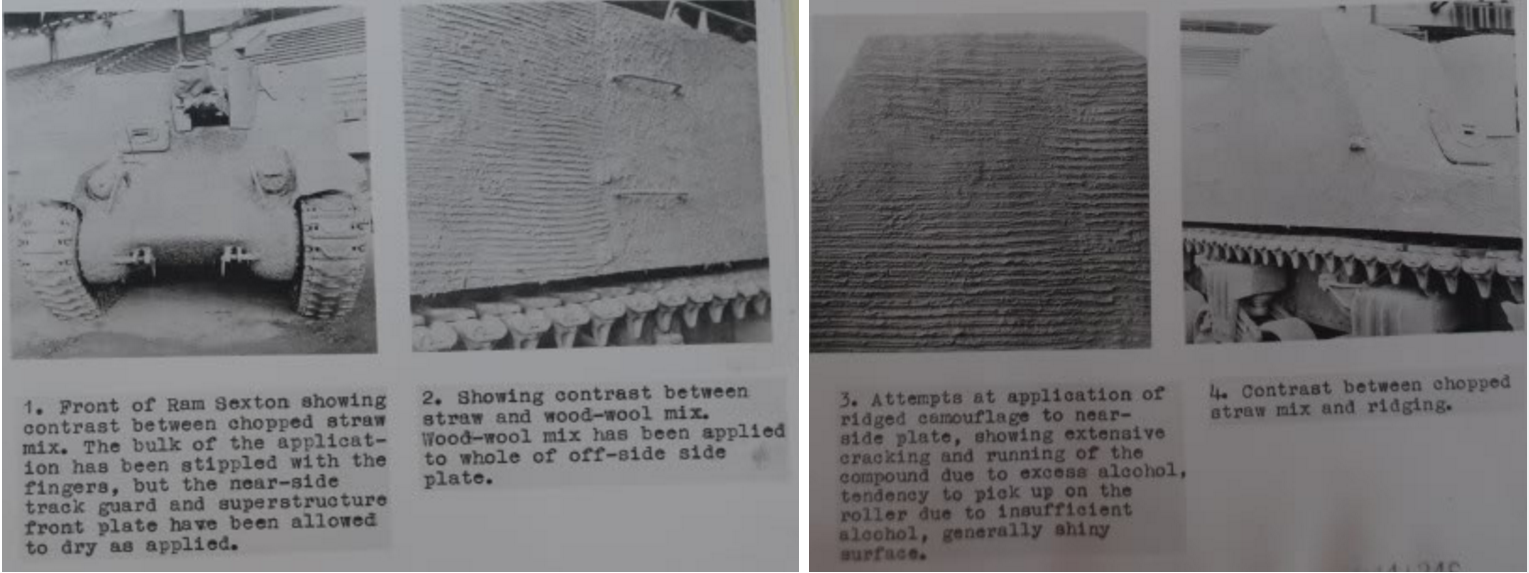

Test results for the Ram Sexton

The Ram Sexton had a coating applied to it made from a chopped straw mix and also from a wood-wool mix to show texture differences, the exact consistency of this material is unclear but it was alcohol based, probably because it would dry and harden more rapidly as the alcohol evaporated. It was applied by means of a roller with the intent to then add ridging from either fingers drawn across the surface or with a special texturing wooden roller. If the mix was off and contained too much alcohol the surface could become shiny or simply crack and flake.

The tests of this paste were carried out in the ETO (European Theatre of Operations) in April 1945 on vehicles of the 256th Armoured Delivery Squadron. This ‘plastic’ type substance was initially applied by means of spraying (application by spraying was found to not suit the later texturing) but also by trowel and took no less than 80 man hours to apply to the Cromwell. Despite the use of alcohol, it took 2 days to dry although it is possible that the mixture was too thick or the application untried, as application on other vehicle was quicker. The most successful mixture tried involved the chopped straw and the images show an extremely well textured surface.

Close-ups of different textures obtained

The Cromwell required some 5.5cwts (279kg) of this material in order to be fully coated, with care taken not to obstruct the air intakes or exhausts. The Churchill tank required some 6cwts (305kg) of material, took 2.5 days to dry and 95 man hours to apply, whereas the Ram Sexton only required 4cwts (203kg), 51.5 man hours to apply and a day and a half to dry. The 25pdr gun shield needed just 1.5 man hours to apply the 0.5cwts (25kg) required and the overall results were judged to be ‘extremely effective’.

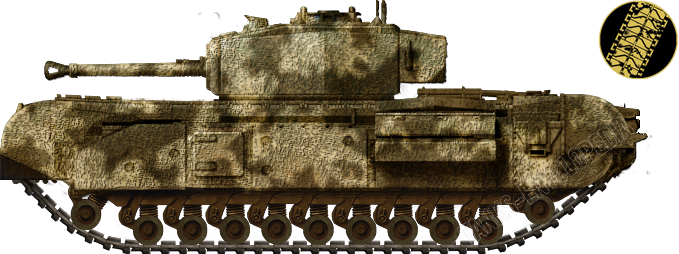

Color photo of the Cromwell with rubber stripes on its turret.

Cromwell Mk.IV “Agamemnon” with rubber stripes, 3nd Northamptonshire Yeomanry, 11th Armoured Division, Normandy, 1944.

Patterned camouflaged coating on a Churchill tank

Side-note: Paint and magnetic mines

Churchill tank demonstrating the effectiveness of a textured and painted coating as camouflage.

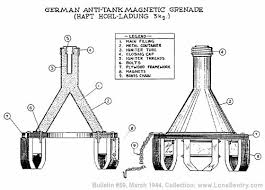

An additional curious side note is that, over the top of this coating, the vehicles were painted in a two-tone matt black and German yellow-green paint scheme. The Cromwell in particular was impressive, as it could “completely disappear into the background”, especially when fitted with a camouflage hessian net over the suspension units. There is no record made as to British testing this scheme against the standard German magnetic mine; the 3kg Hafthohlladung, although the British were aware of the ‘anti-magnetic charge’ purpose of the material.

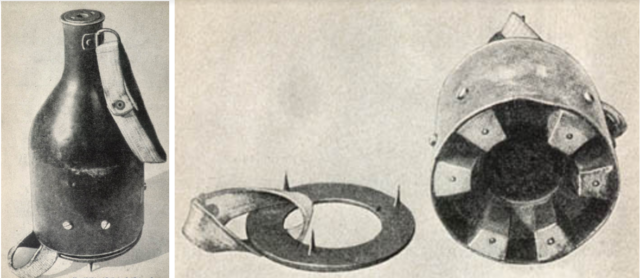

The Hafthohlladung mine used three large magnetic feet to adhere to the armor of a vehicle and the shaped charge could pierce 5” inches of armor plate at a 90 degree angle. There was a smaller German magnetic version from the Luftwaffe, known as the Panzerhandmine 3 (P.H.M.3), which had the appearance of a small wine bottle with the base cut off to make room for 6 magnets.

Hafthohlladung mine showing method of use

German Panzerhandmine (P.H.M.) 3

The end of the war, the start of the tests

The British study mission into Zimmerit did not manage to confirm that the firm of C.W. Zimmer originated the Zimmerit paste, although it seems highly probable they were. Having liberated 100 tons of the stuff the British had plenty of Zimmerit to finally test out though but it had come too late.

The War in Europe was over before any British trials involving this paste or imitation substance had any effect on the outcome, so the liberated stocks were shipped to Australia, presumably for trials against the Japanese magnetic mines. The War in the Pacific was also finishing so the Australians do not seem to have had any use for this weird substance either and there are no records of what, if anything, was done with their shipment so it seems that all of the effort that went into tracking down the source of the substance and getting hold of some was wasted.

Sherman tank painted half and half with Zimmerit paste

Overall, the British opinion was that a textured coating provided excellent camouflage and that texturing made no difference at all to the anti-magnetic mine benefit. One further thing worth noting though was that when the British tested the substance on a tank by means of a flamethrower than the uncoated vehicle got so hot inside that the ammunition could ignite however the coated vehicle remained at bearable temperatures. This lends more credibility to the Soviet report suggesting some fire or heat protection from the material although the mode of protection is more likely simply by means of insulation than anything else.

The war in Europe and in the Pacific was over before the British or allies could deploy anti-magnetic coatings for either protection from mines or for camouflage. The US were to conduct their own experiments but the only other experimental work which appears to have been done on Zimmerit is by the French who tested a very well patterned application on the hull of a M4A2.

Other articles in this series

Part I: Zimmerit in German Use

Part II: Zimmerit in Soviet and German tests

Part IV: US work on anti-magnetic coatings

Links & Sources

The links and sources can be found in part I of the Zimmerit series