United Kingdom (1907)

United Kingdom (1907)

Trench-cutting Machine – Fictional

Introduction

There are numerous characters who are notable in the history of the development of tanks. Some of the names involved which stand out are well known even if their role was a secondary or tertiary one, but such people include Sir Winston Churchill, H. G. Wells, Sir Ernest Swinton, Sir William Tritton, Colonel Rookes Crompton, Walter Wilson, etcetera. One person who has been virtually erased from the origin story of the tank in WW1 is Captain Charles Vickers. Vickers had a successful military career and was on the cusp of a successful writing career when he was tragically struck down with illness and died in early 1908. The result was that his writings and ideas have become lost or distorted by the chaos of WW1 and the myriad of claimants who wanted their share of fame and fortune for the invention of the tank. Captain Vickers, however, has a valid claim, certainly more so than many to his share of credit and his work can be seen as an inspirational factor for Swinton as well. Vickers’ ‘Snail’ might not have the fame of Wells’ Ironclad, but it is more valid as an idea of future armored warfare coming from a professional soldier rather than ‘just’ a writer of popular fiction.

The Man behind the Snail

Charles Ernest* Vickers was born on 23rd February 1873 in Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland, the youngest son of a notable local barrister Henry Thomas Vickers. He also had military heritage in his blood as his uncle was Major General John William Playfair R.E. (Royal Engineers). Educated in Dublin from 1885 to 1887, Vickers then went to Clifton College, in Bristol that September and then switched his interests from classics to military and engineering aspects.

(* His middle initial is mistakenly given as ‘C’ in the Irish Times of 12th February 1908)

Gifted as a mathematician and artist, he left Clifton College in 1890 to attend the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Vickers excelled at the academy finishing top of his class and winning the Pollock Medal (July 1892) as well as numerous prizes for his work on fortifications and artillery amongst others.

He was commissioned from the cadet company as a 19 year old 2nd Lieutenant on 22nd July 1892, to the School of Mechanical Engineering at Chatham finishing there in September 1894. He then went to the Midland Railway for Instruction in rail traffic management in October 1894. He would finish there in November 1895 during which time, in July 1895 he was promoted to lieutenant.

He then spent nearly two and a half years working on the railways at Woolwich with 10th Company Royal Engineers before a posting to Malta in April 1898 and then South Africa in October 1899. He was in South Africa for just 75 days working with 42nd Fortress Company before moving on 1st January 1900 to South Africa taking a position as a railway’s staff captain with responsibility as a Traffic Officer.

He remained in South Africa in this role and according to his service record took part in operations in the Orange Free State between March and May 1900, followed by operations in the Transvaal, east of Pretoria from July to November that year. During this service in the Transvaal, Vickers saw combat in Belfast in August. Between May and July 1901, he took part in operations in Orange River Colony followed by operations in Cape Colony, south of Orange River. He saw combat once more at Colesberg, and for his service was awarded the Queen’s Medal with 3 clasps and then the King’s medal with 3 clasps.

With the end of the Second Boer War in July 1902, Vickers was still in railway work having become the Deputy-Assistant Director of Railways (in October 1901). During his time in South Africa, he would have been familiar with mobile armored warfare in terms of armored trains. These were used extensively during the war and he would know at least the rudimentary elements of what to protect and how on a machine. Given he remained in South Africa through to the end of the war, he may also have seen Fowlers Armoured Road Train and gain some additional insight into armored warfare – this time on land.

Source: The Engineer

He returned to the UK in November 1902. After a period of leave, he was posted to Salisbury Plain in March 1903 and then promoted to the rank of captain on 20th April. His posting at Salisbury Plain ended in May 1903 with a move to the Inspector General of Fortifications’ office. He stayed there until March 1905, and on 1st April 1905, Vickers was appointed to Headquarters as a staff captain. His next deployment was to be Gibraltar, but the recently engaged Captain and distinguished veteran of the South African wars fell ill. He passed away on 6th February 1908 aged 34 in London having served for nearly 16 years including nearly 5 years of overseas service. His cause of death listed on his death certificate was “Pleuro Pneumonia Meningitis” (Pneumococcal Meningitis), having passed away during surgery to treat it. He was buried with full military honors in Dublin on 11th February 1908.

His obituary, published in the Journal Of the Royal Engineers in June 1908, and penned by Ernest Swinton himself was a touching and friendly list of Vickers’ life and accomplishments including:

“…many articles from his pen appeared in different periodicals. His last finished effort in this direction – a story of war – appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine only a month before his death under the pseudonym of ‘105’.”

The story to which Ernest Swinton was referring in this part of Vickers’ obituary was a short story titled ‘The Trenches’, and it is in ‘The Trenches’ that Vickers describes ‘The Snail’.

Stories

Shortly after coming to Staff Headquarters in 1905, Vickers began writing more stories and articles just as he had done during his service in Malta. His writing and illustration skills were notable and he would start working collaboratively with Swinton on several occasions with the results published in Blackwood’s Magazine (known by its readership as ‘Maga’).

‘The Trenches’ story is set in a fictional War Office department with a pair of officers, Major Swann and Captain Marshall, looking over designs.

In the tale, a “keen-faced restless-looking citizen of the United States” called Mr. Sandpaper, interrupts these two officers and while approaching Major Swann says “You will be interested in this here machine, Major. It’s just about the latest and cutest idea in trenching machines – trench along through any darned thing: just set the depth, and it’ll go along any distance you please, and you can follow up with the pipes as fast as your men can lay them”.

“For the moment things seem to be at a deadlock; the armies have been at grips; but have had to draw off without any advantage gained on either side. It almost seems as if the conflict were like to resolve itself into pseudo-siege operations. And yet how suddenly may the kaleidoscope of war be shaken and the picture by changed”

In the next scene, at the General’s office, staff officers are reviewing a map of the war showing a static set of lines. There is the sound of gunfire in the distance but the enemy lines remain unbroken. In order to get to the enemy lines, assault trenches have to be dug as without them, they are suffering heavy casualties. At this time, Chief Engineer Colonel Spofforth came in and was briefed on the situation. Here, Col. Spofforth proposed a new solution, the use of the freshly prepared “trenching machines” to lead the assault. This is agreed to, leading to the third and final scene, the attack of the ‘Snails’.

In this scene the reader is provided with a description of the night before the battle as these machines are brought up to the front and get to work and the soldiers who are resting are disturbed by a strange sound “…Resting! No; there is a new sound. Somewhere down below something has begun to be busy. Something is at work amid the mists of the plan. It is as if a little reaping-machine had set to cut some ghostly corn. No, not quite a reaping-machine – more like a mammoth deathwatch. It must be some strange animal: something endowed with life, for is not that another calling to its mate?”

Here, Vickers provided some critical information for his idea. A mechanically propelled machine making strange mechanical noises and seemingly alive as it goes about its business cutting an attack trench for the soldiers to use the next day. Further, the shape of the vehicle clearly delineated it as no agricultural device but more like a ‘deathwatch’.

This reference can be two fold, firstly in terms of shape with a dark-coloured rounded body and secondly as an omen. In 1907, there was effectively no stopping the Deathwatch (Xestobium refovillosum) beetle’s progress if it happened to infest your home as it devoured the timbers (mainly oak), but more importantly that it was seen as an omen of foreboding. In folklore, the clicking noises it makes was associated with death (hence the name). The Deathwatch beetle has been the subject of stories by such notable authors as Edgar Allen Poe in 1843 and Beatrix Potter (1903). In a modern understanding of the beetle, the tapping noise it makes is not only audible but may also be being used as an allegory in the story for bursts of machine gun fire.

Source: Wiki via Gilles San Martin

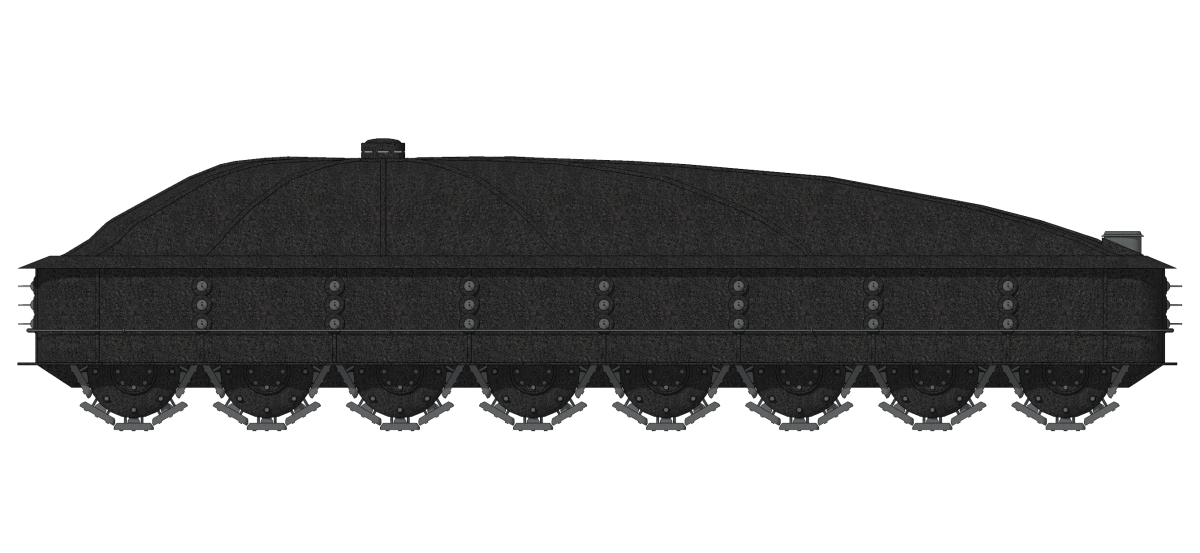

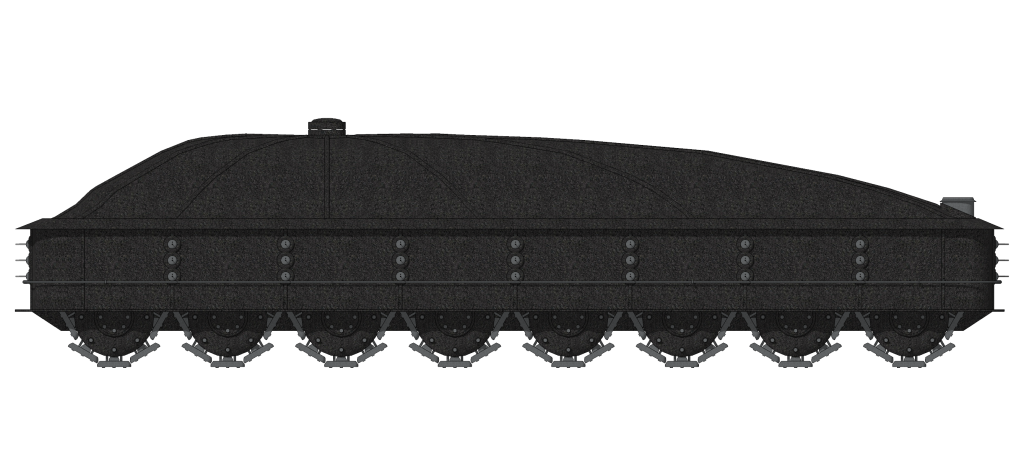

As the attack goes in, the narrative shifts to one presented almost in a Wellsian fashion from the point of view of a reporter. Here, the reporter struggles to describe what he is seeing saying: “The machine!… But it seems such a simple, almost obvious notion to evolve a machine that shall dig trenches, that shall be able to move unconcernedly across open ground where no man can show himself scatheless, secure under its turtleback of steel, inconspicuous, minding all the hail of lead as little as rain … They have nicknamed it The Snail but it can burrow forward like a mole!”.

Adding the smooth rounded type of carapace as found on the insect shaped description before the journalist, via Vickers writing, is clarifying that it is indeed a large rounded outer shell and that it was to be made of steel. Given that in the account, the machine can travel “unconcernedly across open ground” it indicates sufficient armor to be proof against fire as well

“fighting in the trenches is veritably a bloody affair”

With the Snails moving forwards purposefully and carving out avenues for the soldiers to follow behind it, the attack then goes in. With these ‘Snails’ on hand, the soldiers did not have to dig attack trenches and instead could follow the trail of the machine, covered from enemy fire right up to the point of attack. At one point, the correspondent reporting on the scene describes seeing one of the ‘Snails’ come out of a trench “half concealed in a cloud of dust” and having cut far enough forwards it halts. The men bring up a mortar to bombard enemy positions from the shelter of the trench dug behind the machine and thereafter assault the enemy lines on the hill. The final outcome is a positive one to validate the utility of the machines, the enemy forces are driven from their defensive positions despite the loss of a few Snails to enemy artillery fire.

Method of Attack

In considering The Snail in Vickers’ story, the first obvious comparison is to what is considered as a tank. A more apt comparison however, might be to a more unusual machine known commonly as ‘Nellie’. In 1940, ‘Nellie’ (Cultivator No. 6) was a project by the Naval Land Equipment (N.L.E.) to create a tracked assault machine.

Source: Wiki.

‘Nellie’, like Vickers’ Snail, was to advance forwards creating a trench and discarding spoil to the sides as it went. Whereas Nellie simply used a giant plough and the power from its engines to drive that forwards, the Snail was described as using actual cutting equipment instead. Indeed, the closest machine to the Snail in both operation and date might be that of William Norfolk in 1916. That vehicle operated on wheels and used a large cutting face along with a means to discharge spoil to the sides. It too would cut a trench as it went, albeit for slightly different purposes.

Design

Armor

Just as H. G. Wells had described a cockroach like machine in his 1903 story, the Land Ironclads, Vickers also used an insect analogy. His choice was described as Deathwatch Beetle-like and also as a rounded steel body. Both designs, therefore, adopted a low rounded armored shell to protect their respective machines.

No specific thickness of armor is mentioned by Vickers but he does say the vehicle could cross no-mans’ land area without harm, so at least, protection from machine gun and rifle fire is implied. He also clarifies within the story that during their cutting of zig-zag-shaped assault trenches, some were wrecked by enemy artillery, so the armor was by no means impervious to all enemy fire.

Armament

No specific offensive weaponry is mentioned in Vickers’ story. Nonetheless, that is not to say that his vehicles would be unarmed. First and most obviously is the trenching, cutting, nature of the vehicle. Driving itself ahead, half submerged in the ground as it advanced, it would destroy anything in its way, whether trench, parapet, or enemy soldiers.

The next point from Vickers’ story was that tapping Deathwatch Beetle noise. It could be taken as implicitly referring to machine gun fire either incoming or outgoing, in which case the vehicles would be armed. Using men inside with rifles to fire would not really fit with the experience of a military man who would know that firing from a moving vehicle would produce very poor results. He had seen combat and understood the value of well-placed fire. Any vehicle with no guns would provide substantially less value in combat than a vehicle with even the most modest of armament and it is difficult therefore to contemplate Vickers’ machine without at least one machine gun located in the area above the digging line. Nonetheless, the omission of any direct mention and that at one point the crew is implied to consist of just one man as a ‘driver’ suggests that they may have been armed only with their cutting equipment.

As a side reference, Vickers’ comments on the use of a mortar directly behind the ‘Snail’ in the assault is almost eerily similar to an idea trialed in 1917 to bring heavy fire support along with a tank. The 1917 experiment involved a 6” (152 mm) Stokes mortar on a platform between the rear horn of a Mk.IV tank fitted with the tadpole track extensions, whereas Vickers had considered a mortar being brought up behind the machine separately. In effect, the idea of a mortar behind the tank is identical, except that by attaching it, the effort for the men was much reduced. Either way, it demonstrates once more the difference that the experience, and specifically, the combat experience of Captain Vickers made in his story. He was able to apply his experiences to consideration of a whole new type of warfare and did so rather well.

Source: wiki

Automotive Elements

The most complex part of Vickers’ tale to unravel is the means of propulsion envisaged for the device. On the face of it, the vehicle might be surmised to be a simple wheeled vehicle with this new carapace fitted. It was, afterall, described as a trench cutting machine at the start of the story and at the time of writing in 1907, there were not many tracked vehicles around. That is not to say that there were none, and Vickers’ colleague Ernest Swinton would even end up reviewing tracked vehicle trials in 1908 for the Ruston-Hornsby design.

Source: Lincolnshire Film Archives.

Ignatius Clark, in his book Voices Prophetizing War (1993), suggests that the vehicle was meant to be tracked, based, it seems, on the ‘Snail’ like description. A hard shell and a slow steady creeping form of motion like a real Snail would certainly allow for this interpretation. However, perhaps Vickers did not wish to commit himself to a specific form of traction, as afterall, such a thing was not necessary for the plot of the story. The only hint he provides in fact is the mention of the use of petrol as fuel meaning that a steam traction engine can at least be excluded.

Forgetfulness or Betrayal?

As a prelude to a conclusion about the actual machine in Vickers’ story there is an important element to consider in terms of ‘invention’. Specifically, the old question of who invented the tank. Ignoring the too-often cited wooden cart of Da Vinci, the reality was that until the advent of mechanical propulsion, a self-propelled fighting machine was effectively out of reach. Likewise, until the use of tracks became viable with the Hornsby-Ackroyd being the first notable example in 1908, the passage of those vehicles over soft ground was so problematic as to preclude the widespread use of armored vehicles.

The writings of H. G. Wells in 1903 with The Land Ironclads is also often cited as an important factor and the result of the 1919 Royal Enquiry into the invention of tanks made reference to it as well. The man most directly responsible for the invention of tanks according to that enquiry was none other than Major General Sir Ernest Dunlop Swinton. Swinton was sure to make a good account of himself in the inquiry. This was followed by numerous speeches, public engagements, and publications including his autobiography Ole Luk-Oie published in 1951. Swinton did well for himself as the recipient of a substantial financial award by the Royal Enquiry, as well as in his later ventures, yet nowhere in any print or speech did he mention Vickers. He did mention Wells, but not Vickers… but why?

When Vickers was working as a staff officer from 1906 until his death in 1908, his direct supervisor was Ernest Swinton, so he definitely knew him. Further, they worked closely together on stories, having penned An Eddy of War together which was published in April 1907. The story was a somewhat rambling tale of soldiery during an invasion of England, although it did at least put some focus on Germany as a future adversary. Nonetheless, neither this German adversary nor the invaded English of the tale use any kind of armed or armored vehicle.

Proof of their friendship comes directly from Swinton, who wrote to the editor of Blackwood’s Magazine (Mr. Blackwood also a friend) of Blackwood’s Magazine (known to its readers simply as ‘Maga’) on 29th December 1906 saying “I return proof of ‘An Eddy of War; corrected. I need hardly say that both my pal (Capt. Vickers R.E.) and I am delighted at your taking [of the story] for [publication in] Maga”. Several other times Swinton also referred to Vickers directly in his correspondence with Blackwood’s Magazine.

On 10th October 1907, Vickers wrote to Blackwood saying “It is hardly necessary to say that I feel very pleased you think ‘The Trenches’ worthy of a place in ‘Maga’. It is the first writing of my own you have accepted, though ‘An Eddy of War’ was partly mine (with Swinton)”. Swinton even remarked directly on The Trenches to Blackwood on 12th December 1907, writing “I was pleased to hear from Vickers (Capt. R.E.) that he had had a story accepted by you and I am keen to see it. It sounds like a good one”.

He then proves he has read it in a letter to Blackwood of 8th January 1908 saying “I like Vickers’s yarn… Why will our powers at home not consult the people who know, a little more?”

The Trenches was the only story of Vickers which had to that point been published (and would be the only one published in his lifetime) so the reference to “the yarn” can only be The Trenches.

Last but not least connecting these two men is a singular obituary. This was Vickers’ obituary which was published in the June 1908 edition of the Royal Engineers Journal and was written by Swinton himself. Swinton did not attend Vickers’ funeral in Dublin but he assuredly knew him and his work very well.

In his book Histories of the Future: Studies in Fact, Fantasy and Science Fiction (2000), the author, Alan Sandison contends that not only did Swinton know Vickers, was friends with Vickers and read his work, but that he was also careful not to mention his name at any point. This was, he asserts, a deliberate and intentional act to exclude Vickers’ name from the record of the inquiry into tank development or any of Swinton’s later writings. Not only this, but Sandison goes on to say that “Swinton’s exclusion of Vickers is so complete that it suggests both purposefulness and premeditation, which, if true, indicates that he feared Vickers’s vision would be seen as so informing his own that it would be taken as the true ‘source’ of the invention of the tank”. Had Swinton mentioned Vickers during the inquiry it is likely that not only would Vickers’ name be better known, but also that his family might have shared in some of the rewards, both financially and in fame. Swinton’s omission at best therefore, can be seen with a view to a motive for profit from a man he formerly regarded as a close friend and colleague.

“Had Vickers survived, it is quite possible that Swinton might not be the name associated with the invention of the tank”

Conclusion

In contrast to Wells’ rather naive descriptions of use, with the Snail, Vickers is right on the money and maybe a little too prescient in seeing a divide between trench lines as being a land “where no man can show himself scatheless” (literally a ‘no mans’ land’). This type of static war had been considered by Ian Stanislavovich Bloch which had been published in English for the first time in 1899 under the title Is War Now Impossible. In it, he theorized that the growth in range, speed, and penetration of modern ammunition meant that weapons were so deadly, armies could no longer face each other and that the next war would “be a great war of entrenchments”.

Both Bloch and Vickers predicted a static type of war, a war where opposing forces had to dig defensive works to protect from the fire of the other and through which neither side could progress very well. This too is well beyond Wells’ more limited vision of crossing enemy wire to pursue an enemy, and predicts all too well exactly the sort of warfare which would take place a few years later in WW1.

Sources:

Clark, I. (1993). Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars 1763-3749. Oxford University Press, UK.

Borthwick, F. (1912). Clifton College Annals and Register 1862-1912. Bristol, UK.

Canadian Patent CA174919 Trench Artillery, filed 21st September 1916, granted 6th February 1917

Irish Times (Newspaper). ‘Military Funeral in Dublin’, 12th February 1908.

Oakley, E. (1890). Clifton College Register 1862-1889 (Supplement). Entrances in September 1887.

Quarter 1, 1908 Death Certificates Volume 1a, No.315 Chelsea.

Sandison, A. & Dingley, R. (2000). Histories of the Future: Studies in Fact, Fantasy and Science Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan, USA.

The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. VII, No.6, June 1908.

Vickers, C. (1905). The Siberian railway in war. Royal Engineers Journal, Vol.2, August 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Transport and Railroad Gazette – Progress in yard design, The Royal Engineers Journal, 26th May 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Engineering News – Double-tracking of Railways, The Royal Engineers Journal, 14th September 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Bulletin of the International Railway Congress, The Royal Engineers Journal, September 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Electrical Review – High Speed Traction, The Royal Engineers Journal, June 10th 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Railway and Locomotive Engineering – Single Line Working, The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. 1, February 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Engineering News – Impure Sand in Concrete, The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. 1, 2nd February 1905.

Vickers, C. (1905). Railways and Locomotive Engineer. The Royal Engineers Journal, Vol. 1, 2nd February 1905.

Vickers, C. (1907). The Trenches. Published January 1908 in Blackwood’s Magazine Vol. CLXXXIII, (January-June 1908). Edition, William Blackwood and Sons, London, UK.

War Office File WO25/3917, Page 268/418, Service Record of Charles Ernest Vickers, Royal Engineers.