United States of America (1959)

United States of America (1959)

Armored Flamethrower – 351 Built

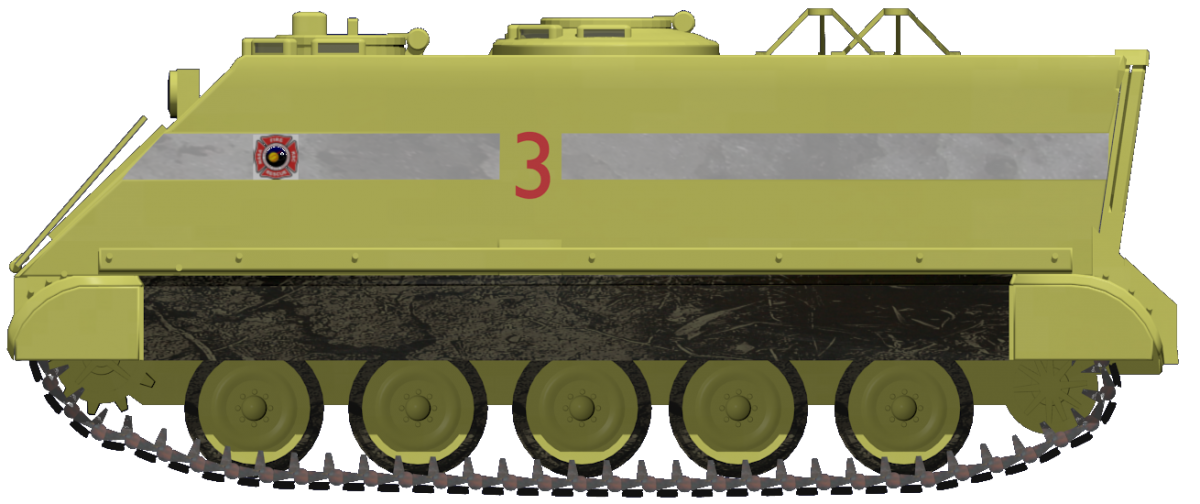

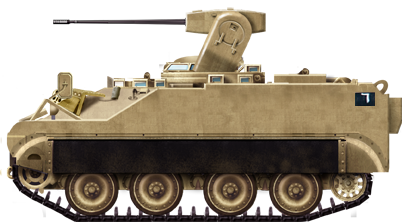

Since its appearance in the late 1950s, the Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) M113 has continued to be one of the most versatile and universal armored vehicles to have ever existed. It has spawned numerous variants in its long service life, from mobile command posts and Self-Propelled Anti-Air Guns (SPAAGs) to firefighting vehicles.

One of the less well-known variants was the Self Propelled Flame Thrower M132. Entering service in 1963, the M132 – along with the Flame Thrower Tank M67 ‘Zippo’ – would be one of the last armored or ‘mechanized’ flamethrowers to see service in the United States Military. Whereas the M67 would serve in the US Marine Corps (USMC), the M132 would serve with the US Army. The vehicle saw action during the long years of the Vietnam War (1955-75), but its time in service was, however, short-lived. This is mostly due to the fact that, after Vietnam, flame throwing vehicles began to fall out of favor.

One of the first things the article will address is its unofficial ‘Zippo’ nickname – named after the lighter brand – which it shares with the M67. Its origin is somewhat mysterious. Just like the M60A2 tank and its ‘Starship’ name, a concrete source cannot be stated as to when this name came into use. It was likely given by the crews or infantry that operated with the vehicle. There is a suggestion, however, that the name originated from this particular lighter being used to ignite the napalm fuel when the electrical igniters failed.

The M113

The M113 is one of the most famous Armored Personnel Carriers ever built and continues to serve in not only the US Military but also in the inventory of many of the world’s militaries. The vehicle has been in service for 60 years, making it one of the longest-serving armored vehicles in history.

Developed and built by the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC), the M113 is a basic vehicle, little more than an armored box on tracks. It is 15 ft 11.5 in (4.8 m) long, 8 ft 9.7 in (2.6 m) wide, and 8 ft 2 in (2.5 m) tall. The vehicle’s structure is almost completely fabricated from aluminum, including the armor which is between 0.4 and 1.4 inches (12 – 38 mm) thick. The vehicle started out with a Chrysler 75M petrol engine, although this would later be changed to a General Motors 6V53 diesel type. The power plant is located at the front of the vehicle with the transmission. The vehicle is supported by a torsion bar suspension connected to five road-wheels. The idler wheel is at the rear with the drive sprocket at the front.

The APC has a crew of two, a Driver and a Commander, who are located at the front of the vehicle, with a passenger compartment taking up the rear of the vehicle. Eleven passengers can be carried by the vehicle. The APC’s usual armament would be a single Browning M2 .50 Cal (12.7mm) heavy machine gun, located at the commander’s position.

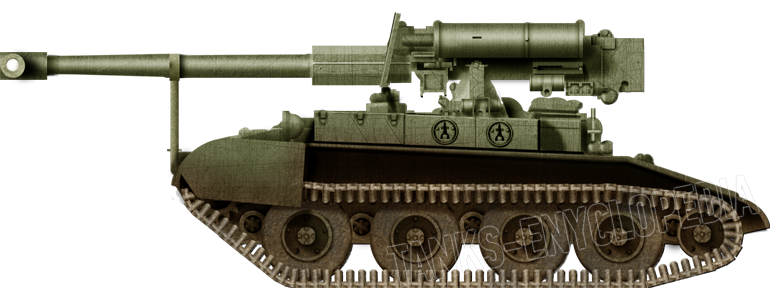

Development & Background, the CRDL

In June 1954, the Chemical Research and Development Laboratories (CRDL) began a study, conceptualized by the US Army Chemical Corps, looking into the conversion of serving tanks and armored vehicles into armored/mechanized flame throwers. As a result of this study, the E31-E36 flame thrower kit was developed. The nomenclature, which was unchanged from its debut in the Second World War, denotes that this is the combination of the E31 fuel and pressure unit and the E36 flame gun. The idea behind this kit was that it could be installed on serving vehicles with minimal effort.

Three E31-E36 kits were produced and tested on the M59 APC, the predecessor of the M113. In the M59, flame-fuel capacity was 400 gallons (1,818 liters) providing a total firing time of 70 seconds. Following the tests, improvements were made to the weapon and it received the new designation E31R1-E36R1. The modifications to this version of the weapon were intended to allow its installation not only on the M59, but also the brand new M113 APC.

Prototypes

In the summer of 1959, a contract was signed for the construction of three E31R1-E36R1 units and their installation aboard three M113s. The newer, and larger, M113 was found to be a far more suitable vehicle than the M59 and, as such, all work on an M59 based flame thrower ceased. This is despite the M59 having better flame fuel capacity, and as such, a longer firing time*. Logistically, however, it was only prudent to develop the vehicle on a new type which was then entering service. This would allow a degree of commonality, making it easier to manufacture and allowing spare parts to be shared between vehicles.

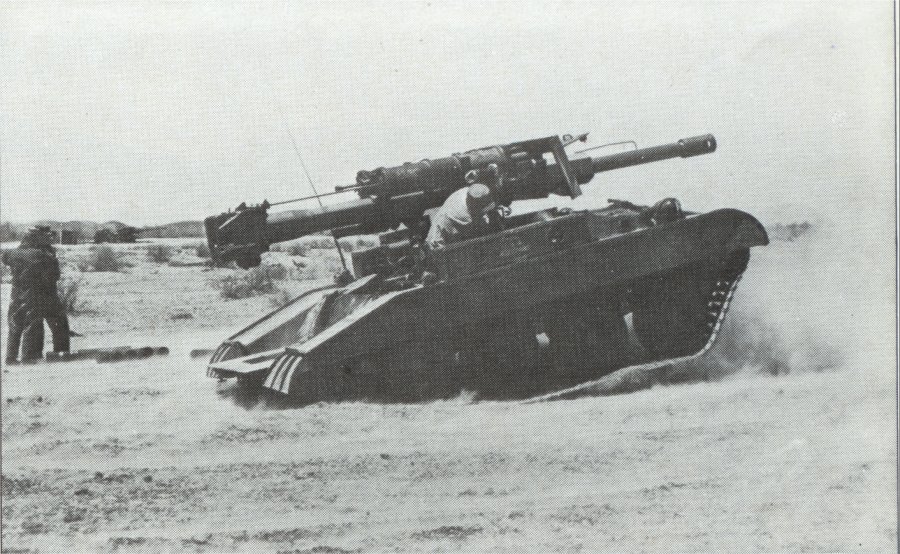

The three prototypes had the E36R1 installed inside an M1 Cupola – the machine gun armed cupolas found on the M48 and M60 tanks – with a coaxial machine gun. This cupola was then mounted over the commander’s position, with the fuel and pressure systems installed in the personnel compartment. Initially, the coaxial machine gun consisted of the .50 Cal (12.7mm) M85, this was later changed to the .30 Cal (7.62mm) M73.

Testing of the prototypes took place in 1961 at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Fort Greely, Alaska. In March 1962, the E31R1-E36R1 was standardized by the Chemical Corps Technical Committee (CCTC) as the M10-8. This nomenclature denoted the M10 fuel and pressure unit, and the M8 flame gun or ‘Cupola Group’. A year later, in 1963, the United States Army Materiel Command (AMC) officially type-classified the vehicle as the Self-Propelled Flame Thrower M132. In December of 1963, a new Diesel powered version of the M113 was nearing the end of its development, this would become the M113A1. The natural progression for the M132 was for it to be built on the hull of the new M113A1. The new version was classified by the AMC as the M132A1. The M132A1 was also known as the ‘Standard A’ with the earlier M132 version known as the ‘Standard B’.

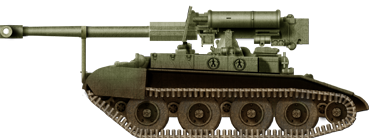

Overview of The M132

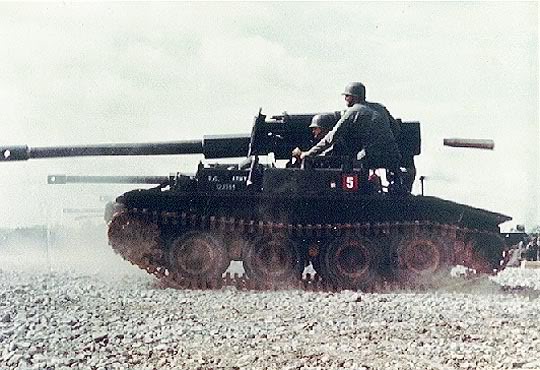

In total, the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) would produce 351 vehicles, consisting of 201 M132s, and 150 M132A1s. The M132 was operated by a two-man crew consisting of the driver, front and left, and the flame gunner/commander, located behind the driver in the center with the flame gun. Overall, the dimensions of the M113 chassis were unchanged. It remained 15 feet 11 ½ inches (4.8 meters) long and 8 feet 9 ¾ inches (2.6 meters) wide. Due to the flame cupola, it is 2 ¼ inches shorter than the standard M113 at 7 feet 11 ¾ inches (2.4 meters) in height. This is due to the lack of a mount for a machine gun. The M132 retained the M113’s top speed of 42 mph (68 km/h).

Flame Equipment

In the cupola, the M8 flame projector is mounted on the left with the coaxial M73 .30 Cal (7.62 mm) machine gun on the right. The barrel of the projector is flat with a sausage-like aperture. The cupola is traversed by hand and has a 360-degree arc of rotation. Both the machine gun and flame gun share a vertical traverse of +55 to -15 degrees. The cupola was equipped with 4 vision blocks and an M28D sight for the flame gunner/commander.

The flame gun is fed by the M10 fuel and pressure unit, located in the rear of the vehicle in what would be the personnel bay of the standard M113. The drop ramp was retained on the M132 to allow easy access and refueling to the weapon systems. The M10 unit took the form of four snowman-like structures, consisting of a large, spherical 50 gallon (227 liters) pressurized fuel tank with a smaller, spherical compressed air tank on top. The fuel tanks were pressurized to 325 pounds per square inch (23 kg/cm²), with the air tanks pressurized to 3,000 pounds per square inch (210 kg/cm²). The fuel tanks are connected in series, with the last one connected to the rotating joint of the cupola group. The air tanks are also connected together and provide pressure for the flame gun and fuel tanks. The tanks were placed in a removal rack system to allow easy maintenance for both the tank system and the internal components of the vehicle.

In total, the M132 could carry 200 gallons (909 liters, *the dropped M59 version could hold 400 gallons/1818 liters) of thickened, gasoline-based flame fuel. This fuel could be propelled to ranges of 12 to 218 yards (11 to 200 meters).

Service

Where its bigger brother, the M67, found service almost exclusively with the United States Marine Corps (USMC), the M132 would enter service with the US Army, specifically in Armored Cavalry units. Based on ensuing combat experiences, the Army Concept Team in Vietnam (ACTIV) advised that four M132s and two regular M113s be attached to each regiment. Headquarter companies of U.S. Armor and Cavalry units were all assigned at least one M132. Also, armored regiments of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN, Viet: Lục quân Việt Nam Cộng hòa) were all assigned four M132s. The M132s were not limited to the US Army, however. Specific tactics were drawn up for operations with both the Army and Marine Corps, but also for the Navy.

Standard combat procedure for the M132 was thus: 1) the M132 would advance on a target, using the coaxial M73 machine gun to suppress the target. 2) continuing to fire, the vehicle will move into flamethrower range of the target. 3) the flame gun is fired. In some instances, this may first consist of a “wet burst” of unlit fuel, which would then be ignited by a second ignited burst. The “wet burst” method had been in use since the Second World War. Flame tanks, whether it be the Churchill Crocodile or POA-CWS H1 Sherman, would fire unlit fuel at defensive positions, allowing it to ‘soak’ into the structure. The second lit burst would then ignite the first burst, burning out the defenders. Due to the location of the flame gun behind the driver’s position, it was recommended that the driver keep his hatch closed in combat, for obvious reasons.

Due to the vehicle’s thin, aluminum armor, it was relegated to a strictly support role, operating only with the protection of infantry or armored support. Even so, the vehicle was a valuable asset to convoys. It served as protection against hidden attackers in the heavily vegetated roadsides of the Vietnamese jungle. There is also a recorded example of an M132 knocking out a Vietcong 57mm recoilless rifle team with a 3-second flame burst during the Battle of Ap Tau O in 1966.

Unfortunately, not too much more is known about individual battles or skirmishes the M132 may have taken part in. The Vietnam War would be the only conflict that the M132 saw service in. The small paragraph below from the US Army report ‘Mechanized and Combat Operations in Vietnam’ published in March 1967, gives a little detail on the vehicle’s use in the conflict:

The M132 mechanized flame thrower has been successfully employed in offensive and defensive operations in Vietnam. In search and destroy operations, they are normally employed in pairs against bunkers and densely foliaged enemy-defended areas containing antipersonnel mines and booby traps. Flame directed at such areas may not destroy a protected enemy, but heat detonates mines and defoliates the area. In defensive positions, the flamethrower is employed to fill gaps not covered by direct fire weapons and to illuminate the area. During movements, the M132s can provide close-in flank protection to the column…

When being used in Naval operations, M132s would be backed onto Armored Troop Carriers (ATC, converted LCM-6 vehicle carriers) accompanied by a 2 ½ ton refueling truck. The M132s would fire over the sides of the vessel at targets on the river bank. There is at least one recorded example of this taking place on the Mekong River.

An Unquenchable Thirst

In operations, the M132 was accompanied by a specially adapted variant of the M548 Cargo Carrier. This was the Flame Thrower Service Vehicle XM45E1. As the M132 had such a small flame fuel capacity, it had a short burn time of just 32 seconds (*the dropped M59 version had a 70 second firing time). The XM45E1 was designed as a refueler for mechanized flamethrowers. The vehicle could mix and transfer thickened flame fuel. It also had an air-compressor to replenish air tanks and carried spare flame system parts. As well as the M132, the XM45E1 also supported the M67, but to a lesser extent.

Fate

The M132 was a successful vehicle. Modified versions of its M10 flame turret even went on to be used on some smaller naval vessels. Despite its success, the M132 would share the same fate as the M67 Flame Tank, being one of the last mechanized flamethrowers to serve with the US Military. The M132 and M67 would be completely phased out by the early 1980s, by which point the controversial weapons had largely fallen out of favor in many of the world’s militaries due to humanitarian reasons. Flamethrowers were controversial with the operators as well as those on the receiving end. They were dangerous to use and the injuries caused by them were horrific. The United States officially stopped using all flamethrower types in 1978 and continued to phase them out after that date. The reason stated at the time was: “flamethrowers were not effective in modern combat scenarios”.

A few M132s survive to this day. One can be found in Vietnam at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon). One of the only surviving examples in the US can be found at the United States Army Chemical Corps Museum at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

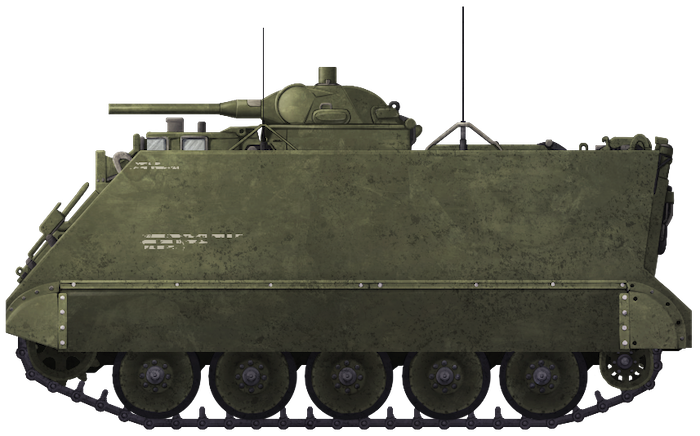

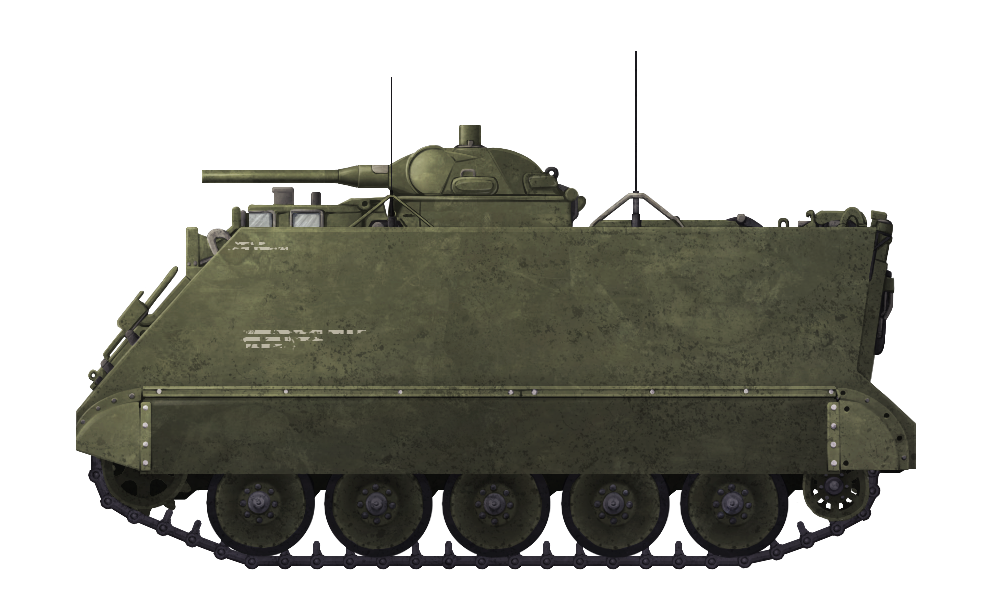

Illustration of the Self-Propelled Flame Thrower M132 ‘Zippo’, produced by Andrei ‘Octo10’ Kirushkin, funded by our Patreon campaign

M113 APC specifications |

|

| Dimensions (L-w-H) | 4.86 x 2.68 x 2.50 m (15.11 x 8.97 x 8.2 ft) |

| Total weight, battle ready | 12.3 tonnes (24,600 lbs) |

| Crew | 2 (Commander/Gunner, Driver) |

| Propulsion | Detroit 6V53T, 6-cyl. diesel 275 hp (205 kW) P/w 22.36 hp/tonne |

| Transmission | Allison TX-100-1 3-speed automatic |

| Maximum speed | 42 mph (68 km/h) road/3.6 mph (5.8 kph) swimming |

| Suspensions | Torsion bars |

| Range | 300 miles/480 km |

| Armament | Main: M10-8 Flame thrower system. Sec: Coaxial M73 .30 Cal (7.62mm) Machine Gun |

| Armor | Aluminum alloy 12–38 mm (0.47–1.50 in) |

| Production | 351 |

Sources

R. P. Hunnicutt, Bradley: A History of American Fighting and Support Vehicles, Presidio Press

Michael Green, Images of War: Armoured Warfare in the Vietnam War, Pen & Sword Publishing

Captain John Ringquist, U.S. Army Flamethrower Vehicles Part 3, Army Chemical Review

Fred W. Crimson, U.S. Military Tracked Vehicles, Motorbooks International

Armored Fighting Vehicle Data Base

www.globalsecurity.org

www.revolvy.com