Spanish State (Late 1960s/Early 1970s)

Spanish State (Late 1960s/Early 1970s)

Armored Personnel Carrier – Paper Project

The BMR-600 has been a massive success for Spain and its military industrial complex. It achieved the decades-long ambition of domestically developing and producing armored vehicles to suit the country’s needs. In addition, it had some modest export success. Before the six-wheeled BMR-600, there was the VBTT-E4, a four-wheeled armored car envisioned nearly a decade earlier. Like the BMR-600, it was designed with variants to fulfill the different roles in mind. However, unlike the BMR-600, it never left the drawing board.

Context – From Isolation to the Spanish Economic Miracle

Following his victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), General Franco went on to rule Spain for three and a half decades with an iron fist. The conflict had devastated the country, destroying agricultural production and the already limited industrial capacity. The human cost had been immense. Mass famine and political persecution in the post-war years further diminished the population and the prospects of the people.

To make matters worse, for its open support of the Axis powers during part of the Second World War, Spain was isolated by the Allied powers and was excluded from the Marshall Plan and the United Nations. The Spanish State imposed a policy of economic autarky with disastrous effects.

The new geopolitical situation created by the Cold War was to change Spain’s destiny. Given the country’s strategic location at the mouth of the Mediterranean and Franco’s vehement anti-Communism, the US saw Spain as a new key ally. In 1953, this new relationship was cemented in the Madrid Pact. The economic policy of autarky was abandoned in the late 1950s, as widespread change to the regime was adopted, and technocrats were given positions of power.

During the 1960s, the technocratic government reversed the situation, giving rise to the ‘Spanish economic miracle’. Between 1960 and 1973, the Spanish economy grew at an average of 7% each year. In this same period, industry grew at an annual average of 10%, as Spain moved from an agricultural to an industrial economy and society. The economic miracle also owed a lot to the growth of tourism, which to this day remains one of Spain’s economic motors. In 1960, there were 6 million foreign tourists, and just over a decade later, in 1973, there were 34 million.

The Military Context at Home and Abroad

Spain had successfully managed to modernize its armed forces with the large influx of US vehicles that had arrived as a result of the Madrid Pact. Between 1953 and 1970, Spain received: 31 M24 Chaffees, 42 M4 High-Speed Tractors, 84 M5 High-Speed Tractors, 24 M74s, over 166 M-series half-tracks, 411 M47s, 12 M44s, 28 M37s, 72 M41 Walker Bulldogs, 6 M52s, 16 LVT-4s, 54 M48s, 171 M113-based vehicles, 5 M56s, and 18 M578s.

In spite of this, Spain was not fully able to completely prepare for the kind of mechanized warfare that had emerged during the Second World War and which had become consolidated in the early Cold War years. Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs) were tested towards the end of the Second World War and would appear in large numbers during and after the Korean War. APCs were, and are, able to transport an infantry squad in the relative safety of an armored hull. In some instances, these vehicles also carry armament of their own to support the infantry dismounts.

Spain had the M-series half-tracks and the fully-tracked M113-based vehicles to perform these roles to different extents, but lacked the wheeled counterparts which would enable an even more rapid deployment of troops and quicker support across the battlefield.

Early armored cars could more accurately be described as armored personnel carriers. In fact, the majority of Spain’s first armored cars, the Schnerider-Brilliè, the Camiones Blindados Modelo 1921, and the myriad of tiznaos of the first year and a half of the Spanish Civil War accurately fit this description. Their main purpose was to provide protection for an infantry component carried inside, who could fire their rifles and machine guns from within. Some were equipped with machine gun turrets.

Whilst there were certainly earlier examples of ‘modern’ wheeled APCs more akin to their tracked counterparts during the Second World War, such as the BA-64E, the concept really took off in the 1950s and 1960s. The first mass-produced examples were the Soviet 4-wheeled BTR-40 and 6-wheeled BTR-152, both introduced in 1950. These were followed in the Soviet Union by the 8-wheeled BTR-60 in 1961. Outside the Soviet Union, one of the first examples was the 6-wheeled British Alvis Saracen, first introduced in 1962.

The concept of wheeled APCs was further expanded by the introduction of the 4-wheeled Cadillac Gage Commando and MOWAG Roland in the early 1960s. Portugal, Spain’s neighbor, produced an unlicensed copy of the Cadillac Gage Commando, the Bravia Chaimite, in 1967.

Based on the drawings alone, it seems as though the Spanish company INCOTSA was aiming to follow a similar route with the VBTT-E4. Like the Cadillac Gage Commando and the Bravia Chaimite, the VBTT-E4 was to have a number of derivatives or variants to carry out different tasks, such as mortar carrier or tank destroyer. It is not entirely clear why the VBTT-E4 was conceived nor how Spanish military authorities reacted to it, but what is clear is that it never went into production.

INCOTSA

Almost nothing is known about Internacional de Comercio y Tránsito S.A. (INCOTSA) [Eng. Commerce and Transit International Limited Company], the company that designed what was to be the VBTT-E4.

According to Spanish military historians Jose Mª Manrique García and Lucas Molina Franco, in the early 1960s, INCOTSA collaborated with Material y Construcciones S.A. (MACOSA) [Eng. Material and Constructions Limited Company], which specialized in manufacturing railway rolling-stock, to design two vehicles. One was the Vehículo Blindado de Combate de Infantería VBCI-E General Yagüe, an armored personnel carrier/infantry fighting vehicle. The other was the Vehículo Blindado de Reconocimiento de Caballería VBRC-1E General Monasterio, a cavalry reconnaissance vehicle. Their fellow historians, Francisco Marín Gutiérrez and José Mª Mata Duaso, on the other hand, make no mention of INCOTSA’s involvement. Regardless, neither vehicle gained the Spanish military’s attention.

Name

The name VBTT-E4 is an acronym. ‘VBTT’ stands for Vehículo Blindado de Transporte Táctico [Eng. Armored Vehicle for Tactical Transport], defining its role. Neither the original drawings nor secondary sources clarify what the ‘E’ stands for, but it could well stand for Español [Eng. Spanish] or experimental. The ‘4’ could simply indicate the number of wheels on the vehicle.

Design

Appearance and Dimensions

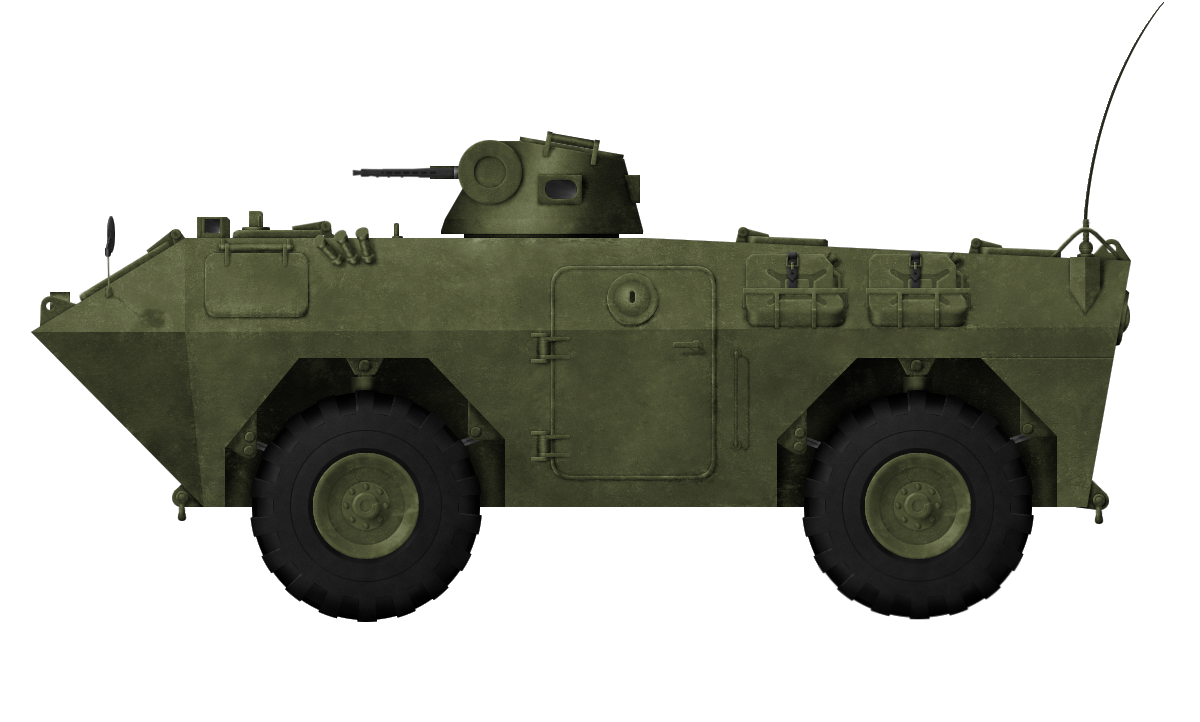

Based on the design drawings, the VBTT-E4 would have had quite a similar appearance to the Cadillac Gage Commando and the Bravia Chaimite. The vehicle would have been 5.4 m long from the front peak to rear. The space between the center of the front and rear wheels on either side would have been 2.7 m. The distance between the frontal peak and the center of the first wheel would have been 1.65 m and 1.05 m between the center of the rear wheel and the rearmost point of the VBTT-E4. Excluding the turret, the VBTT-E4 would have been 1.85 m tall and, when fitted with the 45 cm high turret, 2.3 m. Width would have been 2.44 m. These dimensions would have made the VBTT-E4 shorter than its American and Portuguese counterparts, but wider.

| Comparison of dimensions between VBTT-E4, V-100, and Bravia Chaimite | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| VBTT-E4 | Cadillac Gage Commando V-100 | Bravia Chaimite | |

| Length (m) | 5.40 | 5.69 | 5.60 |

| Height (m) | 2.30 | 2.40 | 2.39 |

| Width (m) | 2.44 | 2.26 | 2.26 |

The design drawings show an angled front, perhaps intended as a wave breaker. Two hatches on either side of the upper-plate would have provided the crew inside with visibility. Between them there would have been a grille for the engine. This was almost exactly replicated on the front top of the vehicle, with two hatches on either side of a large hatch giving access to the engine. Additional hatches on either side of the front would have afforded the crew a lateral view. The turret would have been in the top middle of the VBTT-E4. Positioned almost exactly in the middle half and opening towards the front, the main doors for entry and exit would have offered some potential protection to infantry exiting the vehicle in a combat situation. On the rear left side, there would have been stowage space, whilst the engine exhaust would have been on the right. Three hatches would have allowed entry and exit in the rear half of the roof, along with two pickaxes and two spades. Two additional outwards-opening doors would have been situated at the very rear.

Armor and Protection

Armor would have been between 8 mm and 12 mm thick, with the thickest armor at the front and around key components and thinnest around the rest of the vehicle. Manrique García and Molina Franco indicate that the VBTT-E4 would have weighed a mere 2.3 tonnes. This estimation seems far too light, and is perhaps a typo, as the more lightly armored and slightly larger Bravia Chaimite was over 6.8 tonnes and the Cadillac Gage Commando V-100 7.37 tonnes. Marín Gutiérrez and Mata Duaso suggest a more realistic 8.5 tonnes fully loaded and 7.5 tonnes empty.

A set of three smoke dischargers would have been placed on the sides of the hull, around the same length as the first set of wheels.

Turret

The VBTT-E4’s cylindrical turret would have been 45 cm tall, the front part being taller than the rear. It would have had glass-protected vision slits in the front middle, off-center on either side, and at the center rear. Entry and exit would have been through a two-part hatch at the rear of the turret.

Armament

The main armament on the VBTT-E4 would have been a 7.92 mm German MG 42 machine gun placed on the left of the turret. Its depression/elevation would have been -8º to 55º.

The MG 42 was one of the most successful machine guns of the Second World War. Its main characteristic was its incredibly high rate of fire, around 1,200 rpm. After the Second World War, many nations copied its design, and examples of the machine gun have survived in service until the 21st century.

It was an air-cooled, belt-fed, open-bolt, recoil-operated machine gun. Its quick change barrel meant it was largely unsuitable for use on armored vehicles, making it an odd option for the VBTT-E4. Spain had only received a limited number of MG 42s during the Second World War and had no way of acquiring more, also making it a questionable choice. Had the vehicle been built, it may have been armed with a different machine gun. All things considered, some of the early BMR-600 prototypes had an externally mounted MG 42.

The VBTT-E4 would have also had a 40 mm grenade launcher on the right side of the turret. This armament’s depression and elevation is not marked in the drawings. This was an interesting design choice, as at the time, Spain had very little experience with using these weapons, especially in the turret of an armored vehicle. The available sources do not specify the exact model. The M75 Grenade Launcher and the Mk 18 Mod O Grenade Launcher were two American 40 mm grenade launchers of the era. Used in helicopters and on patrol boats, they would most likely have been too big for the VBTT-E4’s small turret.

The weapon selected might not have been a grenade launcher, but instead, a gun-mortar, such as the French Brandt Mle CM60A1. A gun-mortar is a hybrid weapon capable of engaging area targets with indirect high-angle fire and also specific targets, such as vehicles and bunkers, with direct fire. Around the same time the VBTT was designed, Spain acquired nearly a hundred Panhard AML-60s armed with the Brandt Mle CM60A1. Perhaps this kind of configuration is what INCOTSA’s designers had in mind.

Running Gear and Engine

The VBTT-E4 would have had four-wheel drive with four large 13,00×20-sized thick-tired wheels.

The engine would have occupied from the front central part of the VBTT-E4 to the mid-part of the vehicle.

The VBTT-E4 would have been powered by a 6 cylinder diesel Pegaso 9100/40 engine producing 170 hp at 2,000 rpm. Pegaso, one the brand names of Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones Sociedad Anónima (ENASA) [Eng. National Truck Limited Company], specialized in trucks, but it would go on to produce the BMR-600 armored cars and VEC cavalry vehicles for the Spanish Army in the 1980s.

The Pegaso 9100 engine was marketed as powerful, reliable, small, light (625 kg), and easy to maintain.

The engine would have been connected to an ENASA gearbox with six forward gears and one reverse.

The sources put the maximum speed of the VBTT-E4 at 85 km/h and the maximum range 1,100 km. This would have made it slower than the Cadillac Gage Commando V100 and the Bravia Chaimite, but with more range.

| Comparison of engines between VBTT-E4, V-100, and Chaimite | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| VBTT-E4 | Cadillac Gage Commando V-100 | Bravia Chaimite | |

| Engine | Pegaso 9100/40 | Chrysler 361 | Cummins |

| Fuel type | diesel | petrol | diesel |

| Horsepower (hp) | 170 | 210 | 155 |

| Rotations per minute (rpm) | 2,000 | 4,000 | 3,300 |

| Maximum speed (km/h) | 85 | 100 | 99 |

| Maximum range (km) | 1,100 | 644 | 804 |

Crew and Infantry Dismounts

It is thought that the VBTT-E4 would have carried 12 personnel, composed of 2 crewmembers (a driver and a commander), and up to 10 infantry dismounts.

The driver would have sat on the left side and the commander on the right, with the engine sandwiched between them.

Eight of the infantry dismounts, four on either side, would have been placed inside the main compartment in the center of the vehicle, on foldable seats. They would have used the side doors to enter and exit the vehicle. The remaining two infantry dismounts would have been placed at the rear and would have entered and exited the vehicle that way. This arrangement seems rather impractical, as the two rear positioned infantry dismounts would have been largely separate from the rest of the squad. The eight infantry dismounts in the center would have been exposed to enemy fire if they had to exit the vehicle in a combat situation.

In the available drawings, nobody is occupying the turret seat. This space would most probably have been occupied by a gunner or, alternatively, the commander. An additional crewmember to the right of the engine could have been a radio operator.

Assessment

Seemingly inspired by a tried and tested design, the VBTT-E4, had it been built, would have been a competent and relatively fast vehicle. It certainly would have provided the Spanish armored forces with a type of vehicle they lacked.

Nevertheless, close inspection of the VBTT-E4’s drawings point to the INCOTSA’s design team’s inexperience. The armament options were curious. The MG 42 was not designed to fit into the turret of armored vehicles and the 40 mm grenade launcher or mortar was of questionable value. Furthermore, both would necessarily have been operated by a single crewmember in the restricted confines of the turret. The drawings make no allowance for an ammunition load inside the limited space of the vehicle. Two different armaments needing different ammunition would have complicated matters further.

The proposed separation of the infantry dismounts inside the VBTT-E4 was impractical. Two infantry dismounts exiting large doors at the rear and eight infantry dismounts using smaller doors in the middle was not a wise design choice. With more consideration, the internal arrangement of the vehicle could probably have been improved, even if this meant reducing the number of infantry dismounts.

Variants

INCOTSA’s design team also proposed five variants of the VBTT-E4 to fulfill different roles.

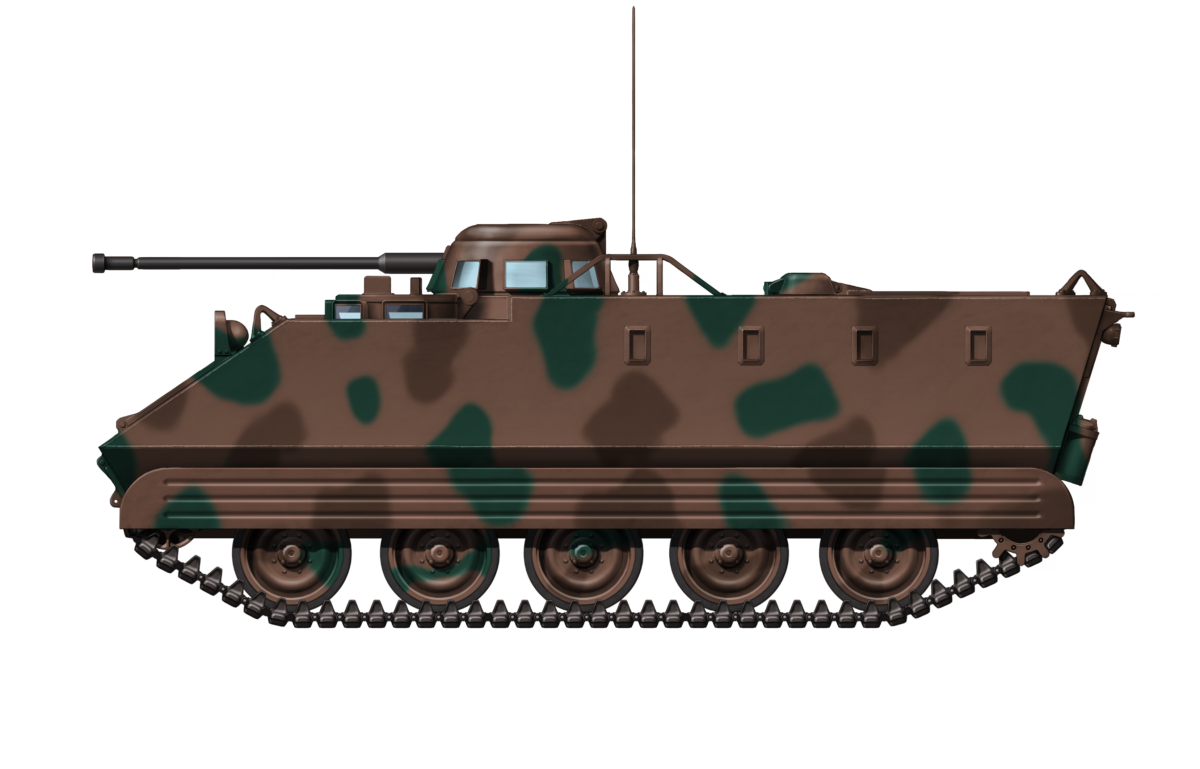

VBTT-E4 Portamortero

The VBTT-E4 Portamortero [Eng. Mortar Carrier] was a variant which would have reorganized the interior of the vehicle to carry an unspecified mortar. It is easy to assume this would have either been the 81 mm Ecia modelo 1951 or the 81 mm Ecia modelo L. The latter was used on the later mortar-carrying BMR-600 version.

The rear of the roof would have had a large circular hatch cut in it to allow the firing of the mortar. The rear would have seen the most modifications.

The infantry dismounts would have been replaced by a crew of three with plenty of space to operate the 81 mm mortar. This variant was probably the one that resembled the regular VBTT-E4 the most.

VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW)

In the 1980s, Spain armed some of its BMR-600s and M113s with a BGM-71 TOW anti-tank missile launcher. It appears that INCOTSA had anticipated this with the VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW) [Eng. Anti-tank]. Given that the BGM-71 TOW anti-tank missile only entered service in 1970, it is an educated guess that the whole VBTT-E4 project was actually conceived in the early 1970s, rather than the late 1960s, as some sources suggest.

As on the VBTT-E4 portamoteros, the VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW)’s rear and interior would have undergone the most changes. The TOW launcher would have been housed in the right rear side of the vehicle. The drawings suggest it was to have been kept inside the vehicle most of the time and only taken out when in use. In this way, it would have differed from the BMR-600 and M113 variants. It would seem that the VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW) would not have had a full 360º of fire. It is unknown how many crewmembers would have been needed to operate the weapon.

The VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW) would have been the only VBTT-E4 variant without a turret. Even so, at 2.9 m high, it would have been the tallest of all the VBTT-E4 variants.

VBTT-E4 de Recuperación

The VBTT-E4 de Recuperación [Eng. Recovery] would have been the recovery and engineer version of the VBTT-E4. For the most part, externally, the vehicle would have remained much the same as other versions, even keeping the turret.

A small crane would have been added at the front. Estimated lifting capacity is not given in the sources, but it would most likely have been low. In the middle of the front hull there would have been a winch, once more, probably with a low towing capacity. Additionally, a bulldozer blade would have been attached to the front to stabilize the vehicle when the crane was in use and to shift earth to create trenches.

Details regarding the interior are sketchy, but it seems that the front part would have been reworked to accommodate the mechanical components of the crane and bulldozer blade. Even so, the drawings show the two frontal crew positions. Inside, the infantry dismount squad would have been replaced with an engineer component or a small portable workshop.

VBTT-E4 de Exploración y Combate

The most ambitious and different VBTT-E4 version was to have been the VBTT-E4 de Exploración y Combate [Eng. Reconnaissance and Combat]. Large parts of the vehicle would have been reworked. For instance, the engine would have been moved to the back and the whole rear side of the VBTT-E4 would have needed to be reworked to accommodate it. There would have been no rear entry and exit doors. Consequently, there would have been no infantry dismounts onboard either.

The front of the vehicle would have required significant reworking. A large hatch would have been added where the engine ventilation grilles would have been on the regular VBTT-E4. As the frontal-placed engine would have been installed in the back, the frontal crew would have been repositioned. Instead of being placed on either side of the engine, one, most likely the driver, would have been placed in the center, with the other crew position remaining on the right.

Perhaps the most significant change would have been the new turret. Its similarity to the H-90 turret on the Panhard AML suggests that it would have been the same turret, as Spain had acquired 100 AML-90s in 1965. In fact, in the 1980s, as the final turret and armament for the VEC were being decided, H-90 turrets from out-of-service AML-90s were used as a temporary measure.

The gun would have been a 90 mm gun. Following the logic that the VBTT-E4 de Exploración y Combate would have used the H-90 turret, the gun could have been the low-pressure 90 mm D921/GIAT F1. Nonetheless, the vehicle’s chassis may well have suffered significantly from the gun’s recoil. The gun would have had 15º of elevation and no depression, making it rather limited. No machine gun is shown in the drawings.

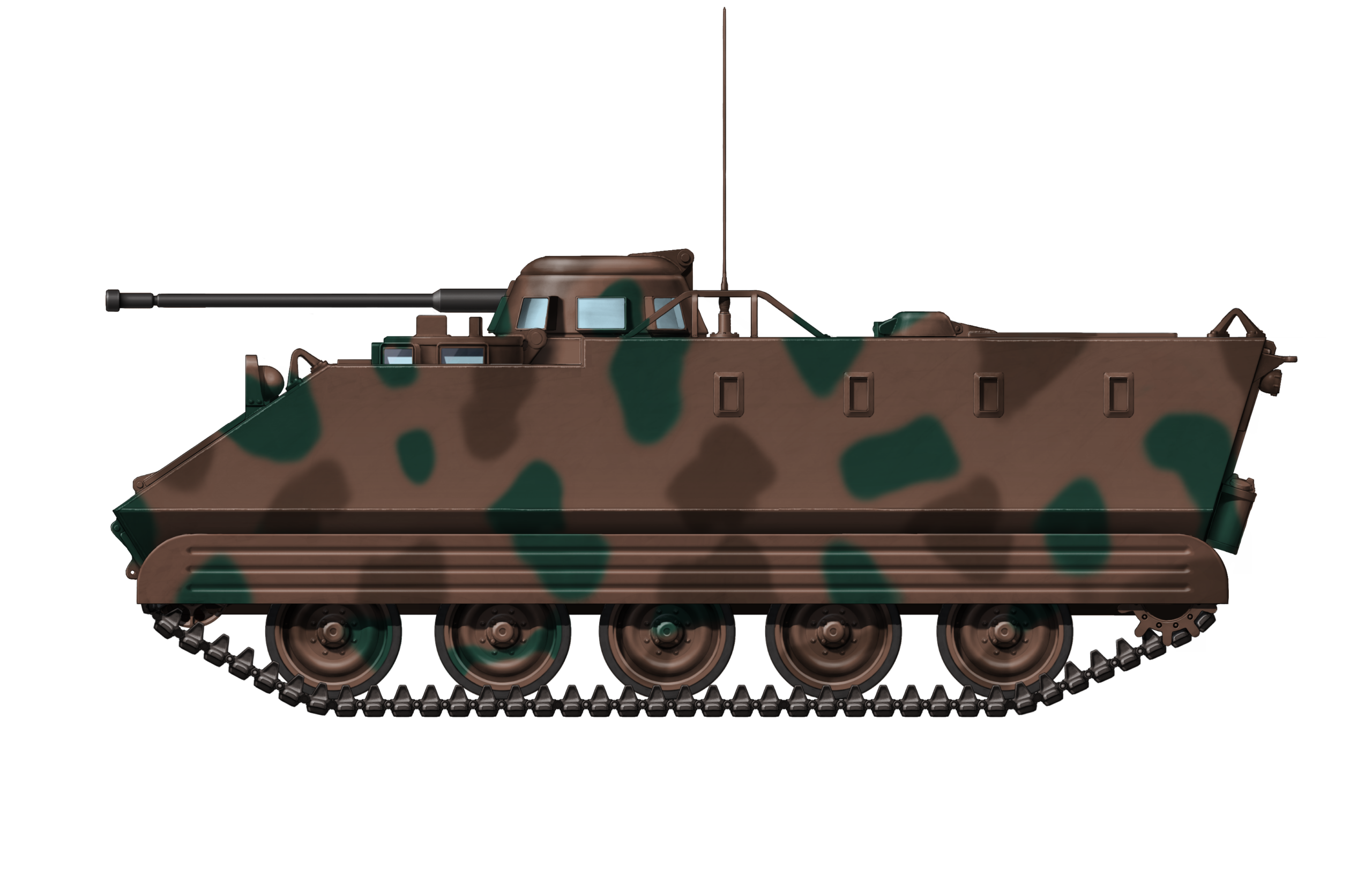

VBTT-E4 de Apoyo

The least well known VBTT-E4 variant is the VBTT-E4 de Apoyo [Eng. Support]. Its purpose would have been to provide support to infantry units. This variant would have undergone the same changes to the hull as the VBTT-E4 Exploración y Combate.

The differentiating factor would have been its unique turret and gun. Although not specified in the sources, the gun in all probability would have been a 20 mm autocannon of some description. Gun depression would have been -7º, whereas an elevation of 70º would have enabled firing at air targets.

The BMR-600

The VBTT-E4 proved unsuccessful, but, less than a decade later, work began on what would eventually lead up to the BMR-600, or Blindado Medio sobre Ruedas. The BMR-600 would be larger, better armored, and six-wheeled.

There is no clear evidence as to the influence of the VBTT-E4 on the BMR-600. There are some visual similarities between the two designs, but these just may be a coincidence.

Since being introduced in 1979, around a thousand BMRs in all variants have been produced and some have even been exported to countries such as Egypt, Peru, and Saudi Arabia. The BMR variants which have been introduced into service have included mortar carriers, anti-tank missile launchers, recovery, and cavalry reconnaissance, among many others.

The Spanish BMR fleet was modernized in the early 1990s and has seen service with Spanish peacekeeping missions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the former Yugoslavia. However, its future is in doubt and it is expected that it will be replaced by the VCR 8×8 Dragón over the next decade.

Conclusion

The VBTT-E4 is a curious project. There is no conclusive evidence as to why it was conceived nor why INCOTSA became involved. Neither is it known if it was actually presented to the Spanish military and what was thought about it.

The VBTT-E4 certainly fitted in with the military thinking at the time. Spain wanted a wheeled APC which could also provide some support to its infantry dismounts. Spain would end up choosing the 6×6 BMR-600, not the 4×4 VBTT-E4.

The VBTT-E4 had some undoubtedly sound design components but the choice of armament and the positions for the infantry dismounts inside the vehicle left much room for improvement.

INCOTSA envisioned a family of vehicles on the basis of the VBTT-E4. These would have provided a great deal of flexibility. On the other hand, some of these variants demonstrated INCOTSA’s inexperience when it came to design choices.

Estimated Specifications of VBTT-E4 and Variants |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBTT-E4 | VBTT-E4 Portamortero | VBTT-E4 Contracarro (TOW) | VBTT-E4 de Recuperación | VBTT-E4 de Exploración y Combate | VBTT-E4 de Apoyo | |

| Length (m) | 5.4 | ~5.6 | ~5.9 | ~5.7 | ||

| Width (m) | 2.44 | |||||

| Height (m) | 2.3 | 2.9 | ~2.4 | ~2.35 | ||

| Weight (tonnes) | 8.5 | +8.5 | ? | |||

| Engine | 170 hp Pegaso 9100/40 diesel | |||||

| Speed (km/h) | 85 km/h | |||||

| Range (km) | 1,100 | |||||

| Main armament | 7.62 mm MG 42 | 81 mm mortar | TOW launcher | None | 90 mm gun | 20 mm autocannon |

| Secondary armament | 40 mm grenade launcher | None | ||||

| Crew | 2-3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3-4 |

| Infantry Dismounts | 10 | None | ? | None | ||

Sources

Francisco Marín Gutiérrez & José Mª Mata Duaso, Carros de Combate y Vehículos de Cadenas del Ejército Español: Un Siglo de Historia (Vol. III) (Valladolid: Quirón Ediciones, 2007)

Francisco Marín Gutiérrez & José María Mata Duaso, Los Medios Blindados de Ruedas en España. Un Siglo de Historia (Vol. II) (Valladolid: Quirón Ediciones, 2003)

John McDonald and Richard Lathrop, Cadillac Gage V-100 Commando, 1960–1971 (London: Osprey Publishing, 2002)

José Mª Manrique García & Lucas Molina Franco, BMR Los Blindados del Ejército Español (Valladolid: Galland Books, 2008)

Pegaso Motor Diesel tipo 9100 170 CV manual