Soviet Union/German Reich (1932)

Soviet Union/German Reich (1932)

Superheavy Tank – None Built

In armored terms, few tanks evoke more awe in terms of size and specifications than the Maus, a 200-tonne behemoth from the tank-stable of the even more famous Dr. Porsche. It is also no secret that there is a certain following, especially online and in the media generally, for what could, at best, be described as ‘Nazi Wonder Weapons’. It is not that any one of these ideas could have won the war for Germany, that was simply not going to happen in 1945 regardless of whatever vehicle, missile, or plane the Germans developed. What they were, however, is a reflection of the giant level of engineering and imagineering which ran amock at times in Nazi Germany. A political mindset wanting a 1,000 year Reich was also thinking huge in every conceivable area, from giant planes to super-ships, rockets, and, of course, tanks. If the Maus impressed as a 200-tonne vehicle, then imagine a vehicle 5-times that weight; a true goliath.

Online, that vehicle has become known as the ‘Ratte’ (Eng: Rat), as some kind of allusion to its Maus-sized forebear, but the vehicle was less rat-sized and more landship-sized and was known under the less amusing name of ‘P.1000’. Perhaps even more surprising than its incredible weight and size was that this vehicle was not some late-war attempt to wrestle victory from defeat by overwhelming Allied superiority, but began life in the 1930s. More than that, it did not even begin life in Germany, but in the nation to become Nazi Germany’s greatest enemy, the Soviet Union.

The Men Behind the Tank

The primary figure in the story of the P.1000 is the enigmatic Edward F. Grote. (Note that his name is repeated numerous times online and in books as ‘Grotte’, but is very clearly written as Grote with one ‘t’ in both British and German patents, so his name assuredly was ‘Grote’). Grote’s work on huge tanks had begun early during the time he spent working in the Soviet Union (USSR). A skilled engineer, Grote had lived in Leipzig between 1920 and 1922, running an engineering concern where he had received several patents for engines, in particular diesel engine innovations. These included methods of cooling and also lubricating those engines with oil under pressure. Grote’s interest in power transfer and diesel engines would be very useful when it came to designing large and heavy tanks.

The Soviets

The Soviets had, after April 1929, tried to emulate the French FCM Char 2C with a project of their own. They had tried to engage foreign engineers and designers and were interested in the ideas of Edward Grote. Grote’s skills led him, by 1931, to become head of the Soviet design team for this new giant tank, his firm having been selected over two rival firms in 1930, primarily for political reasons – Grote was a sympathizer of the Soviet government and one of his engineers was a member of the German Communist Party. His task for the Soviets was to develop a breakthrough tank able to match the French FCM Char 2C and the order for this work was dated 5th April 1930. At the time, the specifications for this breakthrough vehicle were perhaps somewhat unremarkable, with a weight of just 40 tonnes and armor not less than 20 mm thick.

A design bureau known as AWO-5 was set up in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) for him to conduct this work. By 22nd April 1930, just over two weeks since the task was officially set, the preliminary outline was ready. This design became the first in a series of ‘TG’ tanks – TG for ‘Tank Grote’.

The Soviet TG or TG-1 tank was designed with the involvement of Edward Grote.

In just over a year, the first prototype was ready for trials, but the novel track design was a particularly weak point of the design. Added to this was that the cost was excessive, to the extent that the BT-5, an 11.5-tonne tank with an armor of just 23 mm at best, was preferred instead – hardly suitable for a breakthrough role, although its speed would be useful for exploitation of a breakthrough.

Source: Craig Moore

More versions of the TG followed and it inevitably grew larger, heavier and more complex in doing so, with the sixth and final version presented in May 1932. By this time, the Soviets had seemingly grown weary of a project which was producing increasingly large and expensive tanks when there were alternatives available, such as emulating the British A1E1 Independent.

The result was that the Soviets turned from this German design to their own vehicle inspired by the British A1E1 and which was ready in 1933, in the form of the T-35A. At over 45 tonnes, this tank was large – nearly 10 m long, and was fitted with 5 turrets, although armor was just 30 mm at best.

Source: Wiki

The First Fortress Tank

Grote, however, had not given up on his increasingly large tank ideas. It is worth noting that the big size limiter for tanks is based around the size and weight which can be borne by roads, and especially railways. These limitations restrict the maximum width and height of the vehicle more than the length. This has historically resulted in some very long vehicles, as the designers of the vehicles struggle to provide the armor and automotive power within these strict limits.

Grote, and several designers before and since, have understood that, as soon as you step beyond these maximums, there is no point in a vehicle a little wider or a bit taller than could be carried by train. Indeed, the decision to go big from a design point of view is technically very freeing, as the dimensions can be made whatever they need to be to fulfill the role of the vehicle. If, like it was for Grote, the need was for a well-protected breakthrough tank with a lot of firepower, then freeing himself from those strict limits meant he could make a big tank to mount big guns. It would need a big engine or engines to power it but, again, there was effectively no limit on the volume into which the unit or units required to power the vehicle could fit.

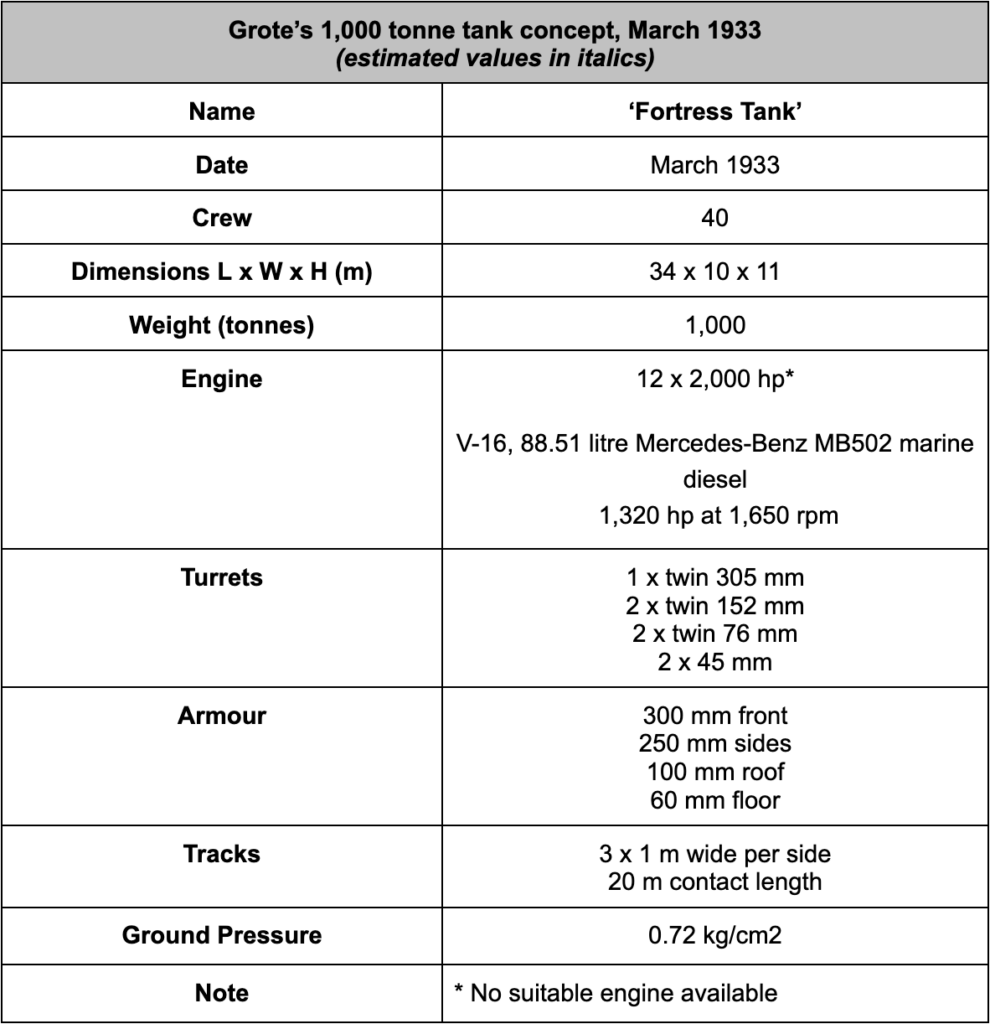

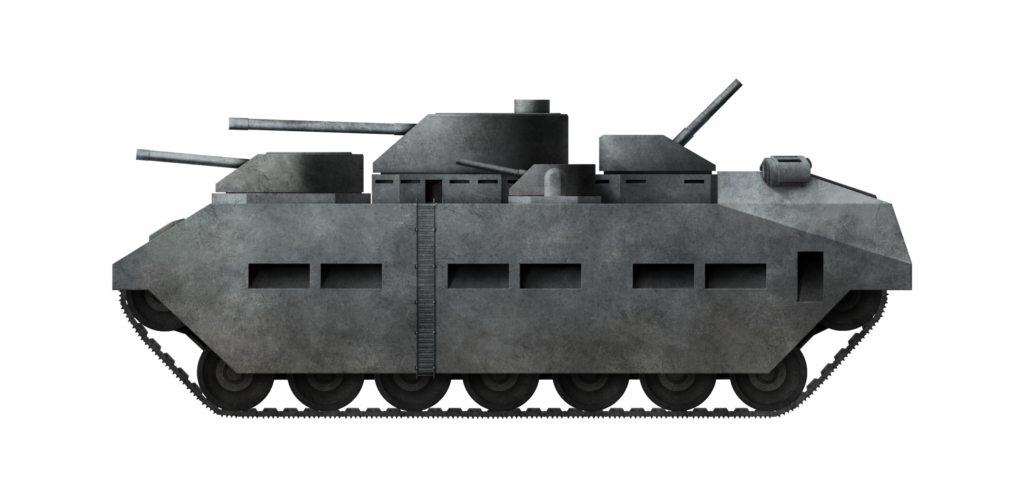

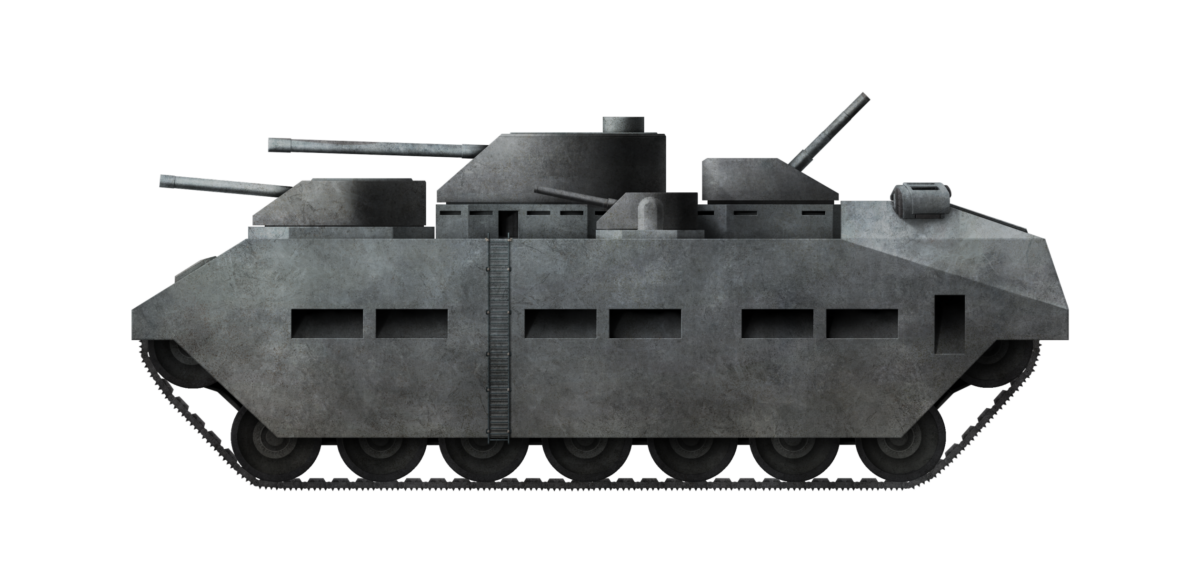

Liberated from the width and height restrictions of the rail gauge, Grote had gone beyond the plausibility of his TG vehicles and, in March 1933, submitted a new, massive, and less plausible vehicle concept to Soviet Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky. Tukhachevsky was a key figure in Soviet military modernization in the 1930s before he, like millions of others, fell victim to the murderous purges of Joseph Stalin. The dimensions of the vehicle were truly staggering. A hull 34 meters long, 10 meters wide, and 11 meters high, it was topped with a pair of 305 mm guns in fully rotating turrets. A pair of smaller turrets, each fitted with a pair of 152 mm guns, were mounted on the front corners of the hull, and two more turrets, each fitted with a pair of 76 mm guns, were fitted aft of the primary turrets. If that was not enough firepower, two further turrets, each fitted with a 45 mm gun, were also to be mounted.

The sides of the hull were vertical and used heavy armor plating 250 mm thick to cover the enormous road wheels* and suspension. The front of the tank was very well angled and was to be 300 mm thick. This 300 mm of armor was to be repeated on the front of the primary turrets and roof armor was to be 100 mm thick. Certainly, this would have been sorely needed given the size of the tank and what a target it would have made for enemy artillery or aircraft. The thinnest part of the armor was the hull floor, at 60 mm thick.

Supported on a trio of 1 m wide tracks on each side, there would be 6 m of track width on the ground. Given that the vehicle was estimated to weigh 1,000 tonnes, this track, with a ground contact length of 20 m, spread the great load and the ground pressure was calculated to be just 0.72 kg/cm2 (about half that of the 180 tonnes Pz.Kpfw. Maus), a little more than that exerted by a heavily laden man’s foot. This was truly the Festungs panzer or ‘Fortress’ type tank Grote was picturing, with a crew of not less than 40 men to command, drive, maintain and operate all of the weapons, but it was also no slouch despite its huge mass.

(* assuming the 1942 rebirth was just a revamped version of his 1933 idea, then the wheels would be around 2.5 m in diameter)

By virtue of twelve 2,000 hp 16-cylinder diesel engines (24,000 hp / 17,630 kW total) and a special hydraulic transmission, Grote expected his 1,000 tonne monster to manage up to 60 km/h. One of the crucial advantages the enormous size would give Grote would be the obstacle-crossing ability of the tank. With its high leading edge of track, his tank would be able to climb a vertical step no less than 4.8 m high and ford an 8 m deep river without having to concern itself with bridges.

With the design submitted, it was reviewed and found to have serious problems. Not the least of these was that the planned engine power and speed of the vehicle were not realistic. There was simply no engine producing 2,000 hp available. The V-16 (cylinders at a 50-degree angle) 88.51 liter Mercedes-Benz MB502 marine diesel engines, could, at best, produce just 1,320 hp at 1,650 rpm or a continuous output of 900 hp at 1,500 rpm. Assuming 12 of those could be used, then this would produce a continuous 10,800 hp or a maximum of 15,840 hp, well short of the 24,000 hp needed. The engines were to have been laid out 6 on each side and all driving a common driveshaft. This power was then to be transmitted either hydraulically or electrically to the drive sprocket.

Source: Pearce

A supercharged version of that engine was also available later, but this was not in production when Grote’s design was submitted. That engine, the MB-512, could produce the same continuous 900 hp as the MB-502 at 1,500 rpm, but an improved 1,600 hp maximum output at 1,650 rpm. Even if this improved version was available to Grote, it would, at best, have delivered just 19,200 hp combined maximum – just 80% of what he needed.

With no suitable engine available, the Soviets could not accept Grote’s design and would soon part company with Grote and embark on their own fortress-tank work. With the failure of the TG tanks and now this fortress tank, Grote’s work in the Soviet Union came to an end and he returned to Germany in 1933.

Back to Germany

Grote, now living in Berlin, did not stop his engineering and submitted another patent application in 1935. Several more patents followed, relating to transmissions and hydraulic couplings but also, and more importantly, for tracks as well.

Source: British Patent GB457908.

In January 1935, Grote filed a patent application for a novel type of caterpillar track. In his design, half of the metal links of a common style of track were to be replaced by intermediate links made of rubber sandwiched between the steel links. These rubber links would be in compression all the time, squashed between moving metal links on each side. The design would serve not only to create a lighter type of track but also one completely under tension the whole time, which would improve the efficiency of the driving force applied to the track. Perhaps more unusually, none of the links were actually physically connected together in the sense of a track pin. Instead, each track consisted of a pair of flexible chains, rather like the chain on a bicycle or chain saw, which would loop around the drive and road wheels. Each metal link would have two hollow channels made in it for each of these chains to pass through, and then, between each metal link, two of these smaller rubber intermediate links were placed, each with a single channel for the drive chain to pass through. The rectangular shape of the chain and of the channel in both the rubber intermediate links, and the metal links also prevented twisting of the links, or, in the case of the rubber links, any rotation from taking place. As the entire system was in compression the whole time, it also served to provide a completely sealed track system for the chain, so as to keep out dust, which would otherwise increase the wear and tear and reduce the track’s service life. Unlike a continuous rubber belt type track system, where damage means having to replace the whole length of track, this idea meant that localized repair was possible.

Source: German Patent DE651648

Another of his patents, submitted in 1936, was for a moveable caterpillar track system. In that invention, the leading edge of the track could be changed so as to be low during road movement or raised to climb obstacles. There is no mention of tank design in either the metal-rubber-metal track design patent or in the elevated track patent, so it might be assumed that there was no military element involved in his designs.

Source: German Patent DE632293.

Arguments with Burstyn

With some tank-related patents behind him, Grote saw himself referenced indirectly in a December 1936 magazine article that had stated that a German engineer had designed a 1,000-tonne tank for the Soviets. Grote chose to write his own piece in response defending the size of the vehicle he had designed and this appeared in the Kraftfahrkampftruppe magazine in 1937.

In doing so, Grote had managed to earn the ire of Günther Burstyn, the same Günther Burstyn who designed a tracked vehicle in 1912 and had tried, unsuccessfully, to get interest from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the idea. Burstyn was scathing in his own views on Grote’s concept, saying it was not only impractical due to its size, but also had no military utility, perhaps forgetting how naïve and impractical his own idea had been.

Source: Frohlich.

Source: yandex.ru

Source: Frohlich

Burstyn’s primary complaint was the weight of the vehicle based on the false assumption that more mass meant it would be immobile. The ground pressure for such a massive machine was not particularly great, as it was to have 6 sets of tracks, with each putting around 20 meters of track on the ground. With each track 1 meter wide, 6 of them, with 20 meters of length meant a track contact area of 120 m2 (20 m x 6.0 m) and producing a ground pressure of 0.72 kg/cm2, very low for a vehicle of its dimensions. For reference, the German Pz.Kpfw. VI Tiger produced around 1.04 kg/cm2

Further to this, Burstyn was also critical of the top speed. The desired top speed of 60 km/h was not possible with the engines available at the time but Burstyn did not claim it was impractical for that reason, instead, it appears to be based on the notion that big equals slow. Certainly, 60 km/h was not going to be possible even under the best of situations, as the engines required were lacking, but even assuming he could manage half of the required engine power, it is fair to assume Grote’s design would at least have matched the comparatively slug-like 15 km/h top speed of the French FCM Char 2C. Further, the role such a gigantic vehicle would have to perform in smashing enemy lines, positions, and formations, and high speeds would not be needed anyway. It could not go so fast as to outstrip accompanying and supporting vehicles and troops anyway.

Unlike the FCM Char 2C, Grote’s Fortress tank concept would not use multiple small road wheels but would, instead, use several (the exact number varies in the artist’s impressions) very large diameter (~2 – 3 m) double road wheels per track section. Each of these sets of wheels was mounted into a bogie and that bogie was sprung by means of hydraulic cylinders with a compensator of some type. Steering would be produced by simply braking one side of the tank.

On the matter of immobility, Burstyn was simply incorrect and working on an incorrect premise. He was not, however, wrong in his critique of the military utility of the vehicle, but Grote would have a long way to go before he could prove or promote his ideas again.

Conclusion

The 1933 concept was the culmination of tank work in the Soviet Union, where the tank had got bigger and bigger to accommodate more and more armor and firepower and the larger and larger engines needed to propel the machine. Trying to achieve the goals of heavy armor impervious to enemy fire, heavy armament, and high mobility seem impossible at first glance, especially given the inherent constraints on the size of a vehicle. As Grote would find, the only way to achieve everything he wanted was to step out of the physical limits imposed by things outside of tank design, such as road widths, bridging, and rail gauges. Once those limits were exceeded even slightly, there was suddenly no real limit on the size of the machine and he could start with huge amounts of firepower and massive sections of armor. In doing so, he also would need a means of propulsion which was not available to him at the time. The ‘1,000 tonnes’ was probably as a symbolic weight that might grab the attention or funding which an ‘872 tonne’ design might not, but Grote had embarked on a slippery slope with no limits imposed. The end result was a gargantuan machine which, whether or not it would even move, was irrelevant to what practical use it could possibly have had.

Untethered from the reality, limits on size the machine had grown perhaps way beyond what he had wanted, to a vehicle of huge proportions with a ludicrous array of armament. Grote’s design, quite rightly, was rejected by the Soviets, for whom a simpler and more conventional machine, well armored and armed, would find favor well after the T-35A.

It is perhaps ironic that the lessons learned by the Soviets from this German flight of fancy had to be relearned by the Germans a few years later. Grote, in fact, went on to further refine his ideas. During that development, the dimensions were still gargantuan for a tracked armored fighting vehicle, but the design did at least get a little less ridiculous as it went on, at least in terms of fewer turrets. The weight and armament of those designs, however, remained excessively large and they were equally unsuccessful.

Sources

Pearce, W. (2017). Mercedes-Benz 500 Series Diesel Marine Engines.

Pearce, W. (2017). MAN Double-Acting Diesel Marine Engines.

Frohlich, M. (2016). Uberschwere Panzerprojekte. Motorbuch Verlag, Germany.

CIOS report XXVI-13. Reich Ministry or Armaments and War Production. Section 16: Interview with Speer and Saur.

German Patent DE385516, Im Zweitakt arbeitende Verbrennungskraftmaschine, filed 25th April 1920, granted 24th November 1923.

German Patent DE370179, Verbrennungskraftmaschine, filed 25th April 1920, granted 27th February 1923.

German Patent DE344184, Zweitaktverpuffungsmotor mit Kolbenaufsatz, filed 4th June 1920, granted 21st November 1921.

German Patent DE370180, Verfahren fuer Gleichdruckmotoren, filed 26th October 1920, granted 27th February 1923.

German Patent DE370178, Verbrennungskraftmaschine, filed 7th January 1921, granted 27th February 1923.

German Patent DE373330, Schwinglagerung fuer Kolbenbolzen, filed 5th May 1922, granted 10th April 1923.

German Patent DE391884, Vorrichtung zur zentralen Schmierung von Maschinenteilen an Kraftmaschinen, filed 18th June 1922, granted 12th March 1924.

German Patent DE741751, Stopfbuechsenlose Druckmittelueberleitung von einem feststehenden in einen umlaufenden Teil, filed 6th January 1935, granted 17th November 1943.

German Patent DE636428, Stuetzrollenanordnung an Gleiskettenfahrzeugen, filed 6th January 1935, granted 8th October 1936.

German Patent DE686130, Geschwindigkeitswechselgetriebe, filed 6th January 1935, granted 3rd January 1940.

German Patent DE710437, Stopfbuechsenlose Druckmittelueberleitung von einem feststehenden in einen umlaufenden Teil, field 6th January 1935, granted 13th September 1941.

German Patent DE651648, Gleiskette mit Zugketten und einzelnen Metallgliedern, filed 6th January 1935, granted 16th October 1937.

British Patent GB457908, Improvements in and relating to Change-Speed Gears, filed 5th February 1936, granted 8th December 1936

US Patent US2169639, Clutch mechanism for change-speed gears, filed 20th May 1936, granted 5th January 1935

German Patent DE632293, Gleiskettenfahrzeug, field 11th June 1936, granted 6th July 1936.

French Patent FR817411, Dispositif de transmission d’un fluide sous pression, filed 5th February 1937, granted 2nd September 1937

German Patent DE698945, Kugelgelenkige Verbindung zweier mit gleicher Winkelgeschwindigkeit umlaufender Wellen mittels in Gehaeusen der Wellen laengs verschiebbarer Gelenkbolzen, filed 31st March 1937, granted 20th November 1940.

German Patent DE159183, Druckmittelüberleitung von einem feststehenden in einen umlaufenden Teil, field 14th March 1938, granted 25th June 1940.

German Patent DE159429, Druckmittelüberleitung zwischen zwei gegeneinander umlaufenden Systemen, filed 14th May 1938, granted 26th August 1940.

Belgian Patent BE502775, Einrichtung zur Befestigung eines Bolzens in einem Werkstueck, filed 25th April 1950, granted 15th May 1951.

German Patent DE842728, Einrichtung zur Befestigung eines Bolzens in einem Werkstueck, filed 28th April 1950, granted 30th June 1952.

Navweaps.com 28cm/52 (11”) SK C/28

Navweaps.com 28cm/54.5 (11”) SK C/34

MKB Ørlandet

Grote’s 1,000 tonne ‘Festungs Panzer’ concept, March 1933 specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 34 m Long x 10 m Wide x 11 m High |

| Total weight, battle ready | 1,000 tonnes |

| Crew | 40 |

| Propulsion | 12 x 2,000 hp |

| Speed (road) | 60 km/h desired |

| Armament | 7 turrets; 1 x twin 305 mm, 2 x twin 152 mm, 2 x twin 76 mm, 2 x 45 mm |

| Armor | 300 mm front, 250 mm sides, 100 mm roof, 60 mm floor |

| For information about abbreviations check the Lexical Index | |

8 replies on “Grote’s 1,000 tonne Festungs Panzer ‘Fortress Tank’”

Hard to imagine that Grote was ever serious with such a design. A tank of this scale would be impossible to transport and have fuel consumption so egregious that it wouldn’t even be funny, to name a few flaws. To think that this school of thought would continue for at least another ten years of German tank development, with no lessons learned…

“Vladimir Lenin” a.k.a. VL, P.1000 (in several variants), Ansaldo GL-203 – many projects of Interbellum period and early-WWII were seriously planned. Hardly one was ever realised, though.

This is often called “TG-V” or “TG-5”, does it somehow relate to real history?

If you take the dimensions given, the area of the armour (sides x 2, front, rear, top deck and belly) and multiply by thickness, then multiply by density of steel, the hull alone is around 1400 tons, without the turrets, suspension or drivetrain. Surely Grote would have figured this out. The other odd thing is the hull volume works out to be about 2000 cubic meters, so it would probably float.

We’ve once tried to calculate actual Ratte’s armor. It is either 50 mm around or 200 mm in front and 35 mm in other areas (with the same mass). I think this project must be someting alike.

Never knew about the TG tank. I continue to learn new things with every article!

Is the side-view drawing in scale?

Warhammer 40000’s Leviathan Command Vehicle has strong references from this.